Emory celebrates 25 years of expanding compassion and ethics through science

In partnership with the Dalai Lama, the Compassion Center’s three main programs — the Emory-Tibet Science Initiative; Cognitively Based Compassion Training; and Social, Emotional and Ethical Learning — are working to make the world a better place.

A name like the Center for Contemplative Science and Compassion-Based Ethics (CCSCBE) carries gravitas all on its own. And when that center is born out of a partnership between a leading academic institution and His Holiness the Dalai Lama, the impetus is even higher.

But for the Emory University faculty and staff involved with the Compassion Center, as it’s often called, the blend of ethics, compassion and science has been a driving force for the past 25 years and shows no sign of letting up soon.

What began as the brainchild of Geshe Lobsang Tenzin Negi and Robert Paul was formalized as the Emory-Tibet Partnership in 1998 and renewed Monday at the beginning of Tibet Week.

Celebrating 25 years, the renewal of the partnership between Emory University and the Drepung Loseling Monastery included senior leadership from the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, Institute of Buddhist Dialects, and Emory University leaders President Gregory L. Fenves, Provost Ravi V. Bellamkonda and Emory College Dean Barbara Krauthamer who reviewed the Memorandum of Understanding, signed in 1998 in the presence of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, with the current abbot of Drepung Loseling.

Negi had trained as a Tibetan monk at The Institute of Buddhist Dialectics in Dharamsala, India, before receiving his Geshe Lharampa degree — the highest academic degree granted in the Buddhist Geluk tradition — from Drepung Loseling Monastery in south India in 1994.

In 1991, when Negi was sent to Georgia to develop a meditation center, the Dalai Lama advised him to study Western philosophy and the science of the mind. Negi began looking into graduate opportunities at Emory, where he found Paul, a scholar who had deep knowledge of the rich Tibetan contemplative education system and who became his mentor. Negi was offered a scholarship and began studying at Emory.

“What led me to pursue this degree is that the Tibetan Buddhist tradition has a rich understanding of mind and emotions and how they contribute to our well-being,” says Negi. “But I wanted to study what modern science was demonstrating in that realm and to draw insights from each tradition.”

Paul and Negi continued to work together, discussing the possibility of building a stronger relationship between Emory and Negi’s alma mater, Drepung Loseling Monastery in India.

Gary Hauk, Emory University historian emeritus, had similar thoughts and was instrumental in facilitating conversations among university leadership about this possibility.

As the university secretary at the time, Hauk was involved in planning a visit by the Dalai Lama to Emory in 1995. During that visit, a delegation from Emory and Drepung Loseling in Atlanta presented His Holiness with the idea of creating a partnership between Emory and Drepung Loseling Monastery in India.

“His Holiness told us to start small and see where it goes,” Hauk says, “which led to further conversations and the eventual signing of the Emory-Tibet Partnership agreement in 1998.”

A few years later, Hauk asked Negi, who was completing his doctoral dissertation, if it would be possible to bring the Dalai Lama to campus as the university’s 1998 Commencement speaker. Negi said yes — and set about initiating a collaborative relationship.

Building a foundation

The initiative did, indeed, start small.

Negi describes it as a very humble beginning, with a group of faculty who shared the vision of His Holiness the Dalai Lama.

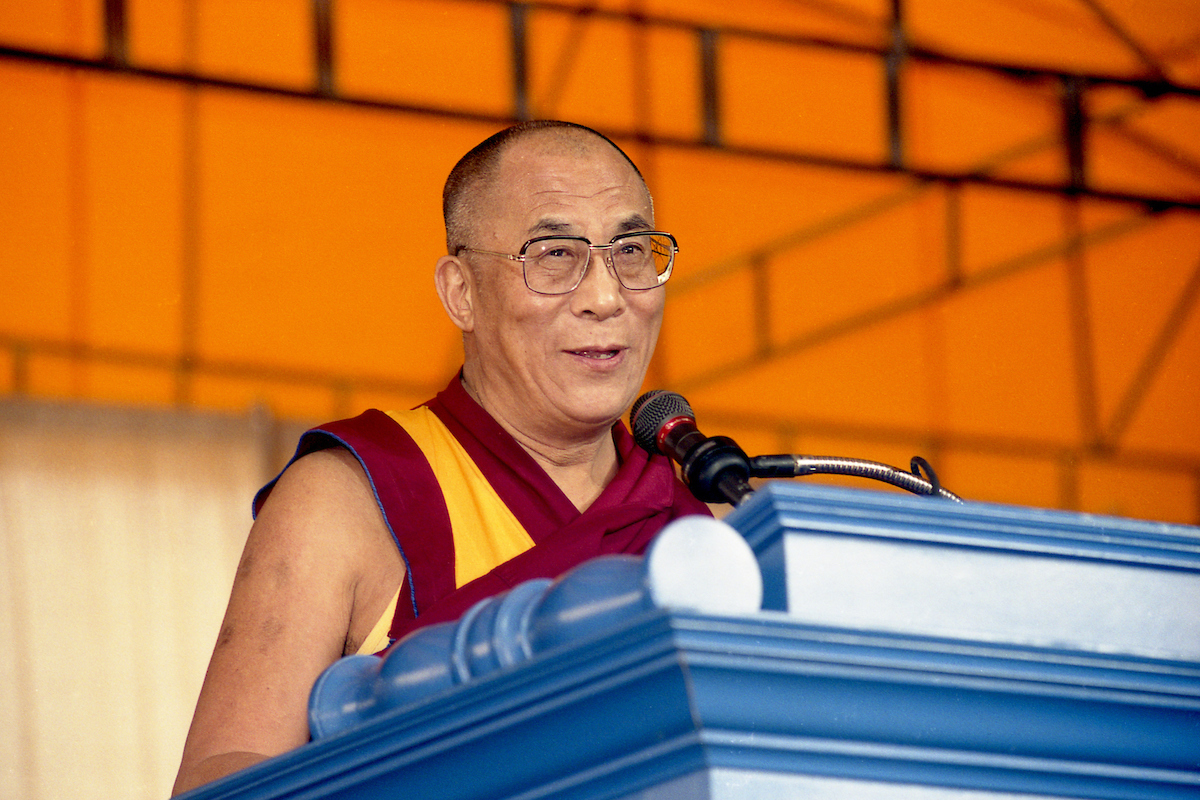

When the Dalai Lama delivered the 1998 Commencement Address, he also received an honorary Doctorate of Divinity degree and, crucially, inaugurated the Emory-Tibet Partnership.

In 2007, His Holiness the Dalai Lama accepted the invitation to join Emory’s faculty as a Presidential Distinguished Professor — the first and only time His Holiness has accepted an appointment with a Western university.

From 1998 onwards, the partnership focused on bringing Tibetan scholars to lecture at Emory and on sending Emory students to Tibetan communities in India via study-abroad programs.

But in 2006, the Dalai Lama proposed sending Emory scholars to teach sciences to monks and nuns in monastic institutions.

“The Dalai Lama has always been really interested in science and he felt it was good for all kinds of reasons that science should be introduced in the Tibetan monastic education,” Paul says of the program.

“The response of Emory faculty members to that idea was enormous,” says Hauk. “Many scientists in biology, neuroscience, anthropology, physics and more had attended some of the events surrounding the Dalai Lama’s previous visits and were captivated by his message and the prospect of doing something unique and important around education in science.”

In 2007, a cohort of faculty members started developing a science curriculum for the Emory-Tibet Science Initiative (ETSI), which eventually got modified into the current six-year curriculum that is now implemented in nine monasteries and three nunneries.

Watch this video celebrating 25 years of the Emory Compassion Center, and see photos from all three of the center's programs.

What’s in a name?

In 25 years, the Emory-Tibet Partnership has changed and grown — and so has the name.

The CBCT (Cognitively Based Compassion Training) protocol was developed in 2004 and the first research studies with Emory first-year students followed in 2005 Negi developed CBCT to help students reduce stress, anxiety and depression and as a way to advance the science of compassion.

The success of CBCT ultimately ushered in SEE Learning (Social, Emotional and Ethical Learning), which has engaged K-12 educators across the globe.

“It’s a unique focus that brings two different practices together,” says Negi. “It draws from both the ancient contemplative tradition but also from the emerging scientific research. One of the original visions of the partnership is bridging two worlds for one common humanity, and that’s what we’re working toward.”

Two of the three main programs aim to advance an ethical education by way of promoting compassion and other basic human values, all while being grounded in contemplative science. In light of that, the Emory Tibet Partnership was renamed the Center for Contemplative Science and Compassion-Based Ethics in 2017 — often shortened to the Emory Compassion Center.

Across the three core programs, the CCSCBE has 30 full-time staff members and programs implemented in more than 40 countries. Negi has served as director of the CCSCBE since he cofounded it in 1998 alongside Paul. Now, Paul is the Charles Howard Candler Professor of Anthropology and Interdisciplinary Studies and director of undergraduate studies and undergraduate research in the Department of Anthropology.

“I don’t think any of us would have imagined that this is what was awaiting us down the road,” says Hauk.

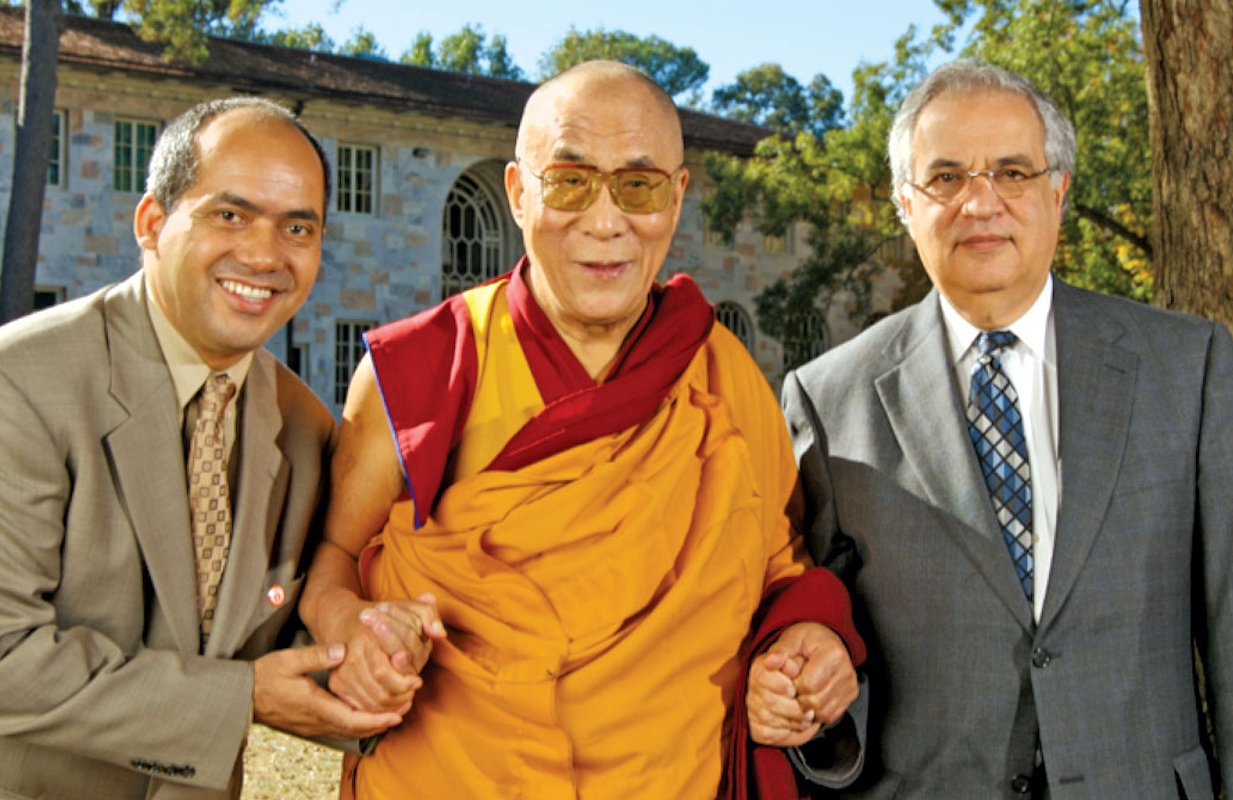

Gary Hauk (right) was also integral in the Dalai Lama’s 2013 visit to campus.

Creating three programs

The Compassion Center constantly has multiple projects happening in each program. A handful of individuals must know what’s going on in all three at any given time. One, of course, is Negi.

Carol Beck, associate director of operations and communications for the CCSCBE, is another.

“All of our programs are research-based,” Beck says. “Our programs are big undertakings, but it’s what we do, and we want it backed up by evidence.”

While everyone involved in the Compassion Center can offer plenty of anecdotal evidence of the differences these programs have made in their own lives or the lives of others, that’s not always enough to convince institutions like schools or hospitals to bring CBCT or SEE Learning to their staff. But hard evidence just might.

In fact, that’s what drove Joni Winston to begin donating to CCSCBE 20 years ago. She originally contributed to the Emory-Tibet Science Initiative, thanks to her own interest in meditation and attending one of the Dalai Lama’s visits.

“I became a donor because I really saw value in the work. The people at Emory were studying the benefits of meditation and teaching science to the monks and students in monastic institutions,” Winston says.

Winston was also interested in ways to bring emotional regulation and cooperative work skills into the classrooms of younger children. “By supporting Emory, a venerable institution with renowned and accomplished professors and scholars, that’s an institution that can cause change much more easily than I can alone,” she says.

The ETSI was founded with a vision to create a comprehensive and sustainable science education program for Tibetan Buddhist monastic universities. This unique education endeavor brings together the strengths of the Western and Tibetan Buddhist traditions.

Tsondue Samphel, senior translator/interpreter, exemplifies this bridge. Samphel was the first student selected from The Institute of Buddhist Dialectics, India, to study at Emory. He majored in physics from 2002-06 and considered graduate school when completing his bachelor's degree.

When Negi invited Samphel to join the ETSI project in its early stages as a translator and as someone familiar with both monastic culture and Western education institutions, he jumped at the opportunity.

“I saw an immense value in teaching science to the monastics,” says Samphel of that conversation. “Although science and religion may be viewed as antagonistic in some senses, I saw science as an area that explores the physical world and universe through rigorous investigation and observation. Whatever science discovers has to be a feature of the universe. And if that’s the case, the monastics should know about it.”

ETSI offers four main subjects — cosmology and physics, life science and biology, neuroscience, and the philosophy of science — to the monastic students in its six-year science curriculum. Its dedicated faculty develops primers and other textual materials for each of the four units in English, which Samphel and his colleagues translate into Tibetan. Each translator chooses a field to focus on and translates any necessary materials, from slide decks to textbooks.

Because science is relatively new to the Tibetan language, a lot of the translating energy goes into creating and building scientific lexicons. It also led Samphel and his colleagues to collaboratively create a standardized scientific vocabulary in Tibetan that is now used in the ETSI’s textbooks and other publications.

“If we couldn’t find an equivalent word to use, we would look at the etymology and origin of the English word and often render that Latin or Greek root word into Tibetan, or add a particle here or there to indicate the specific meaning of the word,” Samphel says.

An essential component of this creative process is the annual translation conference organized by ETSI during which translators, language experts and science educators from different fields attend a week-long International Conference of Standardizing Scientific Terms in Tibetan. As a group, attendees go through the new scientific words in Tibetan created by ETSI translators, discussing the accuracy, elegance and brevity of each new term and finalize them. The finalized words are then used in subsequent translations to enhance access for Tibetan monastic communities and Tibetans at large.

Since 2009, these conferences have contributed to the establishment of more than 7,237 scientific terms in the Tibetan language.

“But the larger goal of ETSI,” says Tsetan Dolkar, associate director of ETSI, “is to cultivate Buddhist contemplative scholars who are well-qualified to engage in scientific research, who can collaborate with scientists to advance contemplative science and develop new understanding of human conditions for the benefit of the entire humanity.” This larger vision of the program aligns perfectly with the Center’s other works.

Emory is known for its research prowess — and that’s exactly what it brought to the table to further compassion in the world.

When Negi finished his doctoral program as a student, he was hired to teach in Emory’s Department of Religion. He offered a class called “Tibetan Buddhism: The Psychology of Enlightenment,” which presented some mediation models with underlying psychology principles. That class, and conversations with students, led Negi to develop CBCT.

To create the program, Negi partnered with renowned scientist Charles Raison, MD, who, at the time was the director of the Mind-Body Program at Emory School of Medicine’s Department of Psychiatry.

Raison’s research focused on the mind-body connection and mental health struggles, such as depression. Negi and Raison teamed up to conduct research, developed a protocol in the form of a class and offered the course to first-year college students.

“The results were promising as we compared students who put in time meditating against students who attended class but did not meditate outside of it. When compared to the control group, practicing students demonstrated a significant difference in terms of their inflammation in the body as well as how fast the cortisol drops after exposure to stressful tasks, and showed improvement on the subjective, self-reported scales for depression,” Negi says.

While the scales are self-reported and subjective, the measurements of inflammation and cortisol are quantitative data points, offering a more holistic view of the internal changes.

The study started in 2005, and CBCT has since been offered in many different communities, including across nine different countries and by more than 150 certified teachers.

“Our initial focus was more on research and understanding the science behind compassion,” says Negi, “I think in many ways, Emory’s compassion program has been one of the pioneer programs in doing research based on compassion protocols.”

Next up? Scaling the program.

That’s one of the main focuses of Timothy Harrison, associate director for CBCT. A 10-year initiative to scale CBCT was funded in 2021 by the Rob and Melani Walton Foundation, along with a number of other generous donors. In late 2024, Phase I will conclude with the international launch of The Compassion Shift, an initiative that includes an interactive and multilingual app to make CBCT readily adoptable across the world. The Compassion Shift is the center’s ambitious education initiative aimed at both adults and children.

While SEE Learning ultimately carries the same goals as CBCT, the program is specifically designed for younger minds in K-12 classrooms. The SEE Learning started in 2015 before being globally launched in 2019 at an event with the Dalai Lama.

But long before that, Brendan Ozawa-de Silva, associate teaching professor at the CCSCBE, began visiting schools in the Atlanta area to teach CBCT to young kids in 2009.

“I spent several months observing the schools and then three months teaching in them,” Ozawa-de Silva says. “That work continued for about five years, and we ran a few studies exploring if you can teach complicated forms of compassion training to very young kids.”

The most popular hypothesis was “no” — but the study results demonstrated that not only was it possible for the kids to understand it, but they seemed to like it.

In fact, one of the six-year-old girls in that classroom is now a student at Emory who is double majoring in religion and philosophy. In 2009, she would tell Ozawa-de Silva how meditation helped her when she was stressed before ballet competitions. By high school, she was living in New York City and planning to be a full-time ballerina. Then COVID-19 hit and she pivoted her plans.

“It’s rare to have examples of kids that were exposed to this training at six years old and then come back and tell us how impactful it was,” Ozawa-de Silva, who is now her academic advisor, says. “Those early experiences in 2009 really showed us that you could teach kids this pretty complex form of perspective taking and systems thinking and how to deal with emotions.”

In 2010, Ozawa-de Silva presented this work to the Dalai Lama, who said, “It feels like the night is ending and the sun is dawning on a new world.”

In 2015, the Dalai Lama asked Negi to develop a framework and sample curricula for what he called Secular Ethics, now known as SEE Learning. Negi led a team, including Ozawa-de Silva, in developing the framework and later charged Ozawa-de Silva to lead the effort to develop a set of curricula for K-12. In 2019, SEE Learning was officially launched in India in the presence of His Holiness.

Now, SEE Learning is conducting a multi-site study across 10 locations to get better data on the impact of the program in varied settings and with varied audiences.

Associate Director for SEE Learning, Ryder Delaloye, explains that many schools respond to SEE Learning with awe and appreciation, and are excited to learn that values such as compassion, resilience and awareness can be framed as enduring capabilities. Students of all ages have expressed program benefits, from becoming more aware of their own emotions to helping others work through tough times.

Delaloye is most proud of the center’s work to further awareness and compassion in the world. “The vision of the center is ‘A compassionate and ethical world for all.’ We are working to remove barriers and to expand access to our programs to people, schools and organizations around the world,” he says. “I am grateful to directly support this effort and privileged to be a part of a global compassion revolution.”

A center rooted in Atlanta to reach the world

Over the years, some people have been surprised that this center is rooted in the South. But to Mark Hughes, lead director of development for the CCSCBE, it makes perfect sense.

“If you think about the work, especially the social justice work we’re doing through the center, it really weaves in nicely with the history of Atlanta and the fabric of advocacy and equity that has been part of this city,” Hughes says.

“We’ve come a long way,” Negi says, “but the way I see it is that it’s now well established and it’s putting branches out and bearing flowers and fruit. The potential for the program to contribute to the knowledge and well-being of our community and the world at large is tremendous.”

Harrison echoes the potential for change, explaining that to create a better world will require changing external structural realities as well as the inner lives of individuals.

“The work of the center is not about inventing something new. It’s about tapping into the capability for a more inclusive compassion that we all have,” he says. “The promise of the work is to share these practices and make them more available so that all of us can be our best selves in the future.”

Photos by Emory Photo/Video and provided by the Center for Contemplative Science and Compassion-Based Ethics

Celebrate 25 years of Center for Contemplative Science and Compassion-Based Ethics

For members of the Emory and Atlanta communities — and beyond — who want to find out more about the Compassion Center, Tibet Week is the perfect opportunity to do so. Events for the Silver Jubilee started Monday, Nov. 6, and continue throughout the week with opportunities to watch the Mandala Sand Painting, join a compassion meditation, attend a seminar and more. Many events are available in person and online.

Resources:

Center for Contemplative Science and Compassion-Based Ethics

The Emory-Tibet Science Initiative

Student Flourishing Initiative

Related Stories:

Celebrate Tibet Week at Emory with events across campus

Conference with the Dalai Lama highlights Emory Compassion Center’s work

Emory's Compassion-Centered Spiritual Health derived from ancient Tibetan traditions

Summer, service & social justice