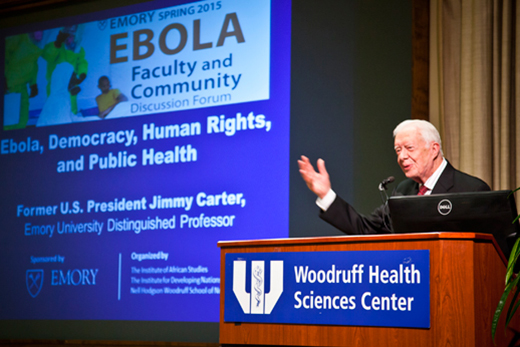

If people don't trust their government because of a history of human rights violations, they also won't trust it for public health information, former U.S. President Jimmy Carter noted in a recent address to Emory's Ebola Faculty and Community Discussion Forum.

Carter, the nation's 39th president and University Distinguished Professor at Emory, is founder of The Carter Center, an Atlanta-based nonprofit dedicated to "waging peace, fighting disease [and] building hope." During the April 9 speech, he discussed the importance of earning public trust and how The Carter Center's 25-year presence in Africa shaped its response to the Ebola crisis.

Carter's address was the sixth event in the Forum series, which provides opportunities to examine Ebola virus disease from interdisciplinary perspectives and is organized by Emory's Institute for Developing Nations, Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing and Institute of African Studies.

The start of the Ebola outbreak "was noticed for the first time in March 2014 and it was basically ignored by the World Health Organization, by the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention], and by the organized group of people who were dealing with public health," Carter said.

In the past, when a small outbreak of Ebola took place, health officials could go in and contain it so it wouldn't spread, he said. "This time, it developed in Guinea and Sierra Leone, but most of the cases were in Liberia. And they didn't know what to do."

At the time of the Ebola outbreak last year, The Carter Center had three ongoing programs in Liberia, one of which was training nurses in responding to mental health issues.

"In March 2014, when the Ebola crisis emerged, the program leaders decided to let the trained nurses concentrate on the disease, if they wanted to. It was natural that we give our attention to that problem of Ebola in Liberia," Carter said, adding, "We had to get permission from donors to shift emphasis during the crisis to Ebola."

"It was not until August after the outbreak in March that this was declared a crisis or emergency by WHO and by CDC," he said.

Carter said that health officials initially claimed in interviews that the Ebola outbreak, like previous outbreaks, could be controlled. "But it got worse and worse and became a horrible debacle in those three countries," he said.

Earning the public's trust

The Carter Center responded to the crisis with public service announcements broadcast on the radio throughout Liberia. The PSAs were successful, the former president said, because people trusted the information.

Liberia's 15-year civil war and history of oppression and human rights violations had created a massive distrust of the central government, despite its improved rights record and commitment to democratic governance, he explained.

When the Ebola crisis broke out, Carter said, "it was obvious to us" that citizens didn't believe the government's information and instructions about the disease.

"I think that's what you have to have — the trust of the people," he said. "We never became experts on Ebola, we never treated anyone for Ebola, but people believed our radio commercials. We got our information on Ebola from WHO and the CDC."

Carter noted that the epidemic is finally waning, and stressed that the lessons learned from fighting it must help inform the response to future crises.

"So now I'm happy to announce, which you already know, there are no detected cases of Ebola left in Liberia. There are a few cases in other countries, in Guinea and Sierra Leone," he said. "So I would say that The Carter Center and Emory University played some role in making sure that it was addressed in Liberia in an effective fashion."

Neglected diseases, neglected places

In response to a question about how the Ebola crisis was handled in this country, Carter said, "We handled it very poorly here in the United States, except at Emory.

"I think that the worse thing we did in the Ebola crisis was to mislead the people about the efficacy of getting rid of it, because based on past experiences, before people became so mobile, if you found Ebola in a little village, you could go into that village and the people rarely moved to another place," he said.

"But nowadays, people are much more mobile and I think that was a very serious problem. And we didn't understand the culture of the people in those countries either."

Carter also observed, "Neglected tropical diseases occur in neglected places."

In combatting and preventing these diseases, he noted that illiteracy makes the education part extremely important. The lack of media is also problematic, he said, although radio and cellphones are pretty prevalent now.

"Education and information and trust for the ones giving out the information are the key points in getting ready for the next problem," he said.

Carter said he believes "Ebola might be a kind of an awakening factor."

"I don't think there is any doubt that the CDC, the government of the United States, the European countries, the United Nations agencies, including WHO, will be much more committed now to making sure that in the future, ministries of health get more aid and more advice and more training and money than they have in the past," he said.