Ruby Lal didn’t plan to write a book for young people. But sometimes, a work finds its author, rather than the other way around.

Lal, Emory professor of Middle Eastern and South Asian Studies, had already written about Nur Jahan, the 17th-century Mughal ruler, in her book “Empress: The Astonishing Reign of Nur Jahan.”

The book explored how the brilliant, compassionate sovereign led a life of intrigue and defied the odds to become the only woman to serve as empress of the Mughal empire between 1611 and 1627 — a long period in the history of an empire that reigned over much of present-day north, west and east India from 1526-1707.

But as Lal researched, wrote and promoted that work, everyone — from readers, to students, to her own nieces — kept asking the same question: When would she write a version for young adults?

By the time she met Molly Crabapple, a New York artist and illustrator who admired Mughal art and was fascinated by Lal’s research, the project felt nearly fated. “It’s almost as if I was just connecting the dots,” says Lal.

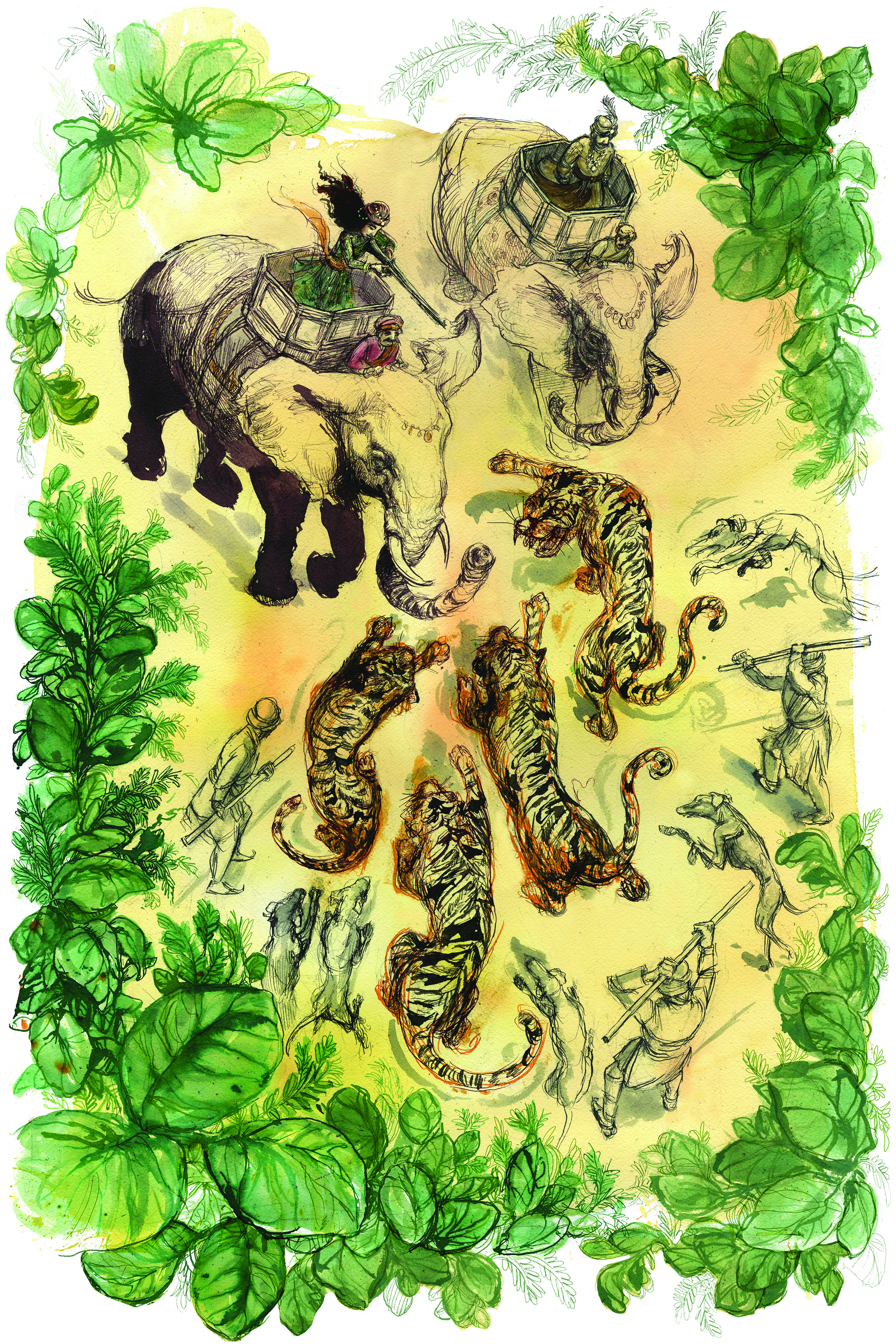

Paintings by Molly Crabapple work in concert with Lal’s text to bring the story vividly to life. “In the end,” says Lal, "the words and images are speaking to each other.”

“Tiger Slayer: The Extraordinary Story of Nur Jahan, Empress of India,” brings together Crabapple’s lavish watercolor illustrations with Lal’s text to tell Jahan’s story to teen audiences. The book is a 2025 Junior Library Guild selection. Booklist calls it “deeply satisfying,” while Kirkus says it “sets a new standard for works celebrating overlooked historical figures.”

“Tiger Slayer” is the latest in a series of works in which Lal has sought to spotlight the stories of historical individuals shuffled to the margins.

“Empress” was a Los Angeles Times Book Prize finalist in history and won the Georgia Author of the Year Award for biography in 2019. Her book “Vagabond Princess: The Great Adventures of Gulbadan,” was shortlisted for the James Tait Black Prize in biography, longlisted for the Cundill History Prize and was a finalist for the 2025 Georgia Author of the Year Awards in the category of biography.

Clues of a powerful reign

It was widely known that, after becoming Emperor Jahangir’s 20th and final wife in 1611, Nur Jahan rose in authority to join his inner council of advisors before becoming his co-sovereign.

But the few essays and scholarly articles written about her, while sometimes highlighting her bravery and power, tend to focus on her passionate romance with Jahangir. And they end with their marriage, claiming it as a vital explanation for Nur’s rise.

As Lal told an audience in her 2025 John F. Morgan, Sr. Distinguished Faculty Lecture, “her reign was locked up in legends of irrational love, a besotted and drunken emperor bewitched by a scheming woman. And thus, we knew her, but knew nothing about her.”

Lal scoured primary sources, including Mughal painting, poetry and architecture, as well as court chronicles and memoirs by Emperor Jahangir. She found more than 30 mentions of Nur Jahan’s hunting prowess, including of tigers.

“And here’s the thing about hunting,” says Lal. “Only kings hunted tigers, not ordinary people.”

Not only did slaying tigers symbolize the ultimate in authoritarian machismo; hunting trips allowed emperors to meet locals, gather intelligence and put a stop to local injustices. Nur Jahan did all these things.

Poets at the time celebrated her abilities as a slayer of tigers. A famous tale relates how, during one hunt, she killed four tigers with six rifle shots while seated on the back of an elephant. Another story describes how she killed a marauding tiger that was slaughtering people in a Benghal village.

A famous painting by court painter Abul Hasan tells us everything we need to know about the unique power and prowess of the Mughal empress. “Hasan was a great portrait maker,” says Lal, “but in this this one painting, he breaks from his own oeuvre to show Nur in action, loading a musket.”

A thrilling ascent to power

“Tiger Slayer” shares Nur Jahan’s story in rich detail, full of twists and turns.

Readers learn that by the time Nur arrived in Jahangir’s harem, she had already experienced a degree of drama rivaling the most thrilling of modern-day TV series.

Practiced in political survival and intrigue, Nur eventually made royal decrees of her own, even greeting her people from the balcony of the royal palace.

During a first marriage to a Mughal courtier that began when she was 17, Nur was posted along with her husband in Benghal, which Lal notes was like the “wild west” of the Mughal dynasty.

“She actually had to be really independent while he was away, working,” Lal says. “So, she had experienced all sorts of political tension, and the murder of her husband by the time she was 30.”

That’s when she was brought to the harem of Emperor Jahangir: the man who, according to legend, had her husband killed.

But history shows the truth to be a little more complicated, notes Lal. Nur was the daughter of Jahangir’s prime minister. Families of all employees were under the care of the emperor. And Jangahir’s marriage to Nur demonstrated that care.

Practiced in political survival and intrigue, Nur was eventually making royal decrees of her own. In a climactic scene, she greets her people from the balcony of the royal palace, a Hindu practice first instituted by her husband’s father.

As Lal writes: “Now Nur appeared where no other Mughal queen had before, or would after. The empress showed herself on a balcony, at a distance, like a goddess.”

She was an empress now, in full command of her power.

Respecting her readers

From the start, Lal knew that “Tiger Slayer” would be more than a version of Jahan’s story simplified for young readers.

“I decided I was not going to tamp down the story,” she says. Instead, she shares its full drama in a way that’s accessible to teen readers, without sacrificing accuracy or detail.

Lal spent a lot of time discussing craft with experienced young adult, or YA, writers, including strategies for breaking down complex information.

In “Tiger Slayer,” sidebars serve as signposts, identifying key characters and historical events.

And paintings by Crabapple work in concert with Lal’s text to bring the story vividly to life.

An illustration of Nur’s first, fateful tiger hunt expresses the motion and excitement of the moment while accurately depicting everything from her style of dress to the manner in which she would have sat on the elephant’s saddle.

“We worked together very closely,” says Lal, “and in the end, the words and images are speaking to each other.

“I really think young people are looking for these different kinds of stories told with depth,” she adds, “stories that illustrate powerful women.”

Lal notes that Nur’s tale showcases the surprising forms power can take — benevolence, for one. “Nur was very compassionate. She gave huge donations to the poor, including dowries to 500 underprivileged girls.”

She even designed an inexpensive, fashionable wedding dress for those girls.

Acts like these demonstrate a “non-masculinist” model of power that we could learn from today, says Lal, adding, “I think the job of an historian is to bring to light what power looks like, right? And there is power in somebody protecting their subjects.”

The roots of a diverse culture

Lal finds great inspiration in the diversity of Mughal society.

An illustration of Nur’s first tiger hunt expresses the excitement of the moment while accurately depicting everything from her style of dress to the manner in which she would have sat on the elephant’s saddle.

Meanwhile, following Jahangir, many Mughal princes were sons of Rajput Hindu women. “And the emperors were really interested in the faith practices that surrounded them, from Hinduism to exchanges with Jesuit princes, to Jainism. This was a truly multi-denominational culture, and it showed: in their architecture, in all kinds of things.”

Today, India’s diverse culture bears the beauty and mark of that pluralistic influence, says Lal.

“If you look at Bombay, say, on the same street, you’ll see a mosque, a Sikh temple, a Jewish Temple, a Farsi temple — and the people who walk by bow in front of everything.”

She considers her work as an historian, drawing attention to historical details and their throughlines to the present, “the work of civilization.”

Next up, Lal will write a book about the Taj Majal — one of the seven wonders of the world — which was inspired by the marble mausoleum that Nur Jahan designed for her parents. She’s also planning a comprehensive history of the Mughal Empire.

“Teaching history is about continuing to share the rich and complex layers of the past, which is important to the making of future citizens,” she says. “That's what we do at Emory. And it’s what education in the humanities is really about: Who will be our future citizens?”

The inspiration goes both ways; Lal says she’s grateful to her students, from whom she continues to learn.

“I will always teach a freshman seminar,” she says. “I will do it every year, because you learn so much. I mean, I never would have written this book without the invitation of young people.”

All illustrations used with permission by artist, Molly Crabapple.