“Like a lot of girls raised in India, I grew up hearing a range of stories soaked in myth, history and legend. My mother was a fabulous storyteller, and I was besotted by what she related. Retrospectively, I realized that she was often telling me a lot about unique girls and women,” says Ruby Lal.

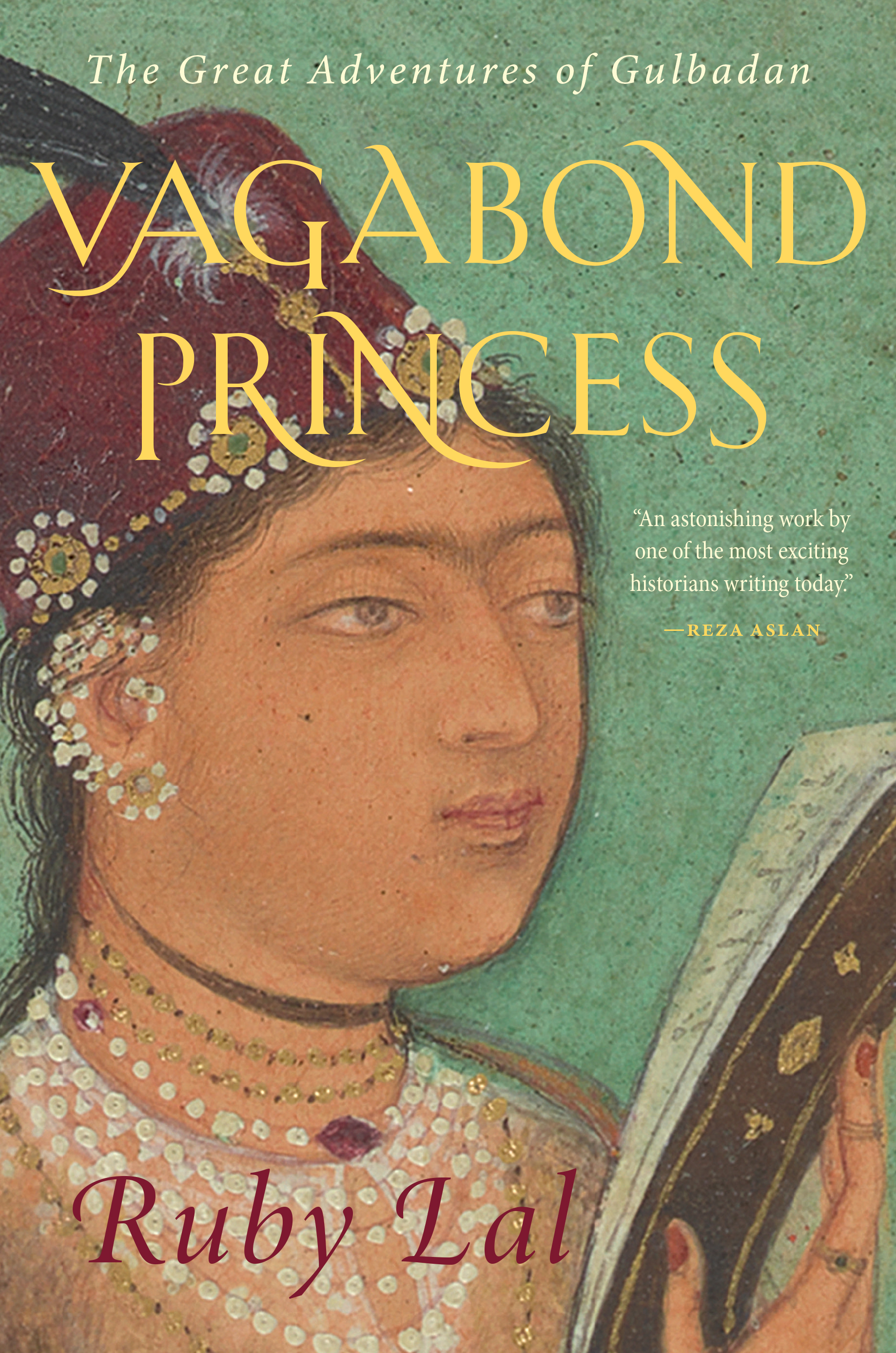

With the release of her new book, “Vagabond Princess: The Great Adventures of Gulbadan,” Lal provides the first biography of Princess Gulbadan of the Mughal court — a charismatic figure referenced in Lal’s books “Empress: The Astonishing Reign of Nur Jahan” (2018) and “Domesticity and Power in the Early Mughal World” (2005). “Empress” was an LA Times Book Prize Finalist in History, and Lal received the Georgia Author of the Year Award in Biography in 2019.

A professor in Emory’s Department of Middle Eastern and South Asian Studies, Lal studies colonial and precolonial South Asia; the Mughal, Ottoman and Safavid Empires; history of Islamic societies in the early-modern and modern world; and feminist theory and history as it relates to the archive.

The adventures of a princess and her biographer

Gulbadan, the central figure of “Vagabond Princess,” was asked to “write about the great men of the dynasty”; instead, “she produced an account of everything the women were up to.”

Who was this princess? Daughter of the first Mughal emperor, sister to the second and aunt to the third, Gulbadan was a dynamic figure and a trusted advisor to the empire. “Vagabond Princess” begins in Kabul. The Mughals moved often across long distances, living for extended periods in the open country in tents pitched in gardens and citadels.

But when Gulbadan was in her 50s, her nephew Akbar the Great established a walled harem in his capital, Fatehpur-Sikri, near Agra in an effort to showcase his authority. From behind these walls, the princess longed for the exuberant itinerant lifestyle she had long known.

And so, Gulbadan led her female companions across the seas to the Muslim holy cities. And, says Lal, “a veritable scandal erupted while she was in Arabia,” not to mention a dramatic shipwreck in the Red Sea.

Lal had been fascinated by Gulbadan since bringing her memoir to the attention of the scholarly world in “Domesticity and Power,” her first book. And Lal was not alone: readers, especially those in India, clamored to know more about her.

“Keeping Gulbadan in my sights for 20 years and now exploring her life extensively, I have enjoyed my own adventure, complete with surprising twists and turns,” Lal notes.

Professor Nadini Das, of the University of Oxford, commented: “Meticulous archival research combines with a strikingly imaginative evocation of the world inhabited by Mughal women in Ruby Lal’s writing. Whether set against the dust and grit of imperial caravans, salt-lashed sea voyages or the manicured precision of Mughal gardens, her vagabond princess, Gulbadan, surprises us at every turn.”

Since the book’s publication at the end of February, strong reviews appeared in Publishers Weekly, Kirkus Reviews, BBC, NPR, Vogue India and numerous literary magazines in the U.S., U.K. and India. Ms. Magazine named it among the Most Anticipated Feminist Books of 2024 and Five Books flagged it on a list of Nonfiction Books to Look Out for in Early 2024.

Finding the ‘indomitable’ women of history

During her days at University of Delhi — where she earned a master of arts and master of philosophy, before she went on to earn a doctorate at the University of Oxford — Lal was not afraid to go against the grain of Indian history students, most of whom specialize in modern history, the colonial period or the 1947 partition of India and Pakistan.

“I, on the other hand, was fascinated by the great Mughals of India,” says Lal of the empire that ruled the majority of northern India from the early 16th to mid-18th centuries and was perhaps best known for building the Taj Mahal.

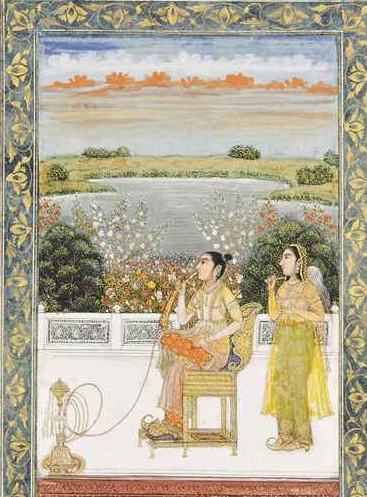

An illustration of the princess smoking a hookah. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

But not for long — not as Lal made her way in the scholarly world.

Lal won the Inlaks Shivdasani Foundation Scholarship which, along with the Rhodes, are two paths by which gifted Indian students earn a place at the University of Oxford. “That is where my story with Gulbadan began,” she notes.

In England, between 1996 and 2000, she consulted Gulbadan’s manuscript — the lone surviving copy — in the British Library. Gulbadan had been asked to write her memories of her forefathers as a contribution to the first official history commissioned by Emperor Akbar. He knew, says Lal, that “Gulbadan would be vital in recording the celebrated achievements of Mughal men.”

But the princess — a skilled prose writer in an era when most royal women wrote only poetry — had something else in mind. What resulted was “unparalleled in form and content, narrating jaw-dropping events of her own life, filled with quotidian, playful, daring and eccentric occurrences,” says Lal.

Her nephew, the emperor, was not pleased, which explains the survival of only one example of what ordinarily, as a royal text, would have merited careful preservation of multiple copies. Gulbadan dealt a blow to male-dominated chronicles. Lal shows the layers of action around the missing pages redacted by the royal historian who did not want the princess to have her say.

Annette Beveridge, who translated Gulbadan’s account into English in 1901, received an acceptance letter from her publisher pronouncing the memoir “a little history … it is but a little thing.”

Such a view has not been limited to the thinking of the Victorian era.

Who decides what history is?

Over the course of her career, Lal has dealt with what she calls the persistent “male disbelief” that dismisses, marginalizes and thereby erases women-oriented sources. Reanimating and reinstalling such sources — memoirs, poetry, art and architecture — and working through their histories of production “is the ground upon which feminist history has thrived since its earliest days,” says Lal. She has written about feminist practices in a recent article for Time magazine: “What a Mughal Princess Can Teach Us About Feminist History.”

Lal teaches courses such as Powerful Women in Global History and India’s Women: Leadership, Power and History.

One piece of advice she shares with Emory undergraduates is to “look where you don’t habitually look.” In any course Lal teaches, the philosophical underpinnings are “Who decides what history is? What constitutes evidence?” Lal says of her students, “They make vital links to contemporary forms of racism and sexism. Indeed, they brilliantly move the material forward, complicating it in instructive ways.”

In “Vagabond Princess,” Lal takes it upon herself to demonstrate what it is to “look where you don’t habitually look.”

To understand Gulbadan’s journey to the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, Lal found that Ottoman documents were rich in ways that Mughal documents were not — and that there was a reason why Mughal documents didn’t shine a light on Gulbadan’s years in western Arabia.

Ottoman Sultan Murad III was in charge of the holy cities at the time and had issued five eviction orders against the Mughal women, classifying their actions as “un-Islamic.” Housed in the National Archives in Turkey, the orders — which Lal carefully studied — were key to the story she tells of Gulbadan.

She also wanted to convey a deep understanding of what being in a desert land in the 16th century would be like: How did the women spend their time? Where did they live? What was “un-Islamic” about their actions? All this demanded studying the geography of the regions and learning all Lal could about the arrangements for traveling royal women.

“I ventured into new historiographies doing this work and trained myself in new fields, such as Ottoman western Arabia and the Red Sea region, in order to bring this story to light,” Lal observes.

‘Booking’ passage to richer worlds

“I was not as interested in settling what happened [the break in the memoir that occurs at folio 83] as I was in charting the drama that surrounds the void and learning everything the princess was doing. That, in itself, is a magical story,” says Lal.

In the last chapter, “The Books of Gulbadan,” Lal ponders Gulbadan’s memoir and the inspiration behind its unique form.

The wide world and its people were her books. Her knowledge germinated from gardens, tents, pavilions, caravans, ships, rivers, oceans, deserts, camels, mosques, water fountains, hills, mansions and the red sandstone harem… Women in history … were her books. Experience was her book. Crossing the Khyber Pass in a caravan at the age of six, being a young woman in exodus to Kabul and her time as a sagacious woman lodged in the harem: all informed her writing. Indoors and outdoors, upon the seas or on the land, her own body was her experience.