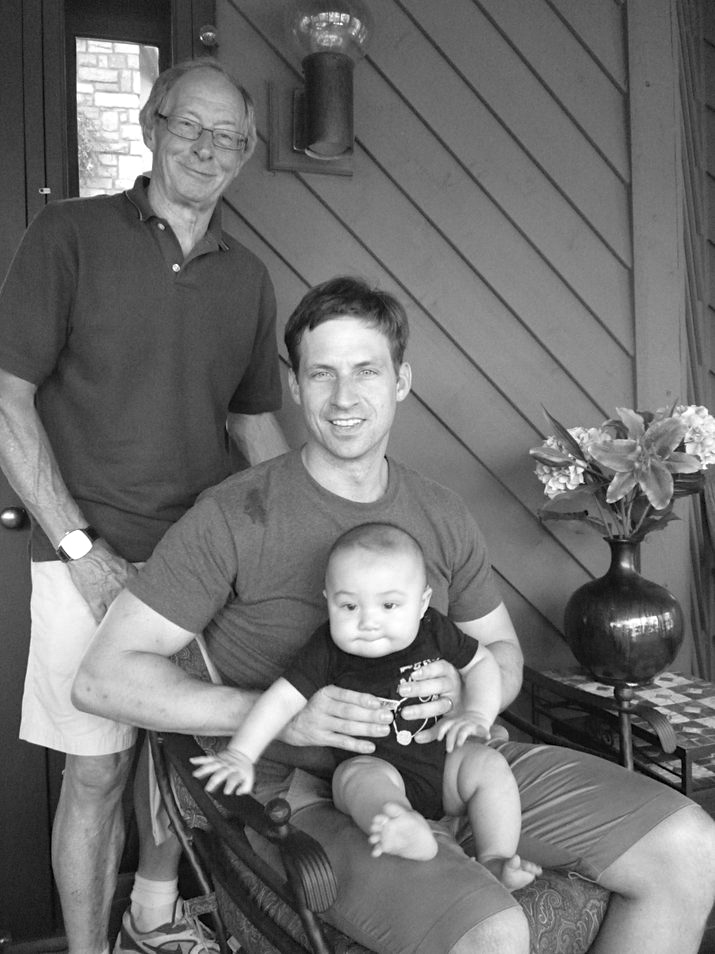

Shortly after becoming a first-time father in 2011, James Rilling holds his son, Toby, as his own father, Richard, stands behind him.

“He made me this tiny booklet of several pages and titled it, ‘What Daddy Likes,’” says Rilling, professor in Emory University’s Department of Psychology and Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. “Inside, he had drawn pictures. One page had a hamburger. Another one, a football. It was interesting to see what I like from his perspective. It’s super cute. I still have it.”

Toby, now 14, and daughter Mia, 8, help inspire Rilling’s pioneering research on dads.

His recently published book, “Father Nature: The Science of Paternal Potential,” sums up the evidence for why human males evolved the capacity to be involved caregivers, how that care benefits their children, and the circumstances in which it is more common.

There is no one-size-fits-all gift to please every dad this Father’s Day.

What holds more universal appeal is simply telling a father that his efforts are noticed and appreciated, Rilling says.

“A lot of times dads feel like, since motherhood is more challenging than fatherhood, they shouldn’t get much attention,” he says. “But one of the things I’ve learned from interviewing dads is that they find it really therapeutic when you ask them how they feel about the rewards and challenges of fatherhood.”

Rilling grew up in Wisconsin with three older brothers and a positively engaged father, Richard, who is now 85.

“I have a lot of great memories of him coaching us in sports,” Rilling recalls. “Also, playing football in the yard and basketball in the driveway. We had some epic games that I really enjoyed.”

Fathers often engage their children in rough-and-tumble play, which helps children learn to regulate their emotions, correctly read the emotions of others and interact more skillfully, Rilling notes.

James Rilling with his father, Richard, during a 1975 family trip to Niagara Falls.

He also appreciates his father’s gentle side.

“When I was four or five, we were playing in the surf of Nantucket Island,” Rilling says. “Huge waves were coming in and I got washed away by one of them. I was a quarter mile down the beach and my dad was panicking. He thought he’d lost me.”

His father soon came to the rescue.

“I had sand just everywhere and I had swallowed a lot of salt water,” Rilling says. “I felt really bad. My father took me to the bathroom and cleaned all the sand off me. On the ferry ride back to the mainland, he sat with me the whole time and put his arm around me. I could tell how bad he felt and how much he loved me.”

His father’s gift for patience also buoyed Rilling’s childhood.

He recalls fishing trips to lakes in northern Wisconsin when his father would take all four of his young sons out in a small boat. “My brothers and I would get our lines tangled and start fighting about how we were getting in each other’s way,” Rilling says.

“My dad would calmly attend to each one of us in turn: untangling a line, dealing with a snag. He never got upset. And he never did any fishing himself. All he cared about was making sure we all had fun. That really captures his character.”

Recent decades have brought a major shift in what fathers may think is expected of them.

“A lot of dads used to feel that their role was primarily to provide economically and not to provide as much warmth and nurturing,” Rilling says. “I think that’s changed a lot. My dad was a bit ahead of his time on that.”

He notes that research suggests that the most effective parenting style is authoritative — setting and enforcing appropriate limits — while also being warm and responsive to a child.

“Our influence as parents is not absolute,” Rilling adds. “There are many factors that affect how well our children do, including genetics, that we have no control over. There is emerging evidence that children vary in how readily they can be shaped by parenting. Parents don’t always have as much influence over their kids as they think they do. It depends on the child.”

Perhaps the most important message to dads, Rilling says, is to just keep trying their best while also giving themselves a break.