Peacemaker. Leader. Poet. Farmer. Engineer. Rock ‘n’ roll president. Steadfast partner. Beloved professor. Revered friend.

President Jimmy Carter was many things to many people throughout his life of service — at Emory, in Georgia, on the national stage and internationally.

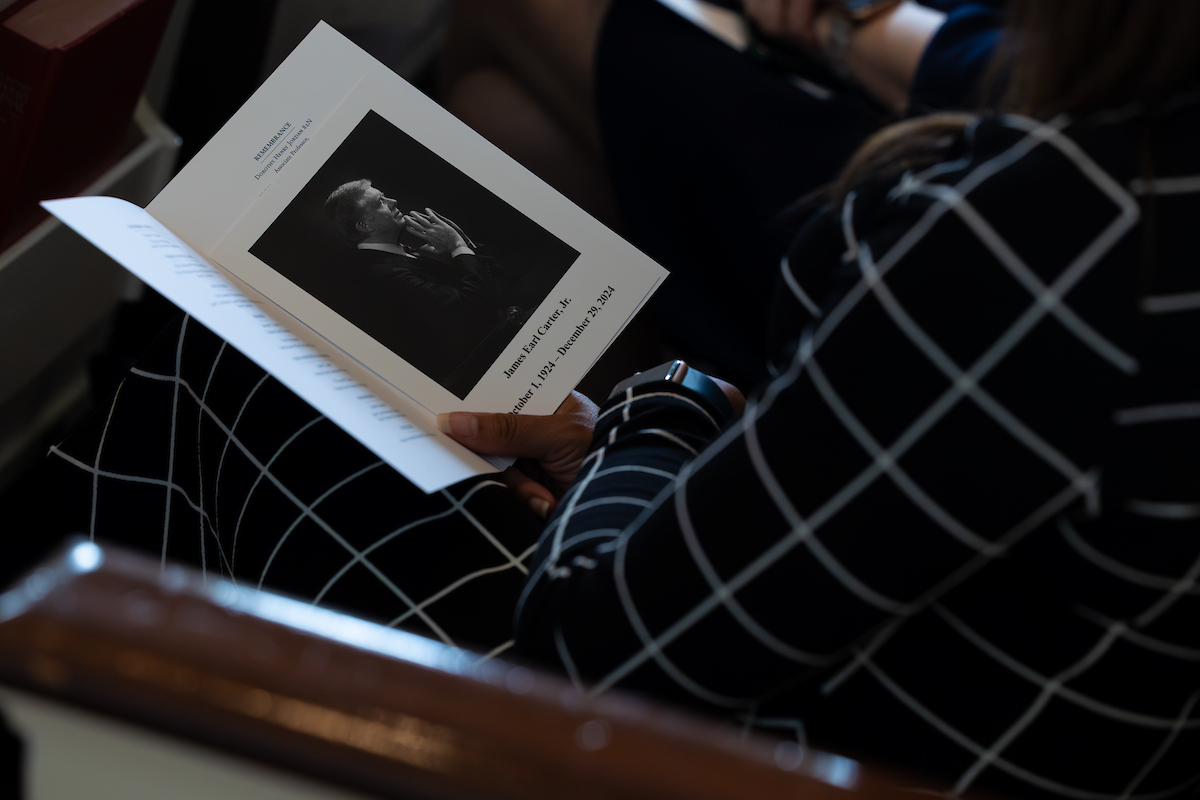

On Monday, Feb. 10, members of the Emory community gathered to remember Carter at Glenn Memorial United Methodist Church, joined by more than 700 online viewers. “Celebrating the Life of President Carter” featured a program of speakers, music and reflection honoring the legacy of the late U.S. president and Emory University Distinguished Professor following his passing on Dec. 29, 2024.

Emory President Gregory L. Fenves opened the event by reflecting on the longstanding partnership between Emory and Carter.

“The Emory community came to know Jimmy Carter one small, indelible interaction at a time,” Fenves said. “To the people of the United States, Jimmy Carter was an American president. To the citizens of the world, he was a humanitarian of grace and integrity. But at Emory, he was simply our president. We felt a sense of pride in his accomplishments. He embodied the ethos of Emory like no one in our history.”

Former Emory presidents James T. Laney, William M. Chace, James W. Wagner and Claire E. Sterk shared their memories of Carter in video reflections.

Unparalleled service and diplomacy

Generations of Emory students, faculty and staff interacted directly with Carter during his four decades as Emory University Distinguished Professor. He often visited classes, gave talks, met informally with faculty and fielded questions from first-year students at his annual Town Hall.

The Rev. Dr. Gregory McGonigle, dean of religious life and university chaplain, welcomed those in attendance, noting the university’s close relationship with the Carter family: It was in the same space, Glenn Memorial, he said, that the university hosted the national tribute service for Rosalynn Carter, who passed away Nov. 19, 2023.

“As we reflect on his remarkable journey,” said McGonigle, “and, in a special way, on his connections with Emory, may we find comfort in the example he set … that will continue to inspire us for generations to come. May this gathering be not only a memorial, but a celebration of a life very well lived, a life devoted to service that made a profound difference.”

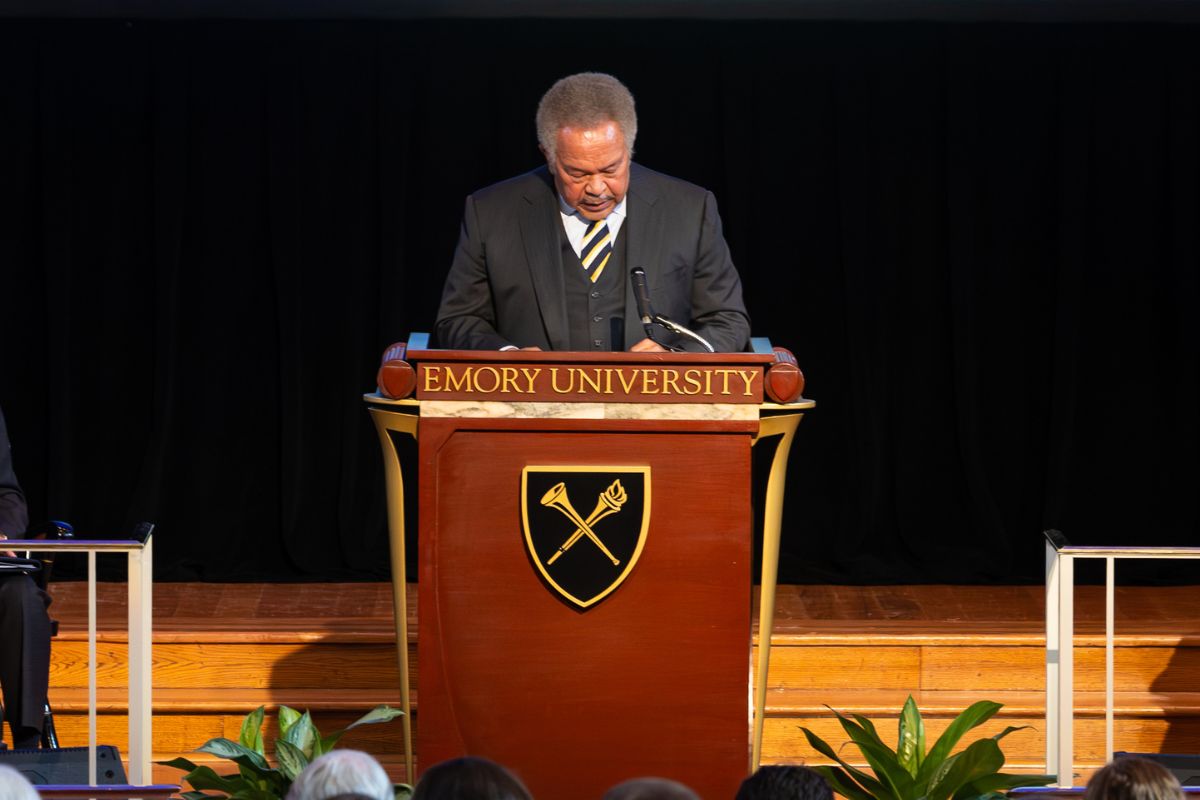

Carter’s many accolades include the 2002 Nobel Peace Prize, noted the Rev. Dr. Robert M. Franklin Jr., the James T. and Berta R. Laney Professor in Moral Leadership at Candler School of Theology. Carter was honored for his achievements in international conflict resolution, advancing democracy and promoting human rights as well as economic and social development.

Franklin called Carter a “rock-and-roll president who sought to orchestrate harmony among the many hues and spiritual paths of humanity.” Noting Carter's humble beginnings, Franklin said, “We offer thanks for this American classic, this farmer intellectual who cultivated bold visions for peace with the same hope and determination with which he cultivated the bountiful soil of Plains ... Jimmy Carter, we will cherish thy memory."

It was Carter’s diplomatic achievements — such as his brokering of the Camp David Peace Accords between Israel and Egypt in 1978 — that inspired Sharon Stroye to attend the campus service.

“I came out today because his life represents all of the work I do,” said Stroye, director of Emory’s Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion’s Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation Initiative. "You bring people from different backgrounds together for courageous conversations” that are often difficult, she said. “But once you’re able to do that, then that leads to transformation. And that’s what everything in his life was about: bringing people together to talk about solutions.”

Embodying the ethos of Emory

Paige Alexander, CEO of The Carter Center, remarked on the importance of the memories Carter left behind and how they provide a roadmap to a better future.

“We have these memories because he left us with a legacy to build, to make sure that we were not just trying to save the world, but we were doing something about it,” she said. “We’re able to do that in many ways because Emory is here helping us, whether it’s the research and development work we do or the students who are interns from Emory.”

The Carter Center, which has worked to resolve conflict, advance democracy and prevent disease around the world since its inception in 1982, got its start on the 10th floor of Emory’s Woodruff Library.

Through the years, generations of Emory students have served at The Carter Center as interns.

Emory students have also pursued careers at The Carter Center. Ariane S. Ngo Bea Hob, senior technical coordinator of the center’s Chad Guinea worm program, shared reflections over video. Hob holds a master’s degree in public health from Emory’s Rollins School of Public Health.

It was fitting, then, to hear from Emory’s Jimmy Carter Professor of History, Joseph Crespino about other ways Carter influenced Emory students. Crespino is also senior associate dean of faculty and divisional dean of humanities and social sciences.

In his remarks, he shared memories of working with the former president to develop a seminar that explored Carter’s life’s work. Students did research in the archives at the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and wrote papers on their findings. For the final class, Carter visited with the students — and he made sure to engage with them as sincerely as possible.

“It was amazing to see the seriousness with which he took the assignment, and the humility,” Crespino said. “President Carter was never pontificating. He was never just recycling old stories. He was always answering students’ questions as earnestly and fully as he could.”

“As a historian,” he added, “I believe that the values that I saw President Carter practice in an Emory classroom — values of humility, of optimism, of faith in the potential of his fellow human beings to act with reason and goodwill — are the same values for which Jimmy Carter will be remembered as a president and as a statesman.”

Caring as a ‘radical notion’

Dorothy Henry Jordan, associate professor in the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, recalled an instantaneous connection with Carter over their shared commitment to caring for people in need. That connection marked the start of a close relationship that spanned decades.

During her remarks, Jordan noted the nursing work of his mother Lillian Carter, the namesake of Emory’s Lillian Carter Center for Global Health and Social Responsibility.

“President Carter grew up in a time where caring for all people equally was something of a radical notion,” Jordan said. “But he worked to make his mother’s extraordinary compassion ordinary, to leave the world a healthier, kinder and more equal place than he found it.”

Jordan noted the profound impact of Carter’s loss. But she expressed a deep appreciation for the groundwork he laid throughout his life so that scores of people at The Carter Center, Emory and beyond could continue his legacy.

Memories of home: Emory, Plains and Habitat for Humanity

Carter’s close-knit relationship with Emory was an inspiring factor for several in attendance, including Janell Goodwin-Farley, senior events coordinator in Emory's Campus Life division, who has worked at the university for nearly four decades.

“I’ve been around President Carter my whole life,” she said, recalling the first time she met him as an 11-year-old during a visit to campus with her mother, who also worked at the university. “I grew up at Emory.”

Carter’s impact on her life, she said, extends far beyond an occasional warm greeting. She noted that her cousin lives in a Habitat for Humanity home — “an orange house, three bedrooms, screened-in porch with nice little yard” that was erected in the early 1990s.

The Carters led Habitat’s “Jimmy & Rosalynn Carter Work Project” for more than three decades.

“The service is very personal to me, because he contributed to my family,” Goodwin-Farley added. “To see [my cousin] raise her kids in that home — and now her grandchildren — and to see the impact it’s had on her family, it means a lot to me. And that’s one of the main reasons I’m here.”

In the 1980s, Carter began teaching Sunday school classes twice a month at Maranatha Baptist Church in his hometown of Plains, Georgia — a practice he would continue through 2019. The classes drew people from all over the world, including strangers, humanitarian partners and close friends.

Don Saliers, William R. Cannon Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Theology and Worship, was among the many to make the pilgrimage to Plains. Over his 50-plus years at Emory, he developed a friendship with the former president.

“He taught Sunday school like he was teaching to ordinary folks, but the world was there,” Saliers said, adding that after the class, Carter took the group for ice cream and, of course, peanuts. “Quite apart from the presidency, he was, as they say, a mensch. He was a man. He was a soul. And the two of them together — he and Rosalynn — it was a duet we won’t see again.” The event closed with all in attendance rising to sing the hymn “Let There Be Peace on Earth” accompanied by Saliers on organ.

Terry Ward graduated with a master’s degree from Candler in the 1980s and interned at The Carter Center in its early years. He remembers a one-on-one meeting with Carter where the two discussed the center’s then-burgeoning human rights initiatives. He was struck by “the laser beam of focus [Carter] brought to life in an unprepossessing way.”

Ward now lives in Massachusetts and flew to Atlanta the morning of the campus service.

“When he died, I knew there would be stuff in Washington,” he said. “And I watched it, and it was all good. But I said, ‘If there’s something at Emory, I’m going to go to that.’”

A sense of humor and a tireless spirit

From professional endeavors like leading health programs at The Carter Center and very nearly eradicating illnesses like Guinea-worm disease, to avocations like furniture-making and writing books, Carter was a true polymath.

That’s rare, indicated famed epidemiologist William Foege during his remarks. Foege served as The Carter Center’s first executive director and fellow for health policy and was appointed by Carter to be the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) director in 1977. Today, he is Presidential Distinguished Professor Emeritus of International Health at Emory.

“After his third book had been published,” Foege recalled, “I said to him, ‘You might set a record for number of books published by a president!’”

Carter’s quick response took Foege by surprise: “‘What’s the record?’”

Carter, possessed of both a keen sense of humor and competitive spirit, did set that record, going on to publish more than 30 books.

Foege closed his remarks with a story about visiting Plains for a Carter Center meeting on global health. When he arrived, he noticed that Carter had a small cut on his lip. He later learned that the president had received that cut when he ducked to avoid hitting a branch while mowing the church lawn, hitting his lip on the riding mower’s steering wheel.

“Think of that,” he told the hushed crowd. “The president mowing the lawn at the church with no publicity. But then, I find that Mrs. Carter, at the same time, is in the church, cleaning the bathrooms … These people walked amongst us.”

That sense of humility and devotion to service was foremost in Andrew Sherrill’s mind while attending the service for the man he called “my favorite president.”

Yes, Carter was rightfully lauded with international honors, commanding respect around the world. But it’s the quiet choices he made every day that made him truly great, Sherrill said.

“It’s living his values, right?” said Sherrill, assistant professor in Emory School of Medicine’s Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. “We can live life devoted to making ourselves feel good, or we can experience a lot of discomfort — and he did that. I think that takes a lot of courage.”

The Voices of Inner Strength Gospel Choir sang “Your Love Divine” led by Maury Allums, director of music in the Office of Religious and Spiritual Life. Allums also performed gathering and postlude music on piano.

In his closing remarks, Rabbi Jordan Braunig, Emory Jewish chaplain, asked the audience to reflect on Carter's enduring legacy: “What does it mean for a memory to be a blessing? Perhaps it means that even beyond a person’s life, they have the opportunity to inspire and to guide us.”