The 2024 Muscogee Teach-In recently brought together students, faculty and staff from across Emory with members of the Muscogee Nation to learn about the tribe’s history and culture.

The annual teach-in, now in its third year, began as a collaborative program with the Muscogee Nation. It was born from conversations held by the Indigenous Language Path Working Group starting in late 2021 on how to address the displacement of Indigenous tribes from the Southeast.

Emory’s Oxford and Atlanta campuses sit on land originally occupied by the Muscogee people. In 1821, 15 years before the founding of the university, the Muscogee were displaced.

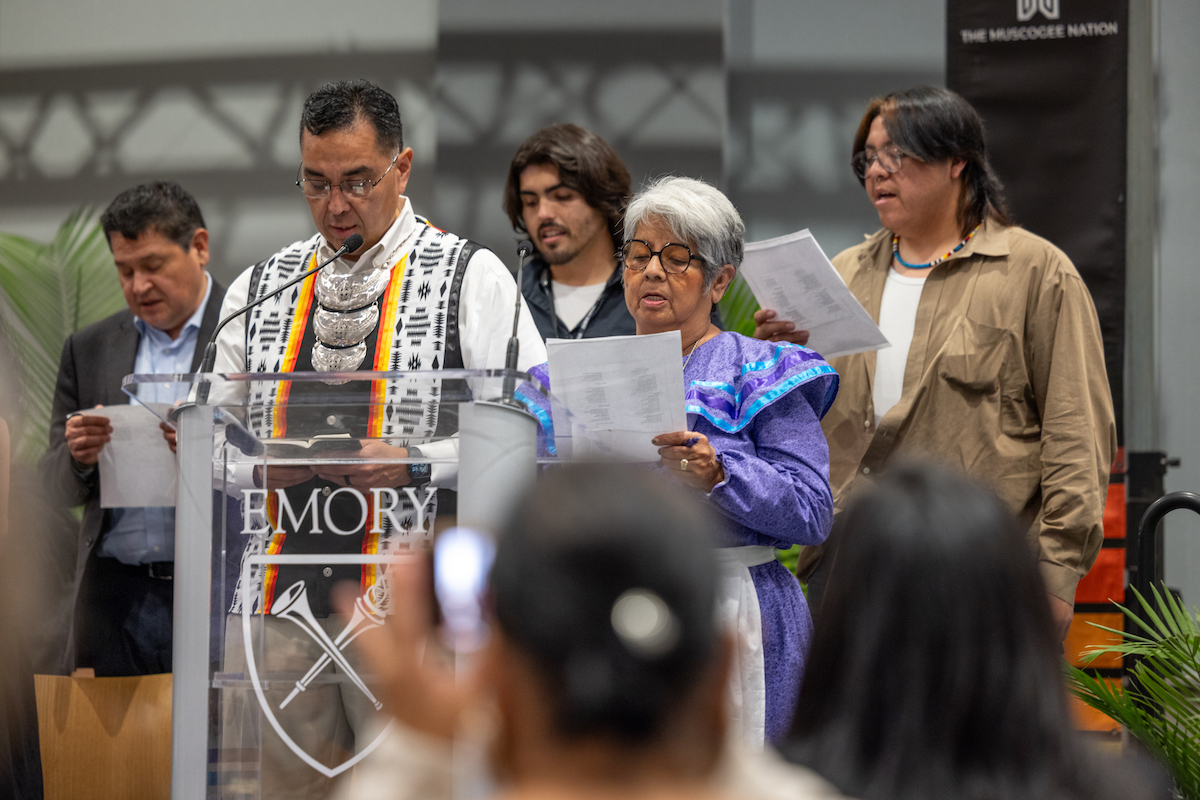

Now, the Muscogee Nation and the College of Muscogee Nation (CMN) work with Emory College of Arts and Sciences each year to develop a program that highlights different aspects of the tribe’s culture and helps to preserve its linguistic practice. Citizens of the Muscogee Nation then lead the event.

This year’s program included Muscogee hymn-singing, a community stomp dance and other demonstrations of arts and culture. Thirteen students from CMN’s Mvskoke Field Lab course were in attendance and, before the event, spent time in the Rose Library and Lullwater Park as part of their immersive learning.

Beth Michel, senior associate director at Emory’s Center of Native and Indigenous Studies in Emory College of Arts and Sciences and one of the organizers of the event, says the teach-in offered a momentary reframing of how Emory often views itself.

“Emory is usually a leading institution [known for its experts and expertise],” Michel says. “But for that time, we’re actually learning; we’re the students. The Muscogee Teach-In is led by the nation’s members, and it’s an opportunity for their community to educate us. The Nation is raising awareness that Muscogee people are still thriving in 2024.”

Tre’ Harp III, a senior studying human health and president of the Emory Native American Student Association, delivered the event’s opening address. The teach-in also featured remarks from Muscogee leaders and Heidi Senungetuk, Emory assistant teaching professor of music.

Harp has attended each of the three teach-ins and has seen the event — and the relationship between the Emory and Muscogee communities — develop over the years.

“I’ve grown with this movement to build community with the Muscogee Nation,” says Harp, who is Muscogee and Choctaw himself.

“Seeing how much work has gone into the teach-in and the amount of people who attend the event who are genuinely here to connect with Native American and Indigenous perspectives, it makes me feel whole,” he adds.

Michel says hearing the Muscogee hymn in its original language was “a powerful moment.”

The mvhayv — Muscogee for teacher — had planned to lead the group in song by herself, but once on stage, she asked the CMN students who were familiar with the words to join her.

“That was inspiring to me — how awesome it was to see the students speak their first language and quickly support their Elder with the hymn songs,” Michel says.

Harp looks forward every year “to the feeling of community when everyone is stomp dancing together. It’s a thing we can share, bringing together both communities in a special way. It’s very sacred, but it’s also very community minded.”

The stomp dance is an intimate tradition, and its inclusion in the teach-in provides a unique opportunity for the Emory community, Michel says.

This year the dance took place on McDonough Plaza. It had been raining the day before, so the ground was wet. Ryan Hill, from shanûnû ceremonial ground, led the dancers and started off by the fire pit, where much of the grass had already dried. But as they continued, he took them across the damp soil.

Michel noticed that nobody seemed to mind; everyone was in the moment.

“I was worried someone would step out of the dance because we were in the mud,” she says. “But to see all of the attendees accept that we were in this grassy and muddy area and value the lead singer’s decision to take us beyond the pit, that signaled to me that people understood what we were doing. When our ceremonial leader says the dance is over, then we can respectfully disperse. And that’s what happened.”

Photos by Avery Spalding, Emory Photo/Video.