If junior Alisha Morejon was told when she became a student fellow for Emory’s Center for AI Learning that in less than a year, she would be co-authoring a research paper and traveling to Canada to present her work at an international conference, she never would have believed it.

“I’m still surprised at all the new experiences I’ve been exposed to as a student fellow. It really has taken me to places I never imagined and taught me so much about myself in the process,” says Morejon, who is a joint computer science and mathematics major.

To cap off her first year working at the Center for AI Learning, Morejon plans to travel to Ottawa this summer for the Annual International Meeting for the Society for Psychotherapy Research. There she will help present the paper “Using Machine Learning to Explore Ugandan Children's School Readiness”—a rare opportunity for an undergraduate student.

The Center for AI Learning, which opened its doors in fall 2023, is a key component of Emory’s AI.Humanity initiative — an enterprise-wide commitment to shaping the future of ethical AI to serve humanity. As part of its programming to build AI literacy and community at Emory, the center offers experiential learning opportunities to Emory students, providing them with practical experience applying AI concepts to real-world projects.

When hired, student fellows sign up for a paid position of 10-15 hours per week. A certain number of hours are spent in the center’s physical location in Woodruff Library where they greet visitors and answer questions about the center and its offerings. Each student is assigned to experiential learning projects in which they work directly with sponsors to solve a problem using AI. They are also required to teach an in-person workshop on a chosen subject each semester.

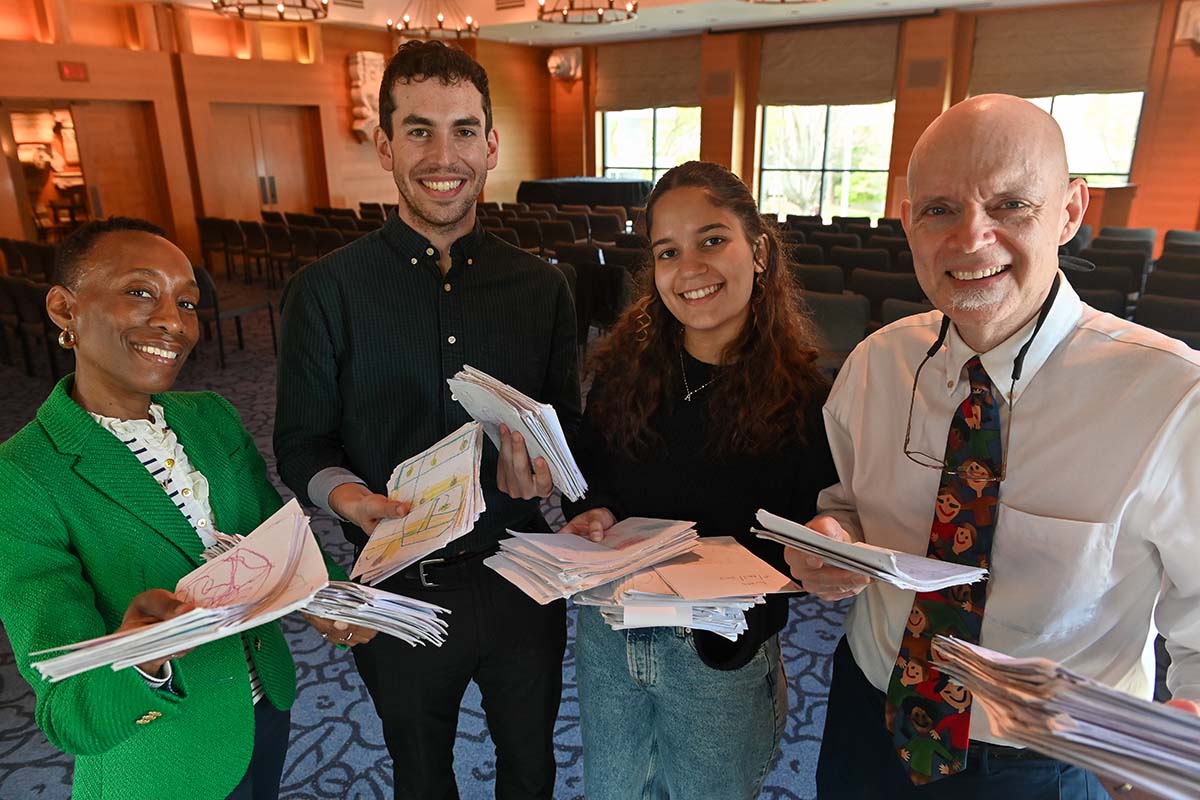

The center’s senior program coordinator, Tommy Ottolin, matched Morejon with project sponsors Valeda F. Dent, vice provost of libraries and museum, and Geoff Goodman, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences in Emory University School of Medicine and associate professor of psychology and spiritual care in Candler School of Theology.

Dent and Goodman approached the center to help with a project that grew out of their long-term research collaboration in early literacy intervention. Their project, “A Story Grows in Uganda,” has generated over 40,000 drawings from children in rural Uganda aged three to five. They wanted to use AI to help them categorize the vast trove of artwork and come up with patterns that could give them insight into the children’s development and readiness for school.

“I think Tommy chose to have me work on this project specifically because of my interest in the humanities,” says Morejon, who is a religion minor. “I tend to look at the big picture and strategy over the super technical aspects. I’m the one who analyzed all the existing research, looked at different angles and said, ‘Hey, did we think about this?’”

Each drawing requires feature-based coding, an extremely time-consuming prospect. The objective was to automate the process of coding these pictures using deep learning models.

Morejon and her partner, another student fellow who had more programming experience, did encounter several roadblocks along the way.

Around 200 drawings came to them already analyzed and coded by researchers on Dent and Goodman’s team — a relatively small sample of training data. The process they designed involves using supervised learning in which the model is fed 70% of the training data with labels and then given 30% of uncoded drawings to test for accuracy. The results so far have been less than perfect.

“We are still in the trial-and-error phase,” says Morejon.

But the potential short- and long-term impacts are worth their persistence. Once realized, this project will make the herculean task of coding thousands of drawings achievable. In addition, storing the data of each drawing digitally will be a great resource as the team continues tweaking the model to detect novel patterns. If meaningful patterns are extracted, an intervention could be designed to increase literacy outcomes and school readiness in the developing world — and that’s the kind of real-world challenge that AI.Humanity was designed to address.

Morejon learned not only about machine learning methodology but also about herself. “I was having a lot of fun. Finding the intersectionality in this project has been really interesting,” she says.

A multitude of benefits

The beauty of the center’s student fellows program is that the learning goes far beyond the projects themselves. Ottolin, who calls the projects “real-world adventures,” explains that built into each is the expectation that the students actively participate in brokering relationships, managing the evolution of the project, communicating with clients and troubleshooting. These non-technical skills are equally important in preparing students to flourish in a rapidly changing world — a key tenet of the Student Flourishing initiative.

Project requests are fielded in many ways: emails, calls, walk-ins. Once a project has been evaluated by the center staff for feasibility as a student-led project, a project proposal document is completed. The document includes details on the project sponsor, which student fellows will be assigned to the project and what their roles will be, project objectives and measures of success.

Given that the center and its student fellows program are relatively new, there are constant adjustments being made to how projects are set up and carried out.

“I tell every student we interview that we are learning as we go. This is a really cool place to work. If you can be nimble and transparent and be ready to incite change, then this would be a good fit for you,” says Ottolin.

Ottolin adds that project sponsors understand that this is a learning opportunity for students — and that sometimes includes setbacks and failures.

“We’re working with new technologies and answering new questions. Sometimes things aren’t as straightforward as we originally thought,” says Ottolin. “I have to hand it to our sponsors. They’ve been great partners and have been very cognizant of the environment we want to build for these students. Lessons learned can be lessons about what not to do, too.”

At the center, I wanted to apply my skills but I also wanted to immerse myself in the world of AI. With the prevalence of technologies that are part of our everyday life, it’s important to stay ahead of the times. I appreciate Emory’s initiative to push forward AI education.

Making the theoretical tangible

Another undeniable benefit of the center’s experiential learning projects is the prospect of turning the theoretical into something tangible.

Student fellows Dylan Parker and Raphael Palacio, both computer science majors, are working on a chatbot project for the Emory Ombuds Office. Palacio has also taken CS 329: Computational Linguistics, and Parker is taking it now; while one of the major projects in that course involves designing and building a chatbot, Parker says he appreciates the opportunity to apply his technical skills outside of the classroom.

“The Ombuds chatbot project is a good complement to what I’m learning in class. This semester I’m taking Intro to AI, so I get to learn the theoretical side of AI and then get to apply that knowledge,” says Palacio.

Solving problems, saving resources

Beyond applying learned skills, students also have the chance to make a lasting impact by solving an authentic problem.

That is just what student fellow Iris Zheng did in her work for Emory’s Morran Lab and its Population Biology, Ecology and Evolution Program. Researchers in the Morran Lab use c. elegans worms for coevolution and mating systems research. Researchers must manually count and classify thousands of worms under a microscope each week. This tedious process can take hours or even days and has a highly variable rate of error.

Zheng, a double major in biology and computer science, was given the task of creating a deep learning model that automates the process of counting and classifying the worms while minimizing errors.

Zheng says she faced two big hurdles during the project. The first was lack of adequate training data, a common theme in AI model building. In this instance, existing data would train the model to analyze patterns, features and thresholds. Zheng and her partner, another AI student fellow, had to mitigate the data shortfall by finding accessible datasets from other sources.

Another challenge was the self-guided learning process in object detection and convolutional neural networks (CNNs). Zheng had little experience in these areas, so she and her partner had to learn about the underlying logic, math and implementation from the ground up.

“The self-education process was arduous and at times, frustrating. It required a great deal of patience and persistence, as we had to digest complex concepts and apply them to our work,” says Zheng. “There wasn’t an easy solution to this problem, but I did learn through grinding and now I have a totally new skill set that will serve me in the future.”

The result is a tool that saves the research team four hours of counting each week, freeing them up to spend time on other aspects of their research. Since c. elegans are one of the most common organisms used in lab science, the new tool could potentially be used by other researchers to save time, eyesight and eliminate human error.

The project was an intensive learning experience in artificial intelligence, coding, professional communication and teamwork. It expanded my understanding of machine learning's limitations, practical applications and impact. I enjoyed building a solution from scratch, and blending theory with practice was valuable and gratifying.

The future of experiential learning at the center

As summer approaches, the center’s experiential learning opportunities are expanding. The center has partnered with academic units like the Department of Quantitative Theory and Methods and courses like CS 370: Computer Science Practicum Course – LLM, Data Analytics and Visualization to offer co-curricular and classroom experiential learning. There are also external opportunities through the City of Atlanta’s Office of Technology and Innovation and more partnerships on the way.

“When we think about the AI.Humanity initiative, we are trying to shape our students into the most well-rounded AI professionals. So that’s not just writing code in a room by yourself — we want to expose them to the full gambit of working on a team, nurturing a client relationship, managing a project, solving problems,” says Ottolin. “And while solving these problems, they are looking at the process through a lens of ethics and fairness. That’s what Emory and the center’s experiential learning projects bring to the table — a chance to learn, grow and make a difference to humanity.”

Interested in exploring experiential learning or have an idea for a project? Reach out to the Center for AI Learning team.