The Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library at Emory University is home to collections of archives and papers created by some of the most studied authors and poets of the past century, including many of Ireland’s most inspiring writers. This globally significant collection — with papers from Seamus Heaney, W. B. Yeats, Michael Longley, Derek Mahon, Paul Muldoon, Ciaran Carson, Rita Ann Higgins, Edna O’Brien, Thomas Kinsella and Medbh McGuckian — is one of the Rose Library’s best-known collections.

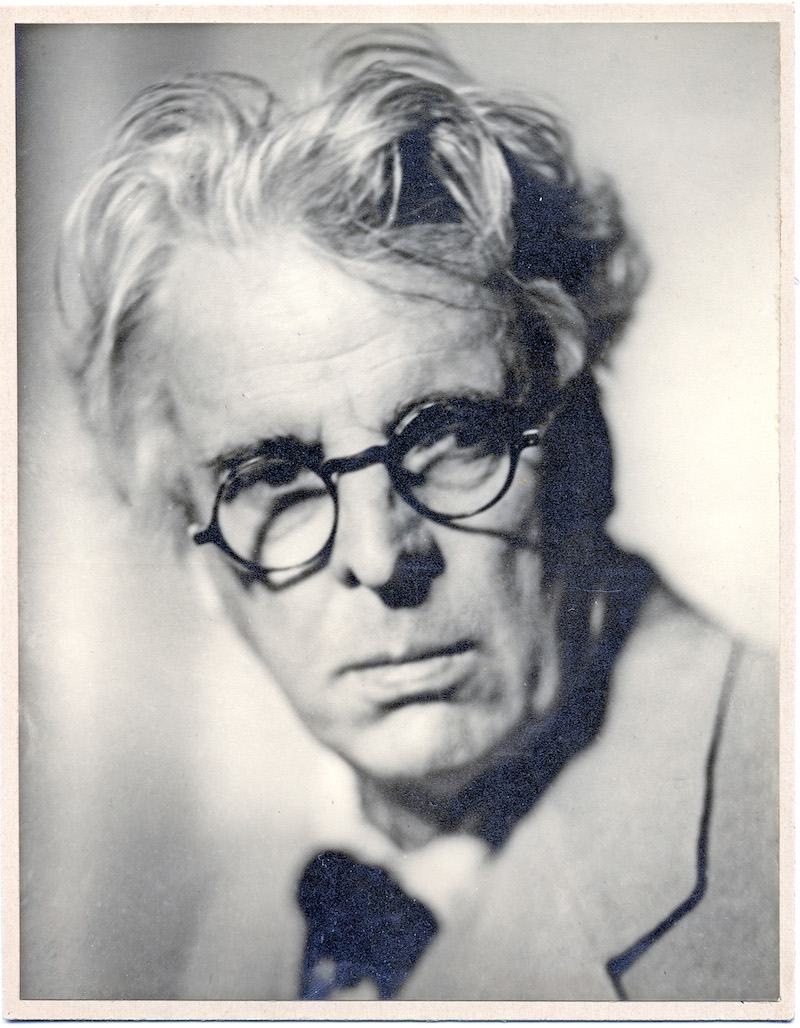

Portrait of Irish poet and playwright W. B. Yeats. From the W. B. Yeats collection, Rose Library at Emory University.

Currently, researchers and students must visit the Rose Library in person to use many of the collections, as with most literary archives. In-person use is a challenge for researchers who are not on campus — and especially for the hundreds who travel across the U.S. and the world to use the materials.

A virtual reading room would help make it possible for researchers to access collections without requiring travel.

“In this digital age, libraries must find opportunities to establish new ways to share resources,” says Jennifer King, director of the Rose Library and principal investigator for the grant application. “The Rose Library is excited to advance a more inclusive model for access and engagement with cultural heritage collections. We see this planning grant as a first and critical step toward a future where even rights-restricted writers’ papers will join our growing digital library and be available to users worldwide, without requiring the resources necessary to travel to Atlanta.”

While the focus of this grant is Irish literature and poetry, the outcome will contribute to improved online access to all copyright-restricted works from across collections that include African American history and culture, as well as political, social and cultural movements.

The two-year planning phase and trial period will include hiring a project manager. Rose Library will partner with the National Library of Ireland and the Seamus Heaney Centre at Queen’s University Belfast on the planning and pilot project.

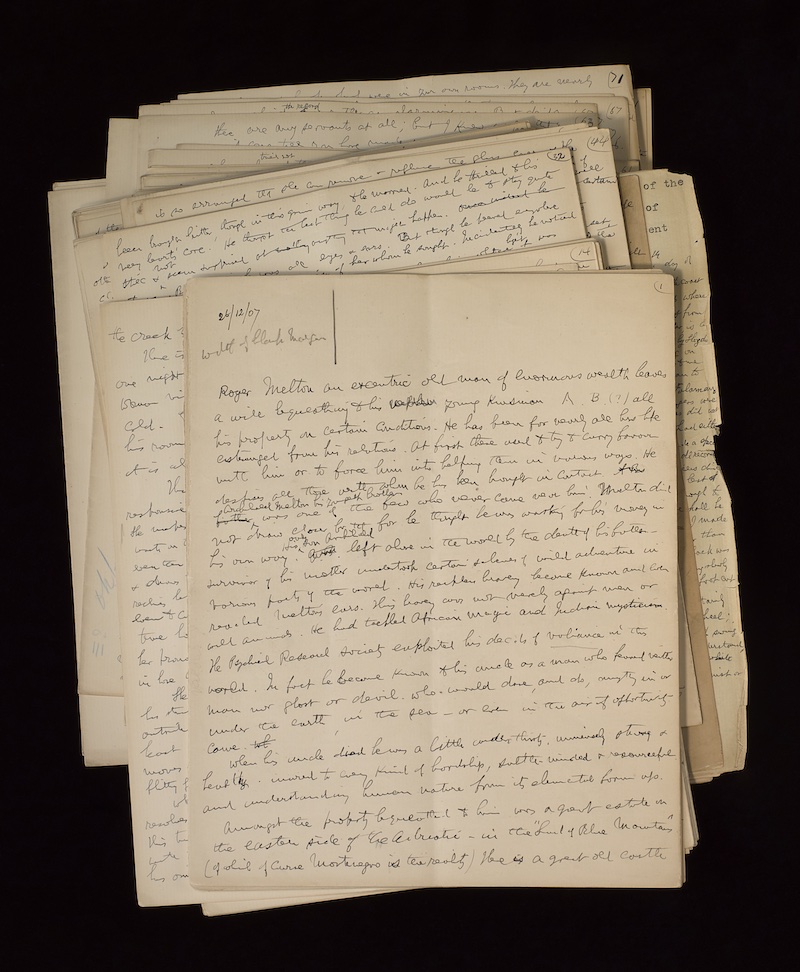

Manuscript, “Lady of the Shroud” by Irish writer Bram Stoker, author of “Dracula.” From the John Moore Bram Stoker Collection, Rose Library at Emory University.

Project partners in Ireland agree. “The virtual reading room will provide audiences in Ireland, as well as all those interested in Irish literary culture throughout the world, access to the Rose Library archives of Irish authors and poets,” says Audrey Whitty, director of the National Library of Ireland. “This initiative will place the needs and interests of communities and scholars outside of Emory at its heart, by addressing barriers to engagement more broadly and establishing access to this highly significant cultural collection.”

Glenn Patterson, director of the Seamus Heaney Centre at Queen’s University, adds how “pleased we are to be one of your partners on the planning phase and trial period.”

Protecting copyrighted materials

The National Library of Ireland is a partner in the virtual reading room pilot project, led by Emory’s Rose Library and funded by a Mellon grant. Credit: Marc O’Sullivan, courtesy National Library of Ireland.

One of the biggest issues facing the team is how to protect the copyrighted materials once they are digitized and available online. In physical reading rooms such as those operated by Rose Library and other archival institutions, policies and procedures are in place to prevent theft and communicate copyright requirements, and a staff member supervises patrons using the materials. Emory’s Scholarly Communications Office is a significant partner in this work, helping the team address copyright considerations.

“A key question for the pilot will be how to implement a virtual access model that safeguards the rights of authors,” says John Morgenstern, copyright and scholarly communications librarian. “The virtual reading room’s international dimension will require an analysis of legal frameworks in both the U.S. and Ireland as well as invaluable consultation with rightsholders.”

Another benefit of the pilot program? The team will be able to discern how many people have been waiting for this kind of digital access because they have been unable to visit Rose Library in person.

“The difficulty in getting direct knowledge of people who aren't able to come and see the collections they need to use is one of the reasons we’re undertaking this project,” says Katherine Fisher, head of Rose’s digital archives and the grant’s co-principal investigator. “We think there is an additional user community we're not reaching, and this is a way for us to gauge how much interest is out there.”

“If we can meet potential users where they are and put things in front of them,” Fisher adds, “that gives us a chance to start a conversation about what they want and what they can do with the collections — and how we can better serve a wider audience.”

Meeting the demand for digitization

Rose Library already offers some significant digitized collections. The Emory Digital Collections platform allows users to browse images and documents from approved collections (only copyright-cleared materials can be downloaded and used with proper citation).

Some of the Rose materials in this digital collection include highlights from the Emory University Archives, such as the Robert Langmuir African American Photograph Collection and the yellowbacks collection, with scans of 135 Victorian-era novels from the late 1800s and early 1900s that helped increase literacy beyond the upper class. Poetry materials in the digital library include the exceedingly rare handwritten copybook from Phillis Wheatley, the first African American author of a published book of poetry, and items from the Gregory family papers. These poetry materials are available because they are in the public domain, a status not achieved until 70 years after an author’s death.

“In a regular year, we host about 1,000 researchers in the reading room that include scholars, students, artists, authors, filmmakers, curators and others,” King says. “But our online collections have exponentially more exposure — registering 460,000 uses last year. The level of use is significant.”

“The goal of putting the collections online is not just to digitize everything,” King adds. “We want to learn more about how people use collections online and make sure that there aren’t financial and other barriers to engaging with archives. We want to build library services that promote engagement in partnership with the communities that we document.”