When Michael Roberts felt under the weather last fall, he didn’t think anything of it at first. A healthy, physically active young man, he figured he would bounce back within a few days.

The next night, he started coughing up blood. Although he felt so weak he could hardly get into his truck, he drove himself to the emergency room at Grady Hospital, where he was initially diagnosed with a bad case of the flu.

“I made it to Grady and told them I didn’t know the protocol, but that I couldn’t breathe,” Roberts remembers. “They took my information and vitals and then took me to the back. I remember having a phone call with my mom, but right after that, the lights went out.”

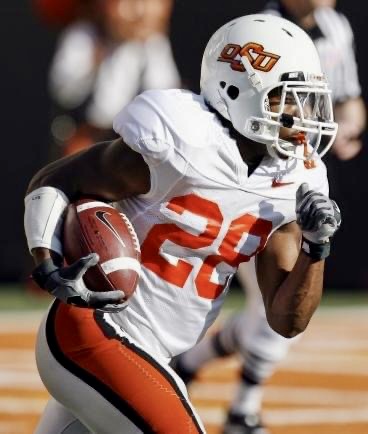

Roberts runs the ball for Oklahoma State University in 2008, during a game against Missouri State University.

In the ER, Roberts was placed on a ventilator along with three types of medication to keep his blood pressure and heart rate up. The next day, Nov. 1, he was taken from the emergency department to the intensive care unit (ICU) and continuously required more support from the ventilator.

At the same time, Sagar Dave, DO, was working in Emory University Hospital’s (EUH) cardiovascular ICU, where he serves as associate medical director. Dave got a call from a colleague at the medical ICU at Grady, asking if Roberts would be a candidate for the Emory ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) Center, which Dave also co-leads.

Dave and his team looked at Roberts’ case and identified that he might be going into complete respiratory failure driven by the flu or viral pneumonia. While most patients will recover relatively quickly from a bout of flu or pneumonia, both can cause additional problems such as organ inflammation, sepsis, or multiple organ failure, among other issues.

Due to the amount of medication Roberts was on at Grady, Dave requested that the team perform a cardiac ultrasound to get a clearer picture of what was happening. His instinct was correct — the ultrasound showed that Roberts’ heart was weak.

A few hours later, his lungs seemed to be improving and he was stable enough to be transferred to EUH. But by the time Roberts arrived, his lungs were no longer the primary problem — his heart was. Within the first 24 hours, the team at EUH placed Roberts on a temporary left ventricular assist device (Impella), which is inserted through the axillary artery (which runs from the clavicle to the heart) by the shoulder and placed in the left chamber of the heart to improve blood flow and stabilize blood pressure.

After the impella was placed, they moved Roberts to the cardiovascular ICU, where his lungs intermittently declined and caused the right side of his heart to struggle to pump enough blood to the left side.

Sagar Dave, DO, associate medical director for both Emory ECMO Center and EUH CVICU, visits with Roberts in his hospital room. Dave offered not only medical care but consistent moral support throughout the recovery process.

Christina Creel-Bulos, MD, medical director of the Emory Healthcare ECMO program, was the receiving physician and attended to Roberts as soon as he arrived. Within 24 hours, the ECMO team had consulted over what to do, and Creel-Bulos had briefed Emory’s heart failure team, anticipating that some level of support would be needed from them as well.

All these experts were close to Roberts during his stay — while the heart failure team is in the three-floor cardiac ICU, they often consult in the Cardiovascular ICU, one floor above. Communication between the teams is open, too, and other experts at Emory are a mere phone call or text away.

Creel-Bulos also initiated conversations with Roberts’ family, explaining the different medical teams they might meet depending on how he responded to treatment. “Being early and assertive about involving multiple teams is key to making sure that our patients don’t have those long-term stays and complications,” she explains.

While Roberts’ family was thankful for the open communication, his critical illness came as a surprise. When Roberts was at Grady that very first day, his brother Tyrone visited, and was focused on getting the immediate issues taken care of (like moving Roberts’ truck) while anticipating that Roberts would be released within 24 hours.

“It was surprising because this was a young guy, a former college football player, who goes to the gym once or twice a day and he was fighting for his life with no clear reason why,” Tyrone says. “It was shocking that it turned so fast and that his heart was giving out on him for no real reason.”

Reflecting on how he was training before falling ill, Roberts explains that he feels like he was preparing for the fight of his life without even realizing it. But he’s no stranger to high-adrenaline situations. An all-around athlete and former running back for Oklahoma State University, Roberts also served as a military medic.

Roberts in his Army uniform in 2018, holding daughter Mylan, then just 6 months old and now five years old.

“Some of the emergency care training and the adrenaline rushes that I’ve had in my life, like playing in front of thousands of people in college, helped me work through the tough time I had here,” Roberts says.

ECMO, first invented in the late 1960s by Robert H. Bartlett, MD, and first successfully used in 1971, serves as a long-term “bypass machine.” ECMO supports the heart and/or lungs by taking blood out of the body, oxygenating it via an artificial lung, and pumping it back in.

While ECMO doesn’t treat or cure a disease, it offers time to heal and time for other interventions to work. Although there’s been an increase in treatment use since 2001, its usage radically jumped up during the COVID-19 pandemic, out of necessity for critically ill patients.

There are two types of ECMO: VA-ECMO, or veno-arterial ECMO, is used to support both the lungs and the heart. VV-ECMO, or veno-venous ECMO, is used to support only the lungs.

On Nov. 3, 2022, one day after the impella was placed, Roberts was transferred to the cardiovascular surgery ICU and placed emergently on VV-ECMO by Dave and his team for additional pulmonary support.

Roberts with his brother Tyrone in Athens, GA, during the University of Georgia vs Auburn game in November, 2018.

According to a 2021 study from Cambridge University Press, there are approximately 286 ECMO centers in the U.S., many of which are concentrated in metropolitan areas. While it is the most extreme form of life support, ECMO also better preserves quality of life and function. Emory is equipped to offer more atypical and advanced forms of support, which require not only the technology but also large, highly trained care teams.

For Roberts, the impella was removed a week later, but he remained on ECMO for more than two weeks. During most of that time, he was intubated, sedated and placed on a ventilator, and on Nov. 15, he underwent a tracheostomy, which surgically creates a hole in the windpipe to provide an alternative air passage.

That whole time, the cause of his original infection was never definitively identified. The team suspects Roberts may have had viral myocarditis secondary to viral pneumonia. On top of that, he developed a superimposed bacterial infection. Developing a viral pneumonia followed by a bacterial pneumonia is also seen with flu and other viral diseases, with incidence ranging from 26-43%. Viral myocarditis due to a viral infection, however, has an incidence of less than 1%, so the confluence of all three issues is relatively rare, according to Sagar Dave.

Austin DeBeaux, MD, served as the intensivist during two weeks of Roberts’ stay in the ICU and was responsible for day-to-day intensive care management, managing the ECMO circuit and coordinating with other consultants on this case.

“To not be able to have sure answers or know why this young man who was in great health was taken down by something he should’ve easily recovered from, it’s hard to not have those answers,” he says. When talking to a patient’s family in those situations, DeBeaux explains that he breaks things down into “what we know, what we hope for and what we’re doing today.”

Christina Creel-Bulos (left), MD, medical director of the Emory Healthcare ECMO program, and Austin DeBeaux, MD, CCM Fellowship Associate Program Director, were both part of Roberts' dedicated care team.

Roberts’ brother Tyrone remembers that tense and uncertain time vividly. But even as they searched for answers, what stood out to Tyrone was how caring and diligent the medical team at Emory was in keeping them apprised of Michael’s condition.

“The team was willing to break it down and go into great detail,” he says. “That made a lot of things easier because they were always available to answer any questions we had.”

Roberts’ family — especially his mom and brother, both of whom live in the Atlanta area — were nearly always around. Solid social support not only helps with a patient’s recovery but also helps each individual family member, too, DeBeaux explains.

The team closely monitored how Roberts responded to treatment and deployed best practices to give his body the time and support it needed to recover.

Helen Zackery, Roberts’ mom, was also impressed by how thorough and comprehensive her son’s care was. It was the first time she’d ever seen an ECMO machine at work. She remembers how carefully the doctors explained how this device would help save her son’s life.

They were right: VV-ECMO is a major reason why Roberts was able to walk out of the hospital after 36 days without long-term complications following his discharge from the hospital in early December 2022.

In fact, Roberts didn’t have to attend rehab of any type — including acute care rehab — something that Creel-Bulos explains is thanks to the large, multidisciplinary team at Emory, as well as how strong Roberts was before being admitted. During his stay, the nurses worked to keep Roberts off sedation whenever possible and he attended physical therapy even when on ECMO, something that Roberts remembers as very helpful toward his recovery.

“The doctors kept it real, they didn’t sugar coat anything, and we had a lot of bad days. But they still kept working, coming up with plans and telling me what they were going to try next,” Zackery recalls. “They never, I don’t care how bad things looked, they never gave up on Michael. They just kept working and working.”

Roberts with his mom, Helen Zackery, at his graduation from Oklahoma State in 2012.

Roberts’ personal background and competitive nature were strengths that his medical team made sure to leverage in his treatment plan.

Roberts was hospitalized in November — peak football season — and remembers his physician, Sagar Dave, stopping by his room during a particularly low period and asking if he wanted to watch TV. While they were rooting for their favorite teams, Dave started asking Roberts more questions about himself.

“He gave me motivation,” Roberts says. “As we watched football a little bit, he gave me little goals, like to try to do 8 hours off of the ventilator, then to stretch to 12 off of the air. So, in my head, I became competitive.”

Thanks to reaching for those goals, Roberts was able to move off of ECMO on Nov. 20. Eight days later, he showed enough improvement that he was moved out of the cardiac surgery ICU and into a general care room.

“I ran track and played football my whole life, so the way I’m wired is that if I’m here, I’m going to get through it,” Roberts says, explaining that bringing a competitive framework to his physical recovery at Emory made all the difference when the healing process felt like an all-out battle.

Dave said he was impressed by the positive attitude he witnessed in Roberts, who “always had a big smile and was interactive. It’s very hard to deal with critical illness, especially for a prolonged amount of time. Michael approached it as a challenge to conquer,” Dave says.

In fact, on Thanksgiving weekend, “the biggest issue he had was getting enough football games on the TV to watch,” Dave says.

Dave and Roberts share a warm smile during a recent check-in. Although the recovery process after falling critically ill last year has been painstaking, Roberts says, "I realized if I can go through the hardest, darkest part of my life, I can definitely get through anything."

Roberts’ mom, Helen Zackery, witnessed firsthand the trusting connection between doctor and patient, and how that bond helped her son on his journey back to his old self.

“Dr. Dave talked to Michael like he was family. Michael would just light up when he saw him,” she says. “The best doctors in the world worked with my son, and the best respiratory therapists in the world.”

For all of his progress, Roberts remembers some daunting nights when he couldn’t sleep, wondering if he’d ever make it out of the hospital. During those moments of doubt, he would think back to the encouragement he’d gotten from his care team – the doctors, nurses, respiratory therapists and speech-language pathologists who reminded him of how far he’d come.

“I was a shell of myself. I felt like my body had failed me and I couldn’t understand why. My recovery consisted of remembering who I was and that I went through a whole lot and my body fought and got me back to where I needed to be,” Roberts says. “The mindset that I have, being an athlete and a veteran, is that there are going to be a whole lot of things you don’t want to do. My role was to recover, and once I got in that mindset, the body really followed.”

Now, Roberts has reached his recovery goals and even started running again over the summer. Both Tyrone and Zackery are amazed at how far he’s come and say it’s great to see him back to being so physically active.

But it’s not just a physical recovery process. The healing happens mentally, too.

Roberts has been slowly but surely working through the trauma of what happened and relearning to trust his body. That process has been a bit slower, but Roberts added that the check-in texts he’s gotten from “Dr. Dave let me know I’m living, I’m alive, and it was well worth it to go through that.”

In fact, he says he wouldn’t change a thing about the past. “I realized if I can go through the hardest, darkest part of my life, I can definitely get through anything,” Roberts says. “Man, I was almost defeated. But I defeated it instead.”