Elberta Jenkins’ cardiologist delivered the news compassionately but directly. There was nothing else he could do for her. Jenkins had undergone a triple bypass in 2008 following a heart attack, but now, in 2020, two of the four main valves in her heart were failing. She needed another open-heart surgery, but she was no longer a candidate due to her age.

“I remember feeling hopeless,” says Jenkins, who is now 82. “But then my doctor said that even though he had run out of options for me, his former instructor and mentor, Dr. Greenbaum, was practicing in Atlanta, and he might be able to help me.”

That’s how Jenkins found her way from Orange Park, Florida, to the offices of Adam Greenbaum, MD, and Vasilis Babaliaros, MD, at the Structural Heart & Valve Center at Emory University Hospital Midtown. Greenbaum immediately recognized Jenkins as a good candidate for a noninvasive procedure Emory had helped pioneer, which he used to replace her aortic valve via a catheter. He hoped the new valve would give Jenkins the relief she needed.

It did not. She still suffered from the deterioration of another main valve in her heart, the mitral valve, which controls the blood flow from the lungs into the heart. She also had hypertrophic cardiomyopathy — a condition characterized by an overly large and stiff heart muscle. These conditions in combination greatly reduced the blood flow from Jenkins’ heart, and the enlarged muscle also blocked the space needed for a new mitral valve.

“She kept getting worse,” says Meri Pyle, Jenkins’ daughter who accompanied her mother on her doctors’ visits. “She got to the point where she could only walk a few steps before she’d have to sit down and rest. She started staying in bed, and she told me she just didn’t want to live like that.”

Adam Greenbaum and Vasilis Babaliaros review Elberta Jenkins' chart.

With open heart surgery off the table, Greenbaum tried the only other available method for shrinking the heart muscle to allow for the mitral valve replacement — killing off a section of the muscle by delivering alcohol via a catheter. However, he wasn’t able to complete the procedure due to the poor condition of Jenkins’ vessels. At this point, Greenbaum, too, was out of options for Jenkins — at least, tried and tested options.

“Dr. Greenbaum told us he wasn’t able to do that procedure, and that there were no others available, but he never told us he couldn’t help her,” says Pyle. “He just said, ‘Give us some time to think about it, and we’ll come up with a plan.’ He made us feel that there was a way forward, that he wasn’t going to give up.”

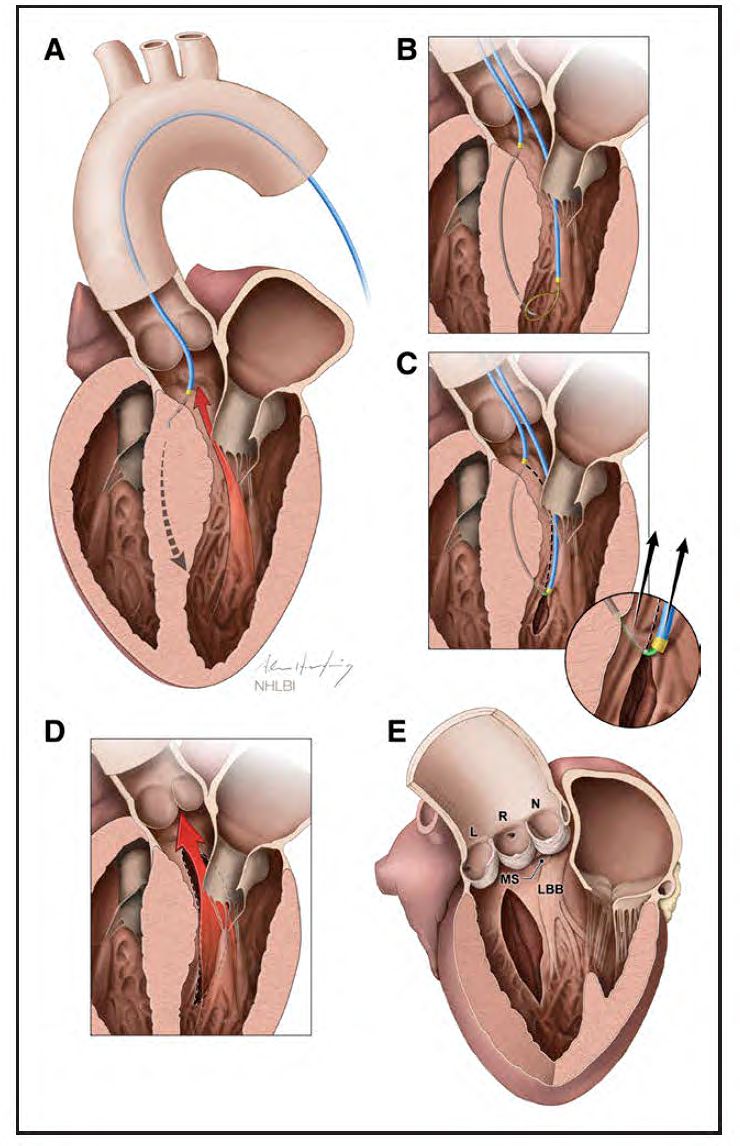

Greenbaum explained that he and Babaliaros had been playing around with a novel method of cutting the heart muscle with an electrified wire at the end of a catheter, which could create the space needed to put in a new mitral valve without having to open the chest. The procedure was still in the concept phase, being tested on pigs by a colleague, Robert Lederman, MD, and his team at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Greenbaum told Jenkins to give them five or six weeks to fast-track the testing and see how the pigs that underwent the procedure fared.

“When Elberta walked back in my office about a month later, her first words were, ‘How did the pigs do?’,” says Greenbaum. “I said they did just fine. And she said, ‘Then let’s go for it.’”

In January 2021, Greenbaum and Babaliaros performed the first ever procedure of Septal Scoring Along the Midline Endocardium (SESAME) on Jenkins. Several months later, he was able to replace her mitral valve.

“Once your older patients start getting orthopedic injuries because they’ve become so active, you know you’ve hit on something good.” - Vasilis Babaliaros

Today, Jenkins feels good. So good, in fact, that she resumed hiking until she had to take a short break when she twisted her ankle. “Once your older patients start getting orthopedic injuries because they’ve become so active, you know you’ve hit on something good,” says Babaliaros, founder and co-director of the Structural Heart & Valve Center.

The beginning of a beautiful friendship

Jenkins is but one of the latest in a long line of patients who have been referred to Emory when they have run out of options at other health centers. They come as a last resort to try novel options developed through a one-of-a-kind, decade-old collaboration between the Emory Structural Heart & Valve Center and the NIH.

Greenbaum was practicing at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit in 2013 when he was treating a heart patient who had exhausted all available treatments. He had recently read a paper about a new procedure being tested on animals at the NIH that he thought could help his patient. The lead author on the paper was Lederman, whom Greenbaum had met in the late 1990s when both men were working at Duke University.

Greenbaum contacted Lederman, who ended up going to Henry Ford to oversee the procedure being performed on a human for the first time. Greenbaum was able to use an electrified wire at the tip of a catheter to push the catheter through one blood vessel into another, a first in interventional cardiology.

The resulting successful transcaval aortic access procedure was the birth of catheter electrosurgery. It was also the birth of a strong and lasting collaboration between Greenbaum and Lederman, and later Babaliaros, who went to Henry Ford shortly after the success to learn the technique and bring it back to Emory. He recruited Greenbaum to join Emory in 2018.

Illustration of Septal Scoring Along the Midline Endocardium (SESAME) procedure, courtesy of Adam Greenbaum.

The three have been collaborating since to develop new catheter electrosurgery techniques, with the process following the same routine.

“We started getting referrals for patients who had fallen through the cracks, who didn’t have a solution that was either commercially available or in the mainstream research trials,” says Babaliaros. “We’d start thinking about what we might be able to do to help them, how we could modify our tool set to meet their need. We’d take the idea we came up with to the NIH to further develop it and test it on animals, and then we’d offer it on a compassionate care basis to these patients who had no other options.”

The entire process, from concept to implementation, could be as fast as several weeks, as was the case with Jenkins. “Traditionally, someone might come up with a new idea and take it to industry,” says Greenbaum. “They’d have to develop and test prototypes going through the Food and Drug Administration, and it could take 10 to 15 years before that device or technique is available. But some people don’t have that time. That fact that we can, through our unique relationship with the NIH, offer patients novel solutions sometimes within a month or two can save lives.”

A field ‘ripe for innovation’

It's not the first time Babaliaros and Greenbaum have been pioneers in the field.

Starting in 2007, Babaliaros was a primary participant in a trial of transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), a procedure that allows a new aortic valve to be delivered via a catheter rather that surgically. A catheter bearing a new valve inside a collapsed metal mesh stent is inserted through the groin artery. It is pushed up into position in the heart, and when it is in place, a balloon inflates the stent, pushing the old valve out of the way. The balloon and catheter are removed, and the new valve takes over. TAVR is now a commonplace procedure.

Greenbaum used TAVR to replace Jenkins’ first valve, and Emory is approaching its 5000th TAVR this year. “TAVR marked the beginning of the shift from structural heart disease being a primarily surgical field to it being a primarily interventional field,” says Babaliaros.

Babaliaros and Greenbaum have taken TAVR to the next step. By electrifying a wire on the tip of the catheter, they can use a catheter not just to deliver a device such as a new valve but to punch through blood vessels and make incisions. They have modified the original technique to address several other structural heart defects.

One of those is hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, which impacted Jenkins. The condition impacts about 1.5 million Americans and can occur at any age. It is also the most common cause of sudden cardiac death in people under age 35 and is the main culprit in the sudden death of young athletes.

“Doctors Babaliaros and Greenbaum are pushing ahead in novel therapies that nobody else is even thinking of. All of this stems from their years of experience in a field they basically invented — transcatheter electrosurgery — with the help of their unique relationship with the NIH.” - Kendra Grubb, MD

“The heart muscles of people with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy are sort of like the arm muscles of weightlifters who can’t straighten out their arms because their biceps are so overgrown,” says Babaliaros. “When the heart muscle is so large and stiff, it doesn’t allow the left ventricle, which is the main pumping chamber of the heart, to properly fill with blood. This can result in difficulty breathing, heart palpitations or arrhythmias and chest pain.”

SESAME marks the first new non-pharmacologic treatment in almost two decades for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Until the mid-1990s, the only treatment for this condition was surgery to remove or make incisions in part of the overgrown muscle. Then a noninvasive treatment was introduced that involved delivering alcohol to a specific area of the heart muscle via catheter, causing that area to die.

“The field had become stagnant as far as procedural interventions,” says Babaliaros. “There just wasn’t anything new going on, so the field was ripe for an innovation.”

In the end, that innovation was propelled forward by Jenkins, whose painful, life-or-death health condition simply couldn’t wait, and who was courageous enough to trust her medical team to venture into the unknown if it meant getting more time.

Jenkins, who has gotten a new lease on life since the SESAME procedure, greets Greenbaum at a check-up in EUHM in May 2023. Jenkins’ daughter, Meri Pyle, looks on at the appointment.

Lederman, with the aid of two NIH colleagues, Christopher Bruce, MD, and Jaffar Khan, MD, developed the new technique and tested it on pigs. With the aid of advanced imaging techniques performed by Patrick Gleason, MD, Greenbaum was able to use the electrified wire to make precise incisions in Jenkin’s heart muscle to allow it to relax, which in turn allowed her left ventricle to fill more fully, establishing a normal blood flow. Since Jenkins, Greenbaum and Babaliaros have performed SESAME on more than 50 patients with promising results.

“A surgeon can only see one or two centimeters, but with the imaging we use, we can see the entirety of the muscle and we can cut anywhere, as deeply or as lengthy as we need to,” says Babaliaros. “The alcohol procedure causes an area of damage to the heart muscle, and often patients require a pacemaker afterward. SESAME does not result in any damage to the muscle, and we have only had one patient who has needed a pacemaker.”

All of the SESAME procedures to date have been done on a compassionate care basis for patients who had no other options, but Greenbaum and Babaliaros expect to begin a clinical trial in the near future, eventually comparing SESAME to surgical or alcohol ablation options.

“SESAME is a continuation of the transition that began from surgery to laparoscopic surgery,” says Greenbaum. “We’ve taken it a step further, from laparoscopic surgery to transcatheter procedures. We are able to use the patient’s bloodstream to get a catheter where we need it, electrify a wire at the tip and basically perform surgery. While early in its development with much still to learn, our vision is that 10 years from now, this will be the way most heart surgery is performed for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.”

Going forward

The Structural Heart and Valve Center undoubtedly will continue to innovate to meet the needs of their patients, including those who have been told they’re out of options.

“We are able to offer these patients literally what no one else can,” said Kendra Grubb, MD, cardiothoracic surgeon and surgical director of the Structural Heart and Valve Center. “Doctors Babaliaros and Greenbaum are pushing ahead in novel therapies that nobody else is even thinking of. All of this stems from their years of experience in a field they basically invented — transcatheter electrosurgery — with the help of their unique relationship with the NIH.”

For patients like Jenkins and her daughter Pyle, that means hope where there once was none.

“Mom is a totally new person,” says Pyle. “I have not seen her feeling this well since before her open-heart surgery. She’s out enjoying life again — walking and hiking nearly every day. I’ve got my mom back, and I couldn’t be happier.”