When vascular surgeon Vicki Teodorescu, MD, was growing up in a working-class part just outside of Newark, New Jersey, she said the standards for what girls like her might grow up to do were limited. “I don’t think there was much expectation for girls to do anything,” she said.

It was assumed that once young women graduated from high school, they would get married and have families, and “that was pretty much the end of that,” she said. But, from an early age, she felt called toward more. She wasn’t sure what, but she knew she needed to get out and explore.

It’s an inkling that had always been there — a hunch that she was destined to break out from that mold. Teodorescu guesses it came from her mother’s side — with their hardy, Scandinavian roots. Her ancestors immigrated from Sweden in the 1880s. During the long, arduous journey, her headstrong great-grandmother insisted that the family piano make the trip with them — across the water by boat and then across the prairie in wagons, dragging this several-hundred-pound reminder of home because it was an essential part of their family identity.

Dr. Vicki Teodorescu

One of her aunts, Mabel, had left the Midwest and ended up in Atlanta, attending college and making Phi Beta Kappa — not the norm for women in the 1920s. Taking a cue from Aunt Mabel, the minute she could, Teodorescu moved down the highway to New York City to kick off her almost cinematic-sounding path into adulthood.

First, she landed at the Fashion Institute of Technology, aiming to be a designer. And, although that might seem to be miles from her current role, “In retrospect, that was a great thing because they definitively taught me how to sew,” she said. “Even though I didn’t end up in fashion, it was a skill that worked out well.”

From the fashion world, she moved over to Wall Street, thinking that perhaps an MBA was in her future (interestingly, it was indeed her destiny — in 2010, she earned an MBA in healthcare from George Washington University). But back in her early career, working at an investment bank to underwrite bonds for city and state governments and other public entities that needed funding for parks, road repair, etc., something was still missing.

Since she had been a strong student in college and had an interest in helping people, Teodorescu decided to apply early acceptance to New York University School of Medicine — where she joined the graduating class of 1985, a cohort that she estimates was about 10% women.

Four decades later and, although diversity in medicine has increased incrementally, Teodorescu is still in the vast minority in her field. The current percentage of women vascular surgeons stands at about 15%, according to recent studies on gender disparities in medicine.

Once she started learning about medicine, something immediately clicked into place. Teodorescu gravitated to surgery for several reasons, including that it’s an awe-and-wonder-filled profession in many ways. Recalling some of the procedures she observed during her early training, she remembers thinking, “Oh my god, how could anybody survive this?” But they did and do. Watching how patients’ lives can transform so dramatically was “an amazing gift.” Vicki Teodorescu (left) and Kenya Thomas (right) at work in the operating room. Courtesy of Vicki Teodorescu

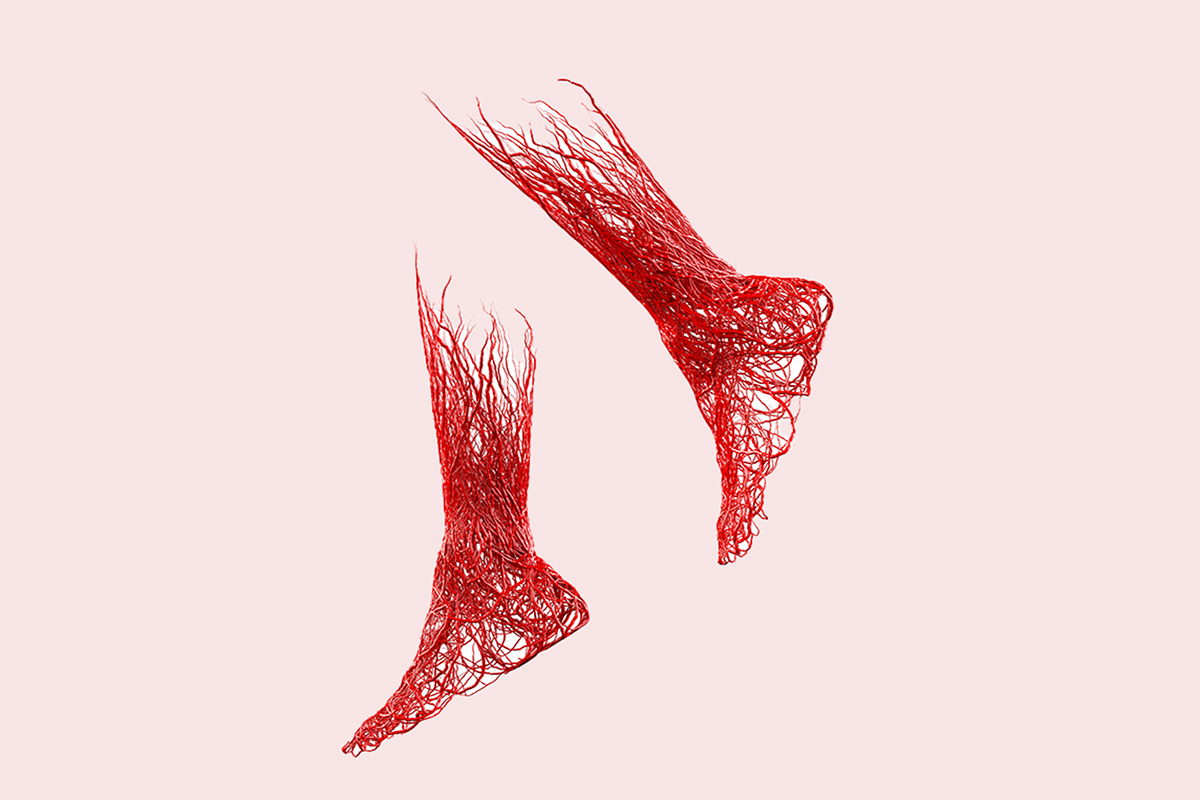

Vascular surgery drew Teodorescu in for similar reasons. “You go into the operating room and somebody whose legs are cold and kind of blue because there’s no circulation, and it’s painful,” she said. But then, “you reroute the blood, and you come out of surgery, and the foot’s warm and pink, and you can put your hand there and feel a pulse. To me, blood is the elixir of life, and if you can direct it, it’s miraculous.”

Teodorescu completed her general surgery and vascular surgery residencies at Mount Sinai Medical Center in 1991 and 1992, respectively, and then served several years as chief of vascular surgery at the Bronx VA Medical Center, where she instituted a diabetic foot clinic to combat emergency amputations for foot infection.

In 1998, she joined the vascular surgery faculty of Mount Sinai Medical Center. She served as medical director of the vascular laboratory from 1998-2003, chief of the section of vascular surgery at North General Hospital from 2005-2010, and program director of the vascular surgery residency from 2003-2010.

At Mount Sinai, Teodorescu collaborated with developing innovative bypass techniques for patients with severely diseased distal vessels.

She started to set her sights on Atlanta as a place to settle when her son, Alex, moved here to attend college at Georgia Tech (he graduated in 2001). Through frequent visits, she was struck by the sense of community and fun that surrounded not just the school but the city at large. “I said, ‘I can’t retire in New York. It’s too expensive, too cold. I don’t want to shovel snow anymore,’” she said. “And I really like it here.”

Finally, six years ago, she decided once and for all to make the big move to Georgia and applied to an opening at Atlanta VA Medical Center. But, although she didn’t get that job, her resume made it over to Will Jordan, MD, who had just started as division chief of vascular surgery at Emory — a fortuitous connect that landed Teodorescu right where she needed to be.

Now, on top of her surgical practice and teaching post at Emory School of Medicine, she enjoys spending quality time with her family and recently got hooked on cooking elaborate dishes to relax. Her most recent triumph was a Gordon Ramsey-inspired Beef Wellington this past holiday.

As for her surgical life, after all these years of practicing, it’s still a tough job sometimes. There’s the emotional weight that all surgeons face – the life-or-death stakes that can arise. Also, since many of Teodorescu’s patients may be living with chronic conditions, there’s often an element of only being able to treat, not fully cure, symptoms — which can be a challenge.

What keeps her going is the mission and charge of improving patients’ lives in tangible ways — where these mothers, uncles, grandparents, sisters, and sons can walk for longer without pain and sleep through the entire night without having to get up. “I find the smaller victories to be very satisfying,” she said.