Editor's note: Patrick Allitt is Cahoon Family Professor of American History. He teaches courses on American intellectual, environmental and religious history; on Victorian Britain; and on the Great Books.

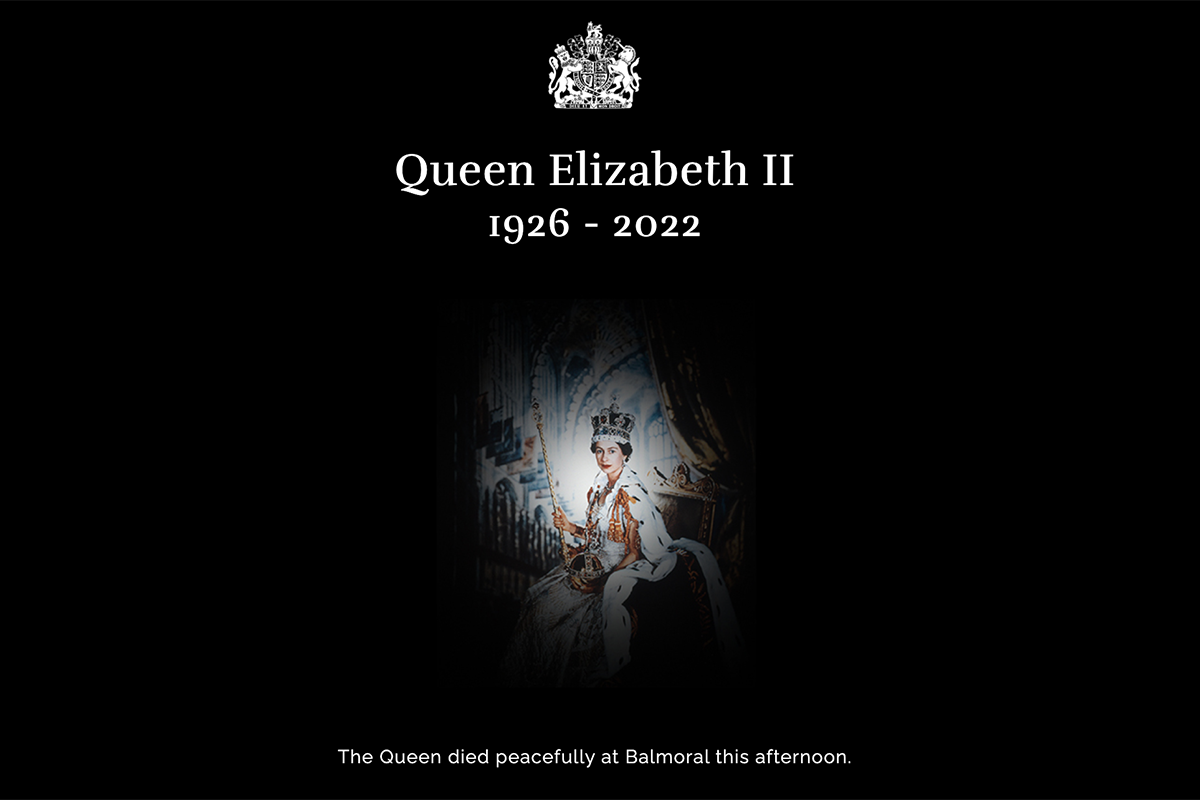

Queen Elizabeth II, who died on Sept. 8, was born in 1926 when Calvin Coolidge was president. The White House has had 16 different occupants since then. Being female she was unlikely to become monarch, especially as she was the daughter of the younger brother of the heir to the throne. But a succession of surprising events led to her accession at the age of 25, and she reigned for the next 70 years, becoming the longest-serving monarch in British history.

Emory historian Patrick Allitt was born and raised in Britain.

Like Victoria, her flinty 19th-century predecessor, she had a powerful sense of duty and was careful to uphold the distinction between herself as an individual and as head of state. She never took sides in political controversies; prime ministers from both the major parties could rely on her to voice the policies they favored when she spoke at the state opening of each Parliament.

She was one of the two or three wealthiest people in the world, enjoying unfathomable privileges. On the other hand, she had to endure pitiless and uninterrupted scrutiny from the world’s media, which became steadily less deferential with the passage of each decade. Her children had feet of clay. She was upstaged by Princess Diana and suffered sharp criticism in 1997 when her grief seemed, to many onlookers, inadequate.

None of the problems that confronted her, however, seriously dented her popularity, and many of them brought her renewed sympathy from people in Britain and around the world who could imagine her anguish.

She died as she had lived: dignified, regal and combining a queenly remoteness with just a hint of motherly affection. Her son now becomes King Charles III. She has bequeathed to him a constitutional monarchy of exceptional strength which, unless he makes catastrophic mistakes, will continue to enjoy widespread support from nearly all the British people.

I was born and raised in Britain so I’ve been hearing about the queen since early childhood. When I was five, at school for the first time, my class followed her route on a big map of North America as she traveled across Canada on an official visit. We were told that the queen was good, and that she headed the British Empire, which was also good. That was 1961.

Now I teach American history to American students. Nothing about America surprised me more when I first came here, in the 1970s, than discovering the American love affair with the British monarchy. After all, the United States fought a revolutionary war to get away from Britain; the second half of the Declaration of Independence is a detailed denunciation of King George III.

Somehow all that faded into the background after a generation or two. Just as Americans loved such well-known Britons as Charles Dickens, Charlie Chaplin and John Cleese, so many of them came to love the monarch too, and to refer to Britain as “the mother-country.”

Monarchs are, of course, easier to love when — as with Elizabeth II — their roles are mainly symbolic. Then they seem more quaint than powerful.