With a commitment to deepening a new and developing relationship, 15 Emory community members traveled to Okmulgee, Oklahoma, on a journey of learning at the invitation of the Muscogee Nation. Prior to Emory’s founding, the Muscogee people lived, worked, produced knowledge on, and nurtured the land where Emory’s Oxford and Atlanta campuses are now located.

While spending time with Muscogee elected leaders, educators and students, ceremonial leaders and community members, the group expressed Emory’s efforts to begin to understand, as President Gregory L. Fenves has said, “a more complete story about where we have been and who we are so we can build a more equitable, diverse, inclusive and vibrant university.”

The Emory students, faculty and staff who traveled to Oklahoma during part of spring break are members of the Indigenous Language Path Working Group, which Fenves appointed in November 2021 to fulfill a recommendation from the previous year’s Task Force on Untold Stories and Disenfranchised Populations to develop “physical reminders and rituals on campus that highlight Muscogee language and knowledge” as the original language and knowledge of this land.

But how?

Shared values

That question echoed 780 miles west of campus in Oklahoma, in the lands to which the Muscogee Nation were forcibly removed by the Trail of Tears in 1836, as the Emory delegation met with the president, faculty, staff and students of the College of the Muscogee Nation (CMN).

“At Emory, we want to embrace a spirit of accountability,” said Malinda Maynor Lowery (Lumbee), Emory College of Arts and Science’s Cahoon Family Professor of American History and co-chair of the Indigenous Language Path Working Group. “But frankly, we're not sure how to do that without the direction of the Muscogee Nation.”

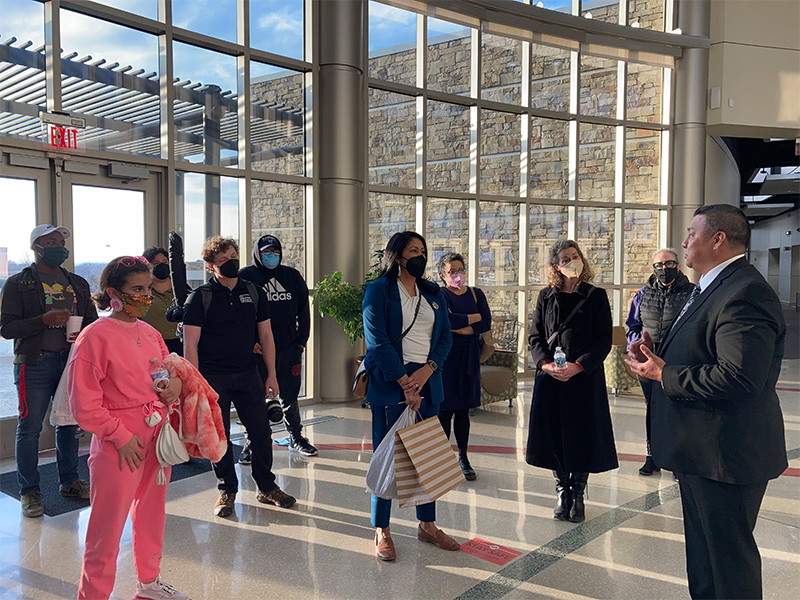

College of Muscogee Nation (CMN) President Monte Randall welcomes Beth Michel, Ciannat Howett and other members of the Indigenous Language Path Working Group to the CMN campus.

Over four days of educational gatherings, shared meals and gift exchanges, the Emory group heard recurring themes from Muscogee Nation members, whose 86,000 citizens comprise one of the largest Native tribes in the U.S. Some of the current priorities of the Nation, shared in a meeting with Principal Chief David Hill and Second Chief Del Beaver, were around education and health care, two deep values that the Emory community shares as well.

In addition, the Muscogee Nation hosts stressed the preservation of language and land, which are inseparable from their identity. Although they have been removed from Georgia for nearly 200 years, they have persevered as a people. What they are seeking today is the ultimate authority to preserve and pass on their ways of knowing and being.

‘A place of healing for us’

In 1821, the Muscogee moved west to Alabama after being forced to relinquish their remaining lands in Georgia, including what would become the campus for Emory’s Oxford College in 1836, and the land where Emory’s Atlanta campus is now located. More than 25,000 Muscogee Creek people were involuntarily removed in 1836-1837 from Alabama, and only approximately 14,000 lived in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) after the Trail of Tears.

The land where Emory now exists is for the Muscogee people a sacred place of healing, and invitations to return there, such as recent visits Muscogee Nation leaders made this past fall for Emory’s “In the Wake of Slavery and Dispossession” symposium and a visit that included a welcome reception and greetings from Provost Ravi Bellamkonda in November have been meaningful to the Muscogee people.

CMN instructor Mackie Moore (Cherokee), who traveled to Emory and other sites in Alabama and Georgia with tribal members who were experiencing it for the first time, noted, “The important thing is bringing people back there and acknowledging to those there that we still exist.”

“I've seen how important it is for our people to go back to those places,” he continued. “It's not [about] somebody saying, ‘We're sorry.’ It's about us going there to heal. Your place is a place of healing for us.”

CMN student William Bear (Muscogee) was in that delegation, and his first trip to Emory changed the way he viewed his own history.

“I never knew much about the mounds,” he said of sacred sites such as the Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park near Macon, Georgia, built by Muscogee ancestors. “Seeing all that helped me feel more connected to my culture.

“For a while, I had thought that learning the history we hear about our people was a very disheartening history. I like what you all are doing at your university for our language and acknowledging our homeland. You proved me wrong that there weren't non-Muscogee people who care about Muscogee people. So that opened me up too, and I'm very thankful to see other reputable institutions taking steps to help Muscogee people and our culture.”

The Mvskoke language

Emory’s growing attention to the Mvskoke language is meaningful, the hosts said, because the language carries forward Muscogee culture. “The Mvskoke language traveled 1,500 miles, through blood, death and tears,” Mvskoke Language Program instructor Rebecca Barnett told the delegation. “As speakers, we are the Atlas of the Nation. We hold it up.”

Honoring the language is an important entry point to honoring Muscogee people and lifeways, too. A high point of the trip was a special invitation the group received from The Rev. Chebon Kernell (Muscogee/Seminole), a United Methodist minister and Muscogee ceremonial ground chief, to visit his Helvpe Muscogee Ceremonial Grounds in Hanna, Oklahoma.

Mekko Chebon Kernell and his family welcomed the Emory Indigenous Language Path Working Group for a visit, conversation and lunch at the Helvpe Ceremonial Grounds in Hanna, Oklahoma.

Kernell’s daughter, recent college graduate Kaycee Kernell (Muscogee), felt moved to tears.

“By reaching out, I think you offer understanding that you all are … where our ancestors came from and are supposed to be recognized," she said. "I'd like to thank you for being here, for being rugged with us. It seems like by so many, we have been forgotten.”

Chebon Kernell stressed the importance of building this new relationship patiently, allowing it to grow organically, like the land itself.

At the same time, Emory’s land acknowledgment “has to mean something,” said Lowery. “There has to be an extension of reciprocity from Emory to the Nation as we are acknowledging this land that we're on. What can our new relationship look like?”

In September, Emory’s Board of Trustees approved an official Land Acknowledgment statement that honors “the Muscogee (Creek) people who lived, worked, produced knowledge on, and nurtured the land where Emory's Oxford and Atlanta campuses are now located" and announced Emory's commitment to humbly and continually "seek to honor the Muscogee Nation and other Indigenous caretakers of this land.”

Lowery described how this Land Acknowledgement and the idea for an Indigenous Language Path at Emory both developed from the work of retired associate professor of English Craig Womack (Muscogee), a leading figure in Native literary studies at Emory from 2009 until his retirement in 2021, who was part of the Task Force on Untold Stories and Disenfranchised Populations.

“Craig was really devoted to making sure that Muscogee knowledge was part of his classrooms in every way that he could, and so language was crucial,” Lowery said. “He co-taught language with people in the Muscogee Nation … and so from Professor Womack’s work, I think a sense of momentum has grown around Mvskoke language at Emory.”

Other key moments on the learning journey to Oklahoma included a visit to the newly opened First Americans Museum in Oklahoma City and the Greenwood Rising Museum in Tulsa, which present Native history and the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre through first-person accounts. The group was also invited to attend a meeting of the Muscogee Nation Youth Council and a wild onion dinner — a cherished spring tradition in the Muscogee community.

Emory College student Sierra Talavera-Brown (Diné), a member of the Indigenous Language Path Working Group, examined an exhibit at the First Americans Museum in Oklahoma City, which was designed and built by the 39 Native tribes now residing in the state of Oklahoma.

Next steps

Three Native students participated in the Emory journey: Sierra Talavera-Brown 23C (Diné), Isaiah Koiishe 25C (Pueblo of Laguna/Louisiana Choctaw) and Tre’ Harp III 25C (Muscogee/Choctaw).

Harp grew up in Beggs, Oklahoma, 13 miles from Okmulgee, and he described what the group is seeking to do through an agricultural metaphor.

“We are planting grass,” he said. “Now we are sowing the seeds and letting the roots sprout, and they're starting to be grass, and grass grows really slowly here. And we right here, the students, we are the tips of the grass. We're starting to take our culture with us and grow with it. We're branching out and spreading out even more like grass does.”

As the Working Group continues efforts toward the development of the Language Path, the next phase is reaching out and seeking input from the Emory community. To assist in this process, the Working Group has secured Kauffman & Associates, Inc. (KAI), a Native-led and women-owned consulting firm, to facilitate a campus engagement process. To begin, KAI visited Emory’s Oxford and Atlanta campuses for listening sessions in April; they will return Oct. 27-28 to continue community listening sessions.

“We are very excited to hear the thoughts of students, faculty, staff and alumni in this important work of establishing an ongoing relationship with the Muscogee Nation in Emory’s physical spaces and beyond,” said The Rev. Dr. Gregory W. McGonigle, Indigenous Language Path Working Group co-chair and Emory’s dean of religious life and university chaplain.

KAI will work with Emory through the fall in order to allow time for a deep engagement with students, faculty, staff and alumni from all of Emory’s schools and units. The main goal will be to develop a request for proposals by Nov. 15, 2022, to create a design for the Indigenous Language Path. That concept will include further research about Emory’s history and its relation to Native and Indigenous peoples and identify opportunities for future programming to educate the campus community.

Emory students, staff, faculty and community members gathered in Convocation Hall for an Indigenous Language Path engagement session on April 7.