Forty years ago, on June 5, 1981, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) carried a report of five otherwise healthy gay men in Los Angeles who suffered from a rare form of pneumonia. Two had died.

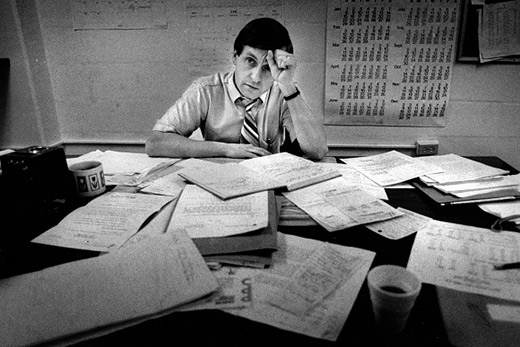

James Curran, an epidemiologist in the CDC’s Sexually Transmitted Disease Control Division at the time, was asked to review the report before it was published. That was his first glimpse at the disease that would roil the world and define his career: acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Soon after the report was published, Curran, now dean of Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health, was asked to chair a task force organized to investigate the cause of this unusual outbreak. He was detailed to the investigative team for 90 days. The assignment lasted 15 years.

The task force’s first order of business was to establish a case definition, determine how the disease spread, and develop prevention recommendations.

“In those early days it was all boots-on-the-ground surveillance,” says Curran. “We tried to identify and follow everyone who fit the description, which soon included other opportunistic infections and a rare cancer called Kaposi's sarcoma in addition to Pneumocystis pneumonia. We were trying to answer questions like, did these cases only occur in gay men? Were they limited to California and New York? Were they always fatal?”

Within weeks, Curran’s team confirmed more than 25 additional cases. The case definition the team put together based on their discoveries was adopted worldwide, allowing early and consistent recognition of the global AIDS epidemic.

It took two years for the cause of AIDS — a novel retrovirus eventually named human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) — to be identified.

Since then, vast progress has been made in diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Drugs developed at Emory — Emtriva and Epivir — are among the most widely used to suppress viral loads in infected people. The development of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) offered HIV-negative people effective protection from contracting the virus. Over the decades, AIDS went from being a death sentence to a chronic, life-long condition that could be managed with the correct medications.

In 1995 Curran left the CDC to become the dean of the Rollins School of Health, but he continued working in AIDS as co-director of the Emory Center for AIDS Research (CFAR). On the 40th anniversary of the first published account of AIDS, he reflects on the progress that has been made and what lies ahead.

“We’ve come so very far, yet there are about 38 million people worldwide living with HIV,” says Curran. “It’s a silent disease, so there are many more than 100,000 people in the U.S. who are infected but don’t know it. We’ve been able to reduce mortality and slow the transmission rate, but current therapy is not curative and must be continued for life. We can’t talk about totally eliminating AIDS until we’ve developed a vaccine and curative therapy. These remain important priorities for our current CFAR scientists.”

Still, the history of AIDS offers positive lessons. Though the beginning of epidemic was characterized by fear and homophobia, with President Ronald Reagan refusing to speak publicly about AIDS for nearly six years, a commitment to fight the disease prevailed. The George W. Bush administration established the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) to bring relief, including heavily discounted drugs, to Africa and Asia, which suffered disproportionately.

“That global philanthropic commitment has saved tens of millions of lives,” says Curran.

Governments would do well to heed this lesson, especially in the face of wealthier nations hoarding COVID-19 vaccines.

“One thing AIDS taught us, and subsequently Ebola and Zika: Pathogens do not respect national boundaries,” says Curran. “If we want to keep ourselves safe, we have to keep everyone safe.”