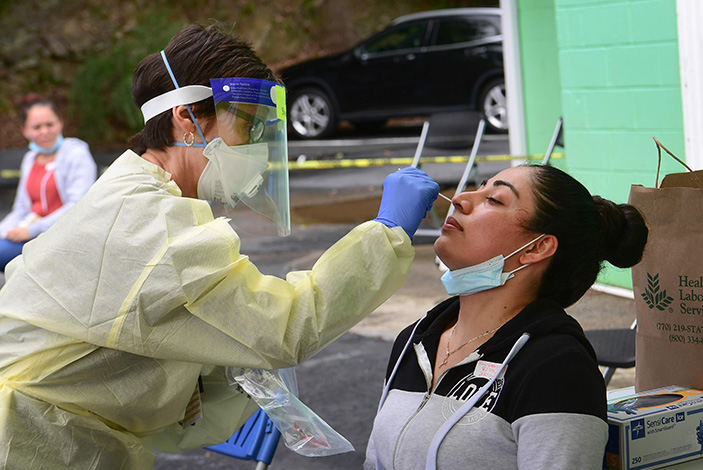

It’s a sunny morning when epidemiologist Jodie Guest and eight graduate students from the Rollins School of Public Health arrive at a parking lot in North Georgia. Each pulls on a full suit of personal protective equipment (PPE), making them nearly indistinguishable inside their de rigueur pandemic uniforms — gown, mask, gloves, plastic face shield and hairnet.

There isn’t much time for small talk as they settle in under portable shelters stocked with vials and swabs. Guest checks her team’s PPE and confirms everyone is in place before a long day of testing begins.

The group is about an hour’s drive north of Emory University, where they study and work. But here, in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, they are on one of the newest front lines in the fight against COVID-19. As the virus shows signs of ebbing in some hard-hit urban centers, it is flaring in rural pockets of the country, where rates of poverty are high and health care resources scarce.

One of those outbreaks is here in Hall County, where so many chicken plants dot the landscape that the county seat of Gainesville calls itself the “Poultry Capital of the World.”

Providing public health assistance is the goal of a new partnership between Rollins and the Georgia Department of Public Health. Launched with a $7.8 million grant from the Robert W. Woodruff Foundation, the Emory COVID-19 Response Collaborative (ECRC) is designed to bolster response and surveillance efforts all around Georgia.

Kathleen E. Toomey, MD, MPH, commissioner of DPH, said protecting Georgians from COVID-19 requires a partnership between public and private sectors.

“There must be ample and accessible COVID-19 testing, extraordinary community engagement and an ability to trace contacts of new COVID-19 cases in order to forestall resurgent outbreaks,” Toomey said.

Guest, PhD, MPH, vice chair of Rollins’ department of epidemiology, is part of the collaborative. She was tapped to lead the response in Gainesville before the new project was announced but it is proving to be a model for what some of their work will look like moving forward.

“We are putting boots on the ground,” Guest says. “The aim is to be nimble and learn where the needs are in the communities we support while building trust. We want to determine the extent of infection in this high-risk community, gauge awareness of the need to take precautions, and explain to families how they can remain safe and well during the pandemic in ways that are culturally sensitive and easily accessible.”

Reaching rural communities

Poultry plants have been deemed essential during the pandemic because of their key role in the food supply chain. But rising infection rates among plant employees have alarmed public health officials, who worry that the close working conditions make poultry workers particularly vulnerable to COVID infection and the likelihood for rapid spread of the disease high.

There are inherent challenges in reaching these underserved rural communities. Guest knows those challenges well. She currently leads the Emory Farmworker Project in South Georgia after participating in it since 2007.

The agriculture industry is enormous in Georgia. Even as Atlanta and other urban areas have grown in size and influence, agriculture remains the single largest engine of the state’s economy.

Every year tens of thousands of farm workers come to Georgia to work the state’s plentiful crops — Vidalia onions, tomatoes, blueberries, pecans and peaches, to name a few. Many of the workers are itinerant, moving from place to place in a rhythm dictated by the harvest cycle.

At the chicken and meat processing plants, workers tend to be more settled. But beyond that, the barriers to health care outreach are similar. Many speak only Spanish and reading levels are minimal with children often serving as interpreters for their family. These workers often reside in crowded, multifamily homes where social distancing is nearly impossible. Then there is a lack of access to health care and insurance.

“This is a marginalized population, an unseen population,” she said.

Testing and education

More than 40 percent of the population in Gainesville is Hispanic, according to recent Census figures. Guest has been working with school districts to distribute prevention materials in Spanish, with a heavy focus on graphics.

“The best public health messages do not work if they cannot be read,” she said.

In Gainesville, she said, the approach is two-pronged – testing and education.

Guest and her team ride the school buses that are bringing breakfast and lunch to children. By connecting with this established and trusted distribution system, they hand out masks and prevention messages they have incorporated into coloring pages and picture-filled newsletters to explain the importance of social distancing, wearing a mask and testing.

On their recent May 22 visit, they were providing tests at Vital Foods, one of Gainesville’s many chicken plants. A steady stream of workers at Vital Foods filed through the makeshift testing center in the parking lot that was one minute in the beating sun and the next in a storm that whipped tents over.

Juan Carlos Llomas, CEO of Vital Foods, welcomed the fleet of public health workers.

Already, Llomas said, employees were wearing face masks and spreading out in the plant; equipment was being sanitized. But workers were still scared. And with just under 400 employees at two plants, a single asymptomatic carrier could infect large swaths of other workers, conceivably bringing the whole operation to its knees. This is why he connected with Guest and her outbreak team to bring testing directly to his company.

“We wanted to have a safe environment for our employees,”Llomas said. “They aren’t afraid to go to work now. This is good for our employees and good for our company.”

Over three days, Guest and her team tested some 450 workers as well as their family members and other contacts. Roughly 25 percent tested positive and were notified after the results came in a few days later. That’s more than double the statewide and national testing averages for COVID.

Llomas said workers who tested positive were paid while they quarantine at home and could return to work after testing negative.

As part of the effort, the Emory team was also working to validate whether a new saliva COVID-9 test and an anterior nares swab worked as well as the standard nasal swab. These newer testing modalities are less invasive, require less PPE and can be self-administered. Each worker who arrived was tested with the standard clinical test and one of the research tests to see if the results matched. Guest said early results are very promising.

Despite the demand of the work, Guest and her team also found time for a little fun, posting a video to Tik Tok where they busted out some dance moves to The Weeknd’s “Blinding Lights.”

Guest said she is looking forward to taking the lessons learned ]in Gainesville and applying them in other areas of Georgia where the need is also high.

“I hope a benefit to come out of this pandemic will be a focus on fixing the systemic inequities that have placed excess risk with some of our most vulnerable populations,” she said.