In his 2012 Distinguished Faculty Lecture on Feb. 6, Harvey Klehr confided to the audience in the Winship Ballroom: "Having devoted my career to studying a marginal political movement, the Communist Party of the United States, I often feel compelled to justify what I do."

Emory's Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Politics and History, whose lecture, "Me and Joe McCarthy: Studying American communism," was part of Founders Week, noted that "to be obsessed with groups and ideas that have failed so consistently and spectacularly" was an odd choice of a research topic for his over 40-year career.

After all, "The United States is the only major industrial nation in the world where no socialist or communist movement or party has either come to power or seriously contested for power," he said.

"So why devote one's intellectual life to studying failures?"

He answered, "The fate of the American left touches on of much wider things that go to the heart of still-heated debates about the nature of American society.

In spite of its political failure, the Communist issue dominated American politics from the end of World War II to the early 1950s."

Despite its small size — the American Communist Party (CPUSA) enrolled no more than about 90,000 members at the height of its influence — the CPUSA aroused very strong passions.

Klehr traced the scholarly zeitgeist of American communism from the 1970s, paralleling it with his research, which was going against that grain. To many of the new researchers, "the Communist party had become an object of nostalgia and sympathy," he said, a small inoffensive group of idealists committed to democracy, labor organizing and civil rights. That the American government had vastly overestimated the threat of Soviet espionage was widely supported.

Klehr found himself labeled a "McCarthyite," taken from the investigations in the early 1950s by Republican Sen. Joseph McCarthy of alleged Communist infiltration into the U.S. government — a label he described as a "scurrilous and unwarranted accusation" suggestive of being engaged in sleazy maneuvers.

Nothing changed the study of American communism more than the collapse of Soviet Union and the opening of Russian archives, he said. In that treasure trove, he found that the CPUSA had periodically shipped all its records to Moscow for safekeeping. Because Klehr's research up to that time had been based on limited original sources, he was concerned what he found might force him to repudiate it. "New archival material overwhelmingly confirmed my positions," Klehr said. "The revisionists had been wrong."

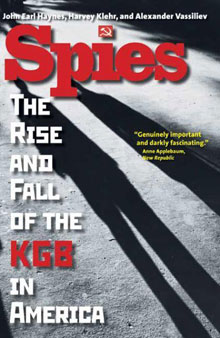

The new evidence Klehr and his author-colleague, John Haynes, found provided extensive evidence of massive Soviet funding of the CPUSA from formation into 1980s. It also yielded scores of top-secret documents about the CPUSA's deep and intimate ties with Soviet intelligence agencies and espionage.

Still, Klehr warned, the new evidence does not vindicate McCarthy, a man who gave his name to an era in American history rife with paranoia and fear, a man who went on a witch hunt.

"Like Joe McCarthy, I'm obsessed with communism — not to score political points but to remind my students and my colleagues that in the 20th century the United States defeated two tyrannical and evil systems.

"Any academic expressing nostalgia for Hitler or sympathy for Nazism would be a moral pariah in American higher education. It is long past the time when the same standard was applied to defenders of communism. That is not McCarthyism but fidelity to democratic and humane values."