ATLANTA - In recent weeks, three Emory University experts in critical care medicine and infectious diseases have been at the center of a national effort to establish comprehensive federal guidelines on the care of patients with COVID-19.

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines, which were released by the National Institutes of Health on Tuesday, April 21, include treatment recommendations for patients at all stages of illness severity, as well as for those who are not infected.

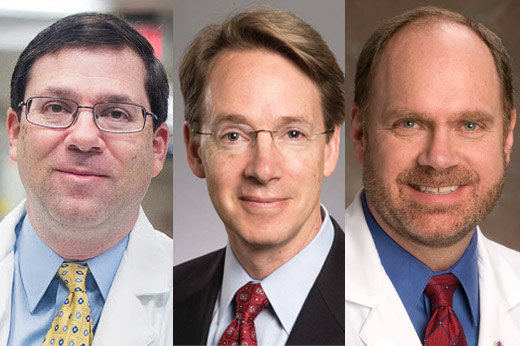

The three Emory doctors involved in the project were among 29 experts from across the country who spent the last several weeks sifting through published studies, reviewing the data for a broad range of drugs that have been touted as effective treatments and comparing strategies for managing the illness in a critical care setting.

“For decades, Emory has been at the forefront of treating infectious diseases, implementing clinical trials and developing protocols for treating critically ill patients,” says Greg Martin, MD, MSc, professor in the Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine at Emory University School of Medicine and committee chair for critical care at Grady Memorial Hospital. “We are fortunate to be in a position to bring our expertise to bear in helping develop these guidelines for treating patients with COVID-19.”

Martin participated in the group on treating patients in a critical care setting. Craig Coopersmith, MD, professor of surgery and interim director of the Emory Critical Care Center, participated in the group on severely ill patients and the use of potential therapies to modify the immune response such as immunomodulators and disease-modifying medications. Jeffrey Lennox, MD, professor of medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Emory, helped to lead the group focusing on mild to moderate patients and the use of antiviral therapies in patients with COVID-19.

The ongoing pandemic has led to a surge in published case reports and studies as the medical research community worldwide has turned its attention to trying to understand COVID-19 and how to treat it. Part of the goal of the new guidelines is to distill the growing amount of research into a single resource that can be updated as scientific understanding as the illness evolves.

“When you see a study or case report out in the public domain mentioned without context, it is very hard for someone to ascertain whether it is legitimate or safe,” Martin says. “These guidelines represent an effort to create a resource that people can rely upon, informed by a critical review of the evidence we have to date.”

The group of experts split into four groups to develop clinically important recommendations that address potential therapies and encompass all patient types as well as special populations, such as pregnant women and children.

For the critical care group, Emory’s experience in treating patients in that setting provided a framework for the recommendations for managing treatment for critically ill patients with COVID-19.

“Emory has decades of experience treating similar conditions in a critical care setting that are now being used as a model for the care of COVID-19 patients,” Martin says. “We’re at the leading edge in developing and applying the current evidence on how you should manage a patient with COVID-19. You need to pay attention on how to use a mechanical ventilator, how you manage shock, and how to manage other cardiovascular, hematologic and neurologic complications of COVID-19. These are the foundations of Emory’s protocols.”

Coopersmith’s group spent much of their time discussing the evidence for using host-modifying agents to help combat the body’s immune response to COVID-19.

“For COVID-19, there is not yet any evidence that we can effectively manipulate the host immune response in a way that benefits the patient,” Coopersmith says. “When a patient is infected, it is not just the microbe itself that is causing the problem. Rather, it is a combination of the pathogen, and their own body’s response to the infection.”

Coopersmith, an expert on sepsis and the body’s response to such an infection, said his group reviewed small studies and case reports on the use of medicines that would modify the body’s response to the infection. Despite a high number of anecdotal published case reports, the group found insufficient data to recommend for or against the use of some such “host-modifying agents” outside the bounds of a clinical trial. For other drugs, the group expressly recommended against their use outside of a clinical trial.

“The reason we do randomized clinical trials is that outside of that structure, you don’t know how a patient would have done if you had not given them to drug,” Coopersmith explains. “It is incredibly important that efforts to test these drugs be directed into the framework of such a trial. Unfortunately, there is a long history in critical care of trying drugs that had a plausible biological rationale that turned out to be ineffective or even harmful. So even in the time of a pandemic, it is important to rigorously weigh available evidence in order to treat patients with therapies whose benefits outweigh their risks.”

Lennox, who is co-director of the Emory Center for AIDS Research Clinical Research Core, participated in a group that was tasked with reviewing the use of several antiretroviral drugs that are used for HIV patients. Their group also recommended that such drugs not be used outside of a clinical trial.

“Many of these medications can have potentially life-threatening drug interactions that need to be understood whenever they are prescribed,” says Lennox. “Until there’s sufficient evidence to show that these drugs can be efficacious against COVID-19, we believe they should be used only in a clinical trial.”

The guidelines will be updated regularly as new recommendations are made.