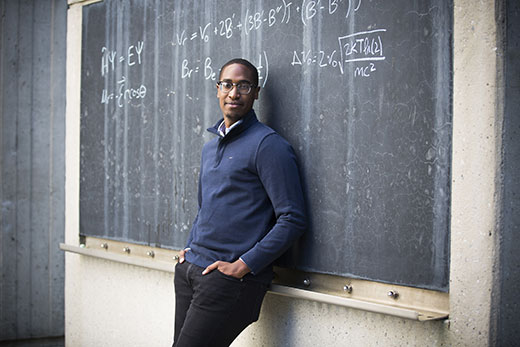

If Samuel Zinga were a sports prodigy, he would have turned pro in high school.

That’s when Zinga began dominating his court of choice — the chemistry labs of Emory College of Arts and Sciences.

Now he’s graduating from Emory with highest honors, headed to Yale University School of Medicine for a yearlong appointment studying antibiotic resistant bacteria using advanced light microscopy techniques. He plans a joint MD/PhD program to follow.

But like any true superstar, Zinga’s impact has been even greater out of the spotlight: Zinga leaves Emory after building up an education pipeline for refugee, immigrant and low-income students like him. His planned career as a doctor/biomedical researcher also will focus on the same population.

For his commitment to put in the work to supplement his natural talent, while making time to pay it forward, Zinga has earned the highly selective McMullan Award for 2019.

The award, made possible by a generous gift from Emory alumnus William Matheson 47G, recognizes Emory College graduates who show extraordinary promise for future leadership and rare potential for service to their community, the nation and the world. It also includes $25,000 to be used in any way Zinga chooses.

“Sam is the sort of student I could easily see curing cancer or solving world hunger, or both,” says Susanna Widicus Weaver, associate professor of chemistry, who has known Zinga since he was a junior at the nearby Gwinnett School of Math, Science and Technology, which has a partnership program with her department.

“He is excited about science and passionate about giving back, and he does both exceptionally well,” she adds. “He’s amazing because he makes it look easy.”

Helping others learn

Zinga has known struggle. But he credits those who supported him through those hurdles for his accomplishments.

First are his mother Joujou Ndenga and father Gaby Zinga. His Rwandan mother was a target – as was he – when Zinga was born in the Democratic Republic of Congo during its civil war. His mother and Congolese father fled to Cameroon before being granted refugee status in the United States when Zinga was three.

In doing so, his parents traded professional careers for hourly work in the hope of creating opportunities for their children. They also had to learn English, which was not one of the four languages they spoke. They, along with Ndenga’s sister and her young child, learned it by listening to Zinga when he returned from his pre-K program and talked to his year-old sister.

As they navigated their new country and Zinga completed first grade at International Community School in DeKalb County, he took note of the volunteers working with him and his family and made himself a promise.

“I’ve always known that when I could, I wanted to be the one helping other refugees, immigrants and people in low-income communities,” he says. “I wanted to share the support we got when we needed it.”

In high school, Zinga began volunteering to help incoming refugees set up apartments. He also started a program to help younger high school students in their courses.

Although he tutored in everything from computer science to English, he was especially interested in helping other students with their science homework.

“Whether it’s your body or space, every branch of science is about trying to explain how things work,” says Zinga, who was enamored with the subject as early as he can remember. “I wanted to get someone else as excited about that as I was.”

That excitement jumped out at Widicus Weaver when she reviewed the single-page resume Zinga submitted as part of his AP chemistry class’ partnership with Emory.

She was adamant about having him work in her astrochemistry lab, where she and her researchers often must build their own equipment to hunt for the molecules that help understand chemistry in space.

Zinga didn’t disappoint. He was eager and humble, even as he built his spectrometer out of spare parts the next year, before he officially entered Emory.

“Sam is truly one of a kind,” says Shiv Patel, a senior neuroscience and behavior biology major who has been Zinga’s friend since the two met in the pre-orientation program now known as STEM Pathways, that guides and supports students who are the first generation college students, or who are members of groups that are underrepresented in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) careers.

“I’ve never met someone as knowledgeable, as sociable and as friendly as Sam,” Patel adds.

Connecting Emory to the community

In many ways, Zinga sought a typical college experience, or at least how it’s done at Emory. The liberal arts coursework meant he could continue to excel in science classes, dive deeper in the astrochemistry lab and also explore his heritage in a music course by researching the inanga, a stringed instrument played in Rwanda.

He is a musician as well, playing bass in the Emory University Symphony Orchestra for three years and occasionally playing guitar and singing on campus in a performing duo with a friend, senior Kathy Li.

He also jumped back into volunteering. Zinga tutored undocumented students on SAT and ACT prep through Volunteer Emory and also began working with the Fugees, a soccer team turned school for refugees in Clarkston.

By his sophomore year, Zinga was helping adults and children alike through Project SHINE, Emory’s signature engagement program with Atlanta’s refugee, immigrant and new American communities. One of his earliest project sites was at his one-time school, International Community School.

His devotion helped Project SHINE grow 65 percent in the past few years, in part by recruiting some of the students he tutors on campus as a ChemMentor and with STEM Pathways.

“Although he won’t talk about it much, Sam has been such a gift in connecting Emory to the community,” says Johannes Kleiner, associate director of Civic and Community Engagement, the Campus Life office that houses Project SHINE. “There is no better representative for Emory. He is a genuine role model.”

If Zinga wants other refugees and immigrants to see themselves in him, one of his most meaningful memories is seeing something familiar in them. Specifically, he was touched by how appreciative the adults were in his class covering advanced English grammar and spelling. They reminded him of his parents.

“Their reason for learning English was to support their families. For me to help with that … ,” he says trailing off with a smile and shake of his head.

Zinga carries his identity as role model for other students of color, especially first-generation men of color. After working with Emory Residence Life since his second year on campus, he was hand-selected [specifically chosen] as one of the resident advisers for the Black Male Initiative, a learning community launched this year designed to support first-year black male students.

“I want their experience at Emory to be meaningful,” Zinga says of his work. “A lot of my involvement is just recognizing a need and seeing what my part is in helping.”

Planning to give back

Antonio Brathwaite, a senior lecturer in chemistry, saw that mindset in action when Zinga was in his physical chemistry laboratory course, traditionally challenging even for talented students because of the intensive math and complex quantum mechanics.

Brathwaite tapped Zinga to be a peer leader, helping others in the class grasp the concepts. He watched Zinga exhibit similar patience and passion as a ChemMentor, where he advised first-generation and underrepresented students in review sessions hours after class had ended.

“He’s destined for greatness, and he is humble on top of it all,” Brathwaite says. “He has the potential to do whatever he wants.”

Zinga decided his path in part after talking with Brathwaite, who recommended him to the Yale School of Medicine research program last year.

In typical fashion, Zinga exceled to the point of presenting a poster on his work at the Annual Biomedical Research Conference for Minority Students last fall and earning the research job he starts after Commencement.

He also made time to take the MCAT – Brathwaite notes he was two points shy of a perfect score on the difficult exam, putting his score in the 100th percentile – and to talk to other researchers before deciding to make his specialty infectious disease.

“With infectious disease, I can look at the refugee community at both a macro and micro level, treating patients in a clinic for what my research could address on a broader scale,” Zinga says.

None of it would be possible without those who mentored him and helped him build the confidence to pursue his dreams, he says.

“It’s been a sense of motivation for me, knowing my parents worked so hard to provide for us, having mentors who matched my excitement to learn with their willingness to teach,” Zinga says.

“I’ve always known I would give back,” he adds. “Outside of being rewarding, it gives me energy to help my communities.”