For nearly a decade, the Emory-Tibet Science Initiative has done more than challenge the idea that religion and science don’t mix by developing and successfully launching a comprehensive science curriculum for thousands of Tibetan monks and nuns.

The first major change to Tibetan Buddhist monastic education in six centuries also demonstrated how insights and information from both the monastics and professors could enrich each other’s understanding of biology, physics and other sciences.

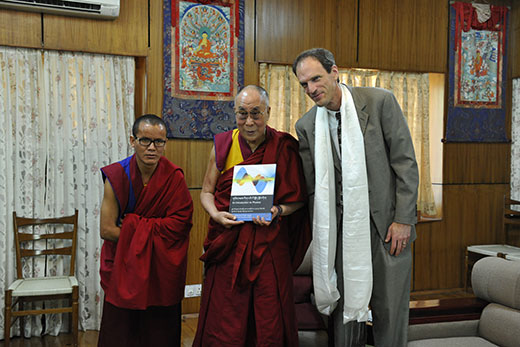

Arri Eisen, an Emory College professor of pedagogy in biology and the Institute for Liberal Arts, explores those connections in “The Enlightened Gene,” a book he co-wrote with one of the monks, Geshe Yungdrung Konchok.

“He grew up on the Tibetan plateau herding yaks. I grew up one of about five Jewish guys in North Carolina in the 1970s,” Eisen says. “We had different experiences, but we could use them to develop a common approach, to try to better understand our world.”

Emory has woven Western and Tibetan Buddhist intellectual traditions together since founding the Emory-Tibet Partnership in 1998. His Holiness the Dalai Lama has been a Presidential Distinguished Professor at Emory since 2007.

Serving a community in exile, the Dalai Lama has been charged not only with keeping spiritual traditions alive, but cultural ones as well. He invited Emory to form the Emory-Tibet Science Initiative (ETSI) in 2007, as a long-range project to exchange Buddhist cultural and intellectual wisdom and cutting-edge scientific knowledge.

The first two cohorts of 77 monks and nuns completed their five years of summer education in 2012 and 2013, respectively, and have since gone off to monastic academies to share their newfound knowledge – and how it ties to traditional beliefs.

“When we studied evolution, we learn from a scientific point of view, we all share a common ancestor,” says Geshe Dadul Namgyal, a Tibetan monk who serves as an ETSI translator and interpreter. “That is very powerful to us, because it is a scientific concept that goes deep into our belief that all sentient beings are connected.”

Some Buddhist traditions have helped anchor the project, Eisen notes. Buddhists embrace all worldviews, to better understand their own thinking. Likewise, Buddhist teachings are available to all seekers, without conversion.

Integrating biology and Buddhism can be deceptively simple at times, Eisen found, while addressing some of the larger questions of what it means to be human.

In some of his initial teaching, Eisen observed that monks struggled at first with the basic concept that living things are made of cells. As Namgyal explains, all living beings have minds and bodies to Buddhists, different words that made “cells” a difficult concept to students wondering if bacteria feel pain.

But such innovative thinking is exactly what science needs, Eisen says, if only because the best discoveries and learning come when people are able to identify points of tension within a subject.

“In the West, it has been accepted that anything science can do, you do it,” Eisen says. “Buddhist thought asks what does this involve and who decides what we do. It goes to the heart of the ethical questions that have become more important as science advances.”

The book reveals the community of neuroscientists and monastics connected by their interest in the mind and body, whose points of view can affirm and challenge each other.

For instance, the growing understanding of the “gut microbiome” — the cluster of intestinal microbes thought to help regulate the immune and nervous systems — can also be viewed as an illustration of the spiritual concept of coexisting, sentient life.

“On the large scale, integrating science and faith changes the way we think about science and therefore some of the big scientific questions,” Eisen says.

“An amazing side effect is learning that scientific thought should meet people where they are at, either as a room of undergraduates with diverse backgrounds or a class of Tibetan monks,” Eisen says. “Understanding the science of the things we care about is what makes science alive.”