Hiram Maxim watched during the presidential campaign last fall as critics on both sides of the ideological aisle began comparing the opposing candidates to Hitler.

When Donald Trump won and detractors labeled him a “fascist” and likened his early Cabinet picks to Nazi Germany, the German Studies professor worried: The terms were used too freely and lightly without necessarily any clear understanding of the realities of fascist Germany.

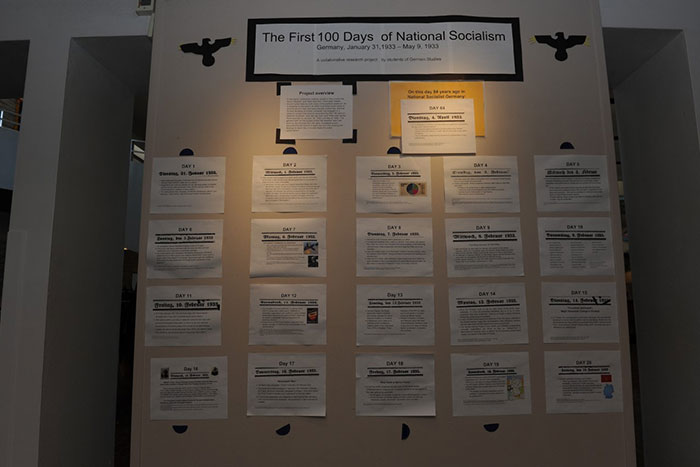

As it turns out, many Emory College students were having the same debate. When Maxim emailed students about a directed studies course to examine the issue, “The First 100 Days of Fascist Germany” was born. The general idea is to document each day’s events for the first 100 days from when Hitler was named Reichskanzler on Jan. 30, 1933, until May 9 of that year.

“There is a role for German Studies and the liberal arts to step in and make sense of these comparisons,” Maxim says. “In the end, we accurately document what happened 84 years ago, rather than commenting on today. We want to inform students and the general public on the facts they are claiming.”

The project participants publish their work daily online, via Twitter and also through a poster display inside the Dobbs University Center.

Students began work in February, researching primary sources to reveal the daily happenings during the first weeks of National Socialism. Detailing major events challenges the students not only in their understanding of German and history, but also in their ability to apply their technical skills to build a website and create software to help their digital research.

A handful of the students are even volunteering for the project, so engrossed in the topic that they want to participate even though they aren’t receiving credit.

“This is a great learning experience, to see Hitler’s rise and understand he had a plan all along,” says Allison Rose, a sophomore statistics and music major enrolled in German 102, who built the project’s website in a burst of excitement after the first meeting. “It’s been eye-opening to see how quickly it moved.”

It was on Day 51, for instance, that Dachau opened.

Hitler’s Police President Heinrich Himmler initially described the concentration camp as only for political prisoners — namely anyone deemed an enemy of National Socialism — but it became the site of 32,000 documented deaths at the time of liberation in 1945.

By Day 60, the president of the German Newspaper Publishing Association demanded that wire services and international news organizations halt “inflammatory” news about Germany. Effectively, no publication could criticize Hitler or National Socialism.

“In a lot of ways, seeing that shows how people give Hitler much more credit than he deserves, because you see how his party and people and German society were complicit,” says Tyler Willrich, a junior anthropology and political science double major, who is enrolled in German 102 and working on the project.

“Personally I think because American culture is much more comfortable criticizing authority, you can see that’s one parallel that breaks down,” Willrich adds.

Providing context, not conclusions

Researching and understanding those potential parallels has been a time-consuming process. It took students several weeks to be caught up to publish each day with that day’s events from 84 years ago.

Willrich helped speed things along by configuring optical recognition software to convert the Gothic typeface from a main resource — digitized copies of the daily newspaper Berliner Morgenpost found on the German Press Museum website — into something easier to read. Still, even in a more legible font, the words challenged the students, many of whom are in their first year of German language study.

Sophomore Haley Gast is enrolled this term in German 102 and works with other students to translate and make sense of the world eight decades ago.

The political science and German studies major, who plans to study abroad in Vienna this summer, says she can see shallow parallels from the rise of Hitler to the current climate.

Nazis, for instance, did not win an absolute majority of the vote in the multi-party election on Day 34, just as Trump did not win a majority of the vote in November.

The systems, however, do not compare, Gast says. Trump did have a clear win in the American two-party system, with the Electoral College. Meanwhile, the election results in 1933 necessitated the formation of a coalition with other parties to govern, but National Socialists instead changed the rules so that they no longer needed partners to pass law.

“We’re not trying to convince anyone of any conclusions,” Gast says. “I think it’s important to contextualize what happened in Germany, to understand specifically what the Nazis did, because by establishing just what those terms mean, and what they did, we can more accurately describe what we’re seeing now.”