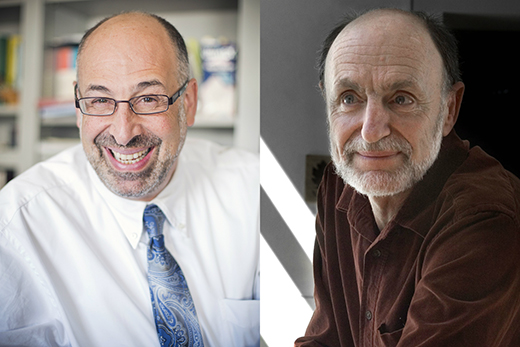

As a global specialist in eco-epidemiology, Uriel Kitron is immersed in a complex world of insects and infectious diseases, maps and geography.

With a long-held interest in the construction of national identity, historian Jeffrey Lesser's research is rooted in the realm of ethnicity, immigration and race, with a special emphasis on Brazil.

This semester, the Emory power duo is combining those research strengths, teaming up to explore how the dynamics of human migration, disease transmission and access to health care have impacted a vibrant immigrant neighborhood in São Paulo, Brazil — one of the world's largest megalopolises.

Their joint research project, "Metropolis, migration and mosquitoes: Historicizing health outcomes in São Paulo, Brazil," not only marks an ambitious first-time collaboration for the pair, it's one of three research proposals selected to receive the 2015 Interdisciplinary Faculty Fellowship through Emory's Institute for the Liberal Arts (ILA).

The project will explore how discourses about health and urban populations over time affect transmission of mosquito-borne diseases — such as yellow fever, dengue and Chikungunya — and access to health care from the beginning of the 19th century to now.

By spring of the 2016-2017 academic year, the project will also be expanded into a for-credit course available to Emory undergraduate and graduate students, with additional student research opportunities in Brazil for qualified applicants.

Examining disease through "the eyes of each other"

Lesser and Kitron discussed their project in a recent interview, conducted via video while both were in Brazil. When asked how scholars from seemingly disparate academic disciplines found a common research focus, they laughed.

"Well, when two intellectuals sit together and ruminate about the nature of the world long enough…" joked Lesser, Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor of History and chair of the history department.

"Actually, Uriel and I are both department chairs," he explained. "Eventually, you get to know your colleagues from other departments, and we discovered that we were both doing very different research in Brazil — Uriel works on the ecology of infectious diseases and I work on the cultural history of identities."

But both researchers shared an important goal. "We are at a point in our careers where we were wanting to do something new, to really take some risks, to not be obsessed with the conventional…" said Lesser.

"…And we were interested in employing our disciplines in a non-traditional way," added Kitron, Goodrich C. White Professor and chair of the department of environmental sciences.

So they started talking, floating ideas that would not only employ their own research in a different direction but also provide an opportunity to "learn new methods from each other," Lesser said.

"We didn't want something where it was 'he does half and I do half,'" he said. "In this project, we both do everything."

One day, that means poring over documents about neighborhood ethnic groups or poster campaigns against mosquito-borne illnesses in a national health archive. The next day may be spent collecting water and mosquito samples, he said.

"The exciting thing is that we are looking at the history of infectious disease in a neighborhood through the eyes of each other," Lesser noted.

Brazil: A natural laboratory

It helped that from the beginning, Brazil was a natural intersection. "We both spend time in Brazil already," said Kitron, who was awarded a fellowship from the Brazilian government to research mosquito-born diseases.

Knowing that São Paulo is a city filled with immigrant neighborhoods, their original plan was to analyze four neighborhoods — some associated with immigration and others not — and compare health data and outcomes.

But they soon realized that wouldn't yield the depth of analysis they were after. Instead, they chose to focus intensively on one complex block of one neighborhood — a kind of culturally-rich ground zero, with occupants that range from immigrant sweatshops to a former 19th century public health center that is today a museum of public health.

"We came to the realization that in this one block we could look at the question of migration and health over a long period of time," Lesser said.

"And along with a fascinating migration history — this neighborhood of Italian, Armenian, Jewish and Brazilian immigrants — we also know that the movement of people has always been associated with disease," Kitron said.

"We can go all the way back to the beginning of the 1800s and literally map how this block developed," he added.

Giving life to a research vision

One question that intrigues both professors: What is the continuity and the change in disease over a long period of time?

"Most people have a progressive view of history — things change and get better," Lesser said. "We're asking, 'Did things change and did they get better?'"

The project will also probe the relationship between government notions of how to keep people healthy and the public's ideas of how to maintain good health. "In an immigrant neighborhood, what Brazilians of Korean origin think leads to good health outcomes isn't always what Brazilians of the Northeast think," he said.

Beyond collecting data, Kitron and Lesser are interested in refining research methods that can be applied to other projects, in other places. "That's what really excites us about this," Kitron said. "We are both the professors and the students at the same time."

As for outcomes, "our idea isn't just to write an academic article and book — we want to build something more vibrant and interactive, a virtual way for someone who has never been to Brazil to enter the project," Lesser said.

"That's where the Interdisciplinary Faculty Fellowship really comes in," Kitron added. "We're trying to do something truly trans-disciplinary, to come up with something new in terms of methodology."

"We have a researchable vision," he said. "The IFF is helping to give it life."