It's an image that few will forget: Clad head to toe in a white protective suit, a patient steps gingerly from the back of an ambulance, steadied by a health care worker in the same gear.

As Kent Brantly slowly makes his way into Emory University Hospital on Aug. 2, 2014, amidst an avalanche of media coverage, he becomes the first person with Ebola virus disease treated in the United States — propelling Emory into the international spotlight and beginning a journey of clinical care, research and education that continues to this day.

Brantly, a doctor himself, contracted Ebola while serving as a medical missionary in Liberia, which along with Guinea and Sierra Leone was the epicenter of the worst Ebola outbreak in history. As worldwide concern grew, Emory's Dr. Bruce Ribner received a phone call for which he and a team of dedicated health care professionals had spent a dozen years preparing.

Ribner serves as medical director of Emory University Hospital's Serious Communicable Diseases Unit, a highly specialized unit built in 2002 in collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to care for CDC scientists and others who have traveled abroad and become exposed to infectious diseases. Prior to last summer, only two patients suspected of having highly contagious diseases had been treated there, and both turned out to be negative.

But only 72 hours after the U.S. State Department called to ask if Emory would take Brantly, he was transferred from a specially equipped airplane that flew him out of Liberia and into that ambulance and the care of specially trained doctors, nurses and other health workers, some of whom gave up vacations to be part of his team. While EUH staff cared for Brantly and fellow missionary Nancy Writebol, who worked at the same hospital in Liberia and arrived three days later, Emory also worked to quell public anxiety.

"We can either let our actions be guided by misunderstandings, fear and self-interest, or we can lead by knowledge, science and compassion," Susan Grant, chief nurse for Emory Healthcare, wrote in an op-ed for the Washington Post soon after Brantley's arrival. "We can fear, or we can care."

That philosophy guided Emory University Hospital and the entire university community through the care of four patients with Ebola virus disease:

Brantly, who was discharged after an emotional press conference on Aug. 21, 2014.

Writebol, who was admitted Aug. 5 and quietly discharged, according to her wishes, on Aug. 19.

Ian Crozier, who was admitted on Sept. 9 and discharged Oct. 19. A doctor who volunteered with the World Health Organization at the Ebola Treatment Unit in Kenema, Sierra Leone, Crozier was the most critically ill of Emory's Ebola patients, requiring both kidney dialysis and a ventilator.

Amber Vinson, who was transferred to Emory University Hospital on Oct. 15 and discharged Oct. 28. A nurse, Vinson was treated at Emory by request of the CDC and Texas Health Resources after becoming infected while caring for a patient with Ebola virus disease at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas.

Now, on the first anniversary of Ebola treatment in the United States, public fears about the virus have waned, but Emory's commitment to caring remains strong.

First a leader in clinical care of Ebola patients, Emory is now an international leader in researching the disease and helping both developing nations and the United States prepare for future public health emergencies.

When President Obama visited the CDC in September to announce a significant expansion in the United States' commitment to fighting Ebola, he met privately with members of the Emory Healthcare team, then publicly praised Emory's "extraordinary efforts" during a nationally televised press conference.

Emory experts have shared their protocols and knowledge gained from treating these patients through a variety of journal publications, training conferences and an extensive public website for health care organizations regarding best practices for safe and effective screening, diagnosis and treatment of Ebola virus disease. To date, more than 22,000 people have registered at the site.

Earlier this month, Emory was tapped to lead the new National Ebola Training and Education Center (NETEC), in collaboration with the University of Nebraska Medical Center and the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation (Bellevue Hospital).

It's a year that Ribner, who will serve as principal investigator for the NETEC, says he couldn't possibly have predicted.

"We thought what we were doing was important, but we never expected to be thrust on the international stage the way we have been," he notes. "I think Emory did a phenomenal job."

Story Extras

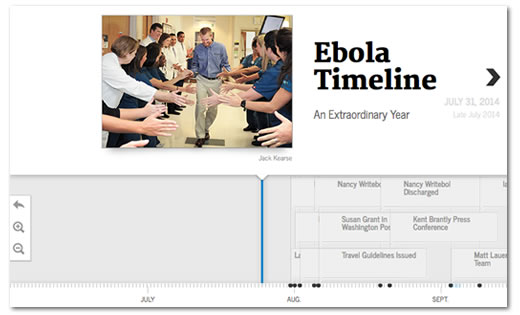

Emory and Ebola: A Timeline

With text, photos and videos, this interactive timeline chronicles key events of the last year, from the days just prior to the arrival of the first Ebola patient at Emory University Hospital, up to the present day.

Video Playlist

From Emory's YouTube channel: a year's worth of Ebola videos.

Top Videos:

- Ebola at Emory: An Extraordinary Year

- Ebola in the Eye: Ian Crozier's Story

- Emory University Hospital Isolation Unit

- Ebola Vaccine at Emory's Hope Clinic

- Ebola Plasma

Book Excerpt

Dr. Kent Brantly, the first person with Ebola virus disease in the United States, arrived at Emory University Hospital on Aug. 2, 2014. As the anniversary of his successful treatment at Emory approaches, Brantly has just published a memoir with his wife, Amber, titled "Called for Life: How Loving Our Neighbor Led Us into the Heart of the Ebola Epidemic."

Excerpt: "Out of Isolation"