Yerkes National Primate Research Center researchers are the first to show that an irradiation plus transplantation combination approach in nonhuman primates can be used to treat or even possibly cure HIV/AIDS, and this new model is providing some answers about the "Berlin patient," the only human thought cured of AIDS. The study is published in the September 25 issue of PLOS Pathogens.

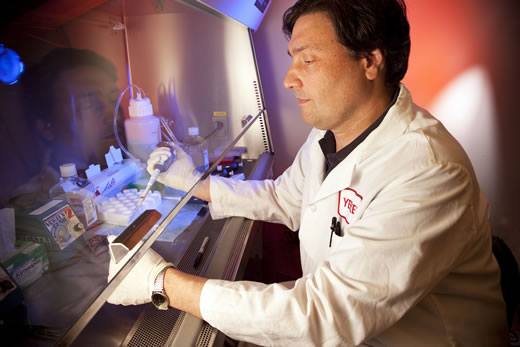

Guido Silvestri, MD, division chief of Microbiology and Immunology at the Yerkes Research Center at Emory, and several of his research colleagues performed the first hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in three rhesus macaques infected with a simian human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV). Silvestri's colleagues on this study include Maud Mavigner, PhD, Yerkes and Emory Vaccine Center, Ann Chahroudi, MD, PhD, Emory University School of Medicine (EUSOM) Department of Pediatrics, and Leslie Kean, MD, PhD, and Benjamin Watkins, MD, EUSOM Department of Surgery.

The team of researchers harvested hematopoietic stem cells from three macaques prior to SHIV infection of all six animals in the study, treated the animals with anti-retroviral therapy (ART) to reduce viral load and mimic the situation in human HIV-infected patients who are treated with ART, and then exposed the three monkeys from which they had collected hematopoietic stem cells to a high dose of radiation. According to Silvestri, "This treatment eliminated most of the existing blood and immune cells, including up to 99% of the animals' CD4-T cells, which is the main target of HIV infection."

Following the irradiation, the researchers transplanted each monkey's own virus-free hematopoietic stem cells. The stem cells regenerated blood and immune cells in all three monkeys within six weeks, at which time the scientists stopped ART in all of the monkeys.

"As we expected, the virus rebounded rapidly in the control animals," says Silvestri. "Of the three transplanted animals, two also showed a rapid rebound, while the third animal had no rebound for two weeks. Unfortunately, we had to euthanize this monkey because of kidney failure, so we don't know how long this control would have lasted." Post-mortem analysis of the monkey that experienced no virus rebound after ART interruption showed low levels of viral DNA in a number of tissues.

Silvestri says, "These results support our hypothesis that a massive depletion of hematolymphoid cells by total body irradiation can cause a significant decrease in the viral reservoir in the body. At least in one monkey, we were very close to eliminating all reservoirs, so we think this approach is promising. We'll use what we've learned in this test-of-concept study to refine our research model toward our goal of curing HIV infection in all humans."

An added benefit of the researchers' work is providing insight into the cure of the Berlin patient, who was HIV-infected before irradiation for leukemia and then a bone marrow transplant. The transplant was from a donor who had a mutation that abolishes the function of the CCR5 gene, which codes for a protein that facilitates HIV entry into human cells. The mutation in homozygous carriers who, like the donor, have two defective copies protects against HIV infection. The researchers say using the CCR5 mutant donation and/or the presence of graft versus host disease, which results in the elimination of HIV-positive reservoir cells that survive irradiation, played a significant role in curing the Berlin patient.

Yerkes National Primate Research Center

Established in 1930, the Yerkes National Primate Research Center paved the way for what has become the National Institutes of Health-funded National Primate Research Center (NPRC) program. For more than eight decades, the Yerkes Research Center has been dedicated to conducting essential basic science and translational research to advance scientific understanding and to improve human health and well-being. Today, the Yerkes Research Center is one of only eight NPRCs. The center provides leadership, training and resources to foster scientific creativity, collaboration and discoveries, and research at the center is grounded in scientific integrity, expert knowledge, respect for colleagues, an open exchange of ideas and compassionate, quality animal care.

Within the fields of microbiology and immunology, neurologic diseases, neuropharmacology, behavioral, cognitive and developmental neuroscience, and psychiatric disorders, the center's research programs are seeking ways to: develop vaccines for infectious and noninfectious diseases; understand the basic neurobiology and genetics of social behavior and develop new treatment strategies for improving social functioning in social disorders such as autism; interpret brain activity through imaging; increase understanding of progressive illnesses such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases; unlock the secrets of memory; treat drug addiction; determine how the interaction between genetics and society shape who we are; and advance knowledge about the evolutionary links between biology and behavior.