When Oxford College Professor Frank Maddox goes to China on sabbatical this fall, studying business culture and central banking to enhance what he brings to his economics classes will be only part of the picture.

Also high on his agenda: special training in Chinese language studies.

For Maddox, an associate professor of economics, the desire to master the basics of modern standard Chinese — a spoken form of Chinese based upon the Beijing dialect of Mandarin — has grown along with the increasing number of Chinese students arriving in his classrooms.

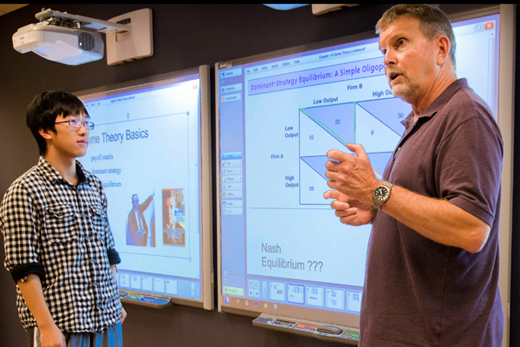

"This summer, I'm teaching an intermediate microeconomics class [for Emory College] and over half of my students are Chinese," he says. "It's the new norm."

In fact, Maddox can trace his yearning to better communicate with Chinese students to Fall 2010, when he discovered that over half of the students in his Economics 101 class were from China — part of a surge in international students to enroll in Emory and Oxford Colleges over the past four years that has left his classroom "forever changed."

For years, Maddox had enjoyed the opportunity to get to know his students, casually visiting with them before or after classes and during office hours, creating relationships that were often sustained beyond their college years and typify the Oxford experience.

But with his Chinese students, Maddox discovered, to his embarrassment, that he didn't even know how to pronounce their names.

"Much of the joy I had always experienced getting to know students was challenged," he acknowledges. "That was a big change for me. And I realized that I was the one who needed to adjust."

A boom in international students

As the percentage of international students seeking out Emory has grown in recent years — bringing both diversity and new perspectives into the classroom — more faculty have come to the same realization.

The University's international student body has more than doubled over the last decade to 2,400 students; international students now make up 16 percent of the overall student population, representing an increasingly diverse list of more than 100 countries. For the 2013-2014 academic year, more than 1,000 Emory students came from China — 41 percent of the University's international student body and 7 percent of the student body as a whole, according to the Office of International Affairs.

While the University offers an array of programs to help international students adjust to campus life in the U.S. — from the Academics and Culture at Emory (ACE) program to international study groups, receptions and roundtables — more faculty and staff are now seeking ways to ease the communication gap.

For Maddox, those efforts began in earnest last year, when one of his international students helped him learn a bit of Chinese to use while teaching summer school.

"At first, I thought there was no sense that could be made of the language," admits Maddox, who had studied German during his own college days.

But the language was captivating, compelling him to seek out more instruction through a Rosetta Stone Language Learning series. "By the end of summer I had completed all five sessions," he says. "And I find that I actually love the language. It's very nuanced and respectful."

A tonal language — the same word can mean something entirely different based upon spoken inflection — standard Chinese is often said to be among the most difficult languages for English speakers to master, Maddox acknowledges.

"You have to be careful or you can call someone's mother a horse," he jokes.

Yet, Maddox is very much enjoying the challenge: "At first you think, 'Oh, I could never do that' and then you're doing it," he says. "Every day is like an Easter egg hunt — I keep discovering new words."

Participation in free classes grows

It was a collision of language and culture that prompted Italian lecturer Simona Muratore to seek out Chinese language instruction.

Like Maddox, she observed a growing number of Chinese students enrolling in her Italian language classes at Emory who were "struggling with learning the language — and I was kind of frustrated because I couldn't communicate with them in either Italian or English," recalls Muratore, who teaches in the Department of French and Italian at Emory.

When Muratore learned that free Chinese language classes were being offered to Emory faculty and staff last fall through the Confucius Institute (CI) in Atlanta at Emory, she decided to participate "to see if it could help me better understand where they were struggling."

"Coming to the United States from Italy myself, I know that it felt good to hear people speaking even just a few sentences of your own language," she adds. "I only attended (the Chinese class) one semester, but it gave me some basics, a way to connect."

Established in 2008, the CI is an educational partnership between Emory and Nanjing University in China and was the first program of its kind in Georgia, designed to raise awareness and understanding of Chinese language, culture and society, says CI Director Rong Cai, associate professor of Chinese in the Department of Russian and East Asian Languages and Cultures.

As Cai recalls, "we started to offer the (Chinese language) classes to Emory faculty and staff in 2012 and expanded it to include graduate students in 2013." Last fall, when the CI issued a call for applications "we got more than 40 faculty, staff and students, so opened two sections," she adds.

"We have an increasing number of Chinese students coming to Emory," Cai says. "Sometimes communication is hampered by language and cultural differences. Our classes offer an opportunity to learn Chinese language to facilitate communication and to help faculty do research."

"As China has become more prominent on the world stage, we hope that more faculty will be interested in knowing China and doing comparative studies, so this is an opportunity to help facilitate those research efforts," she continues.

With a focus on listening and speaking Chinese, the non-accredited classes are designed to be fun and pressure-free, Cai explains.

"We're offering a window into the Chinese language," she says. "The emphasis is on communicative ability or skills as opposed to an accredited class. There is no exam at the end of the semester, so people tend to get out of it what they want."

Free Chinese classes will again be offered through the CI this fall; those interested in applying should check the CI webpage for updated information, Cai says.

Language pays dividends in classroom

In September, Maddox will leave for Beijing, where with the help of a faculty development grant, he'll attend a seven-week language immersion program coordinated through Next Step China that will allow him to work directly with a tutor four hours a day.

Although he visited China before in 2012 through Emory's Halle Institute, Maddox looks forward to unraveling aspects of language and culture that he believes will pay dividends in the classroom.

"So much culture is wrapped up in words," he says. "Occasionally in class, I'll drop a phrase or two in Chinese, which students seem to appreciate. But I want to be to the point that I can casually chat with them, engage them."

Fortunately for Maddox — who grew up in rural Madison, Georgia — the soft, Southern tones in his own voice haven't posed a barrier in speaking Chinese so far.

"When speaking Chinese, I don't think there's any room for drawling," he chuckles. "I've actually been told that I have, of all things, a Beijing accent, which is more formal and not as colloquial as I would like it to be. So I'll be working on that."