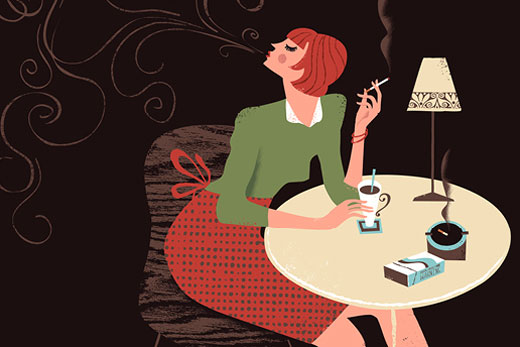

Every Sunday night, I love to watch Mad Men, a drama set in a high-flying, high-pressure New York advertising agency in the 1960s. There are engrossing story lines, snazzy mid-century set designs, and smoke—lots of smoke. The characters smoke at home, in the office, in restaurants. They smoke so much that I wonder how they find their desks through the haze.

Today that situation is upended. One would be hard pressed to find an office where ashtrays are commonplace and smoking is allowed. Knowledge about the devastating health effects of firsthand and secondhand smoke has led many to steer clear of cigarettes or to kick the habit.

The first U.S. Surgeon General's report to address smoking and its health hazards was in 1964.

The government then jumped in further and required warning labels on tobacco products, raised taxes for cigarettes, and mandated that they be kept behind store counters. It banned television advertising of cigarettes in 1971, followed by billboard ads in 1999. In turn, insurance companies began charging higher medical premiums for smokers and pushed cessation programs. In 1980, the Nonsmokers Rights Movement began to enact smoke-free workplace laws that now prevail in restaurants, bars, and even some casinos. Workplaces—including Emory—have banned smoking on company property, even outside.

All of these moves, Emory researchers say, have led to a decline in smoking. Although it is no longer cool—the Marlboro Man rode off into the sunset years ago—some 19.8 percent of Americans still smoke, according to the CDC. For this group, no public health or medical intervention has worked—not the cringe-worthy television commercials showing people with advanced-stage lung cancer, not strong health warnings on cigarette packs, not the availability of nicotine patches and gum. Why?