Food was inseparable from religious life at the Black Baptist church Derek Hicks attended as a child in Los Angeles.

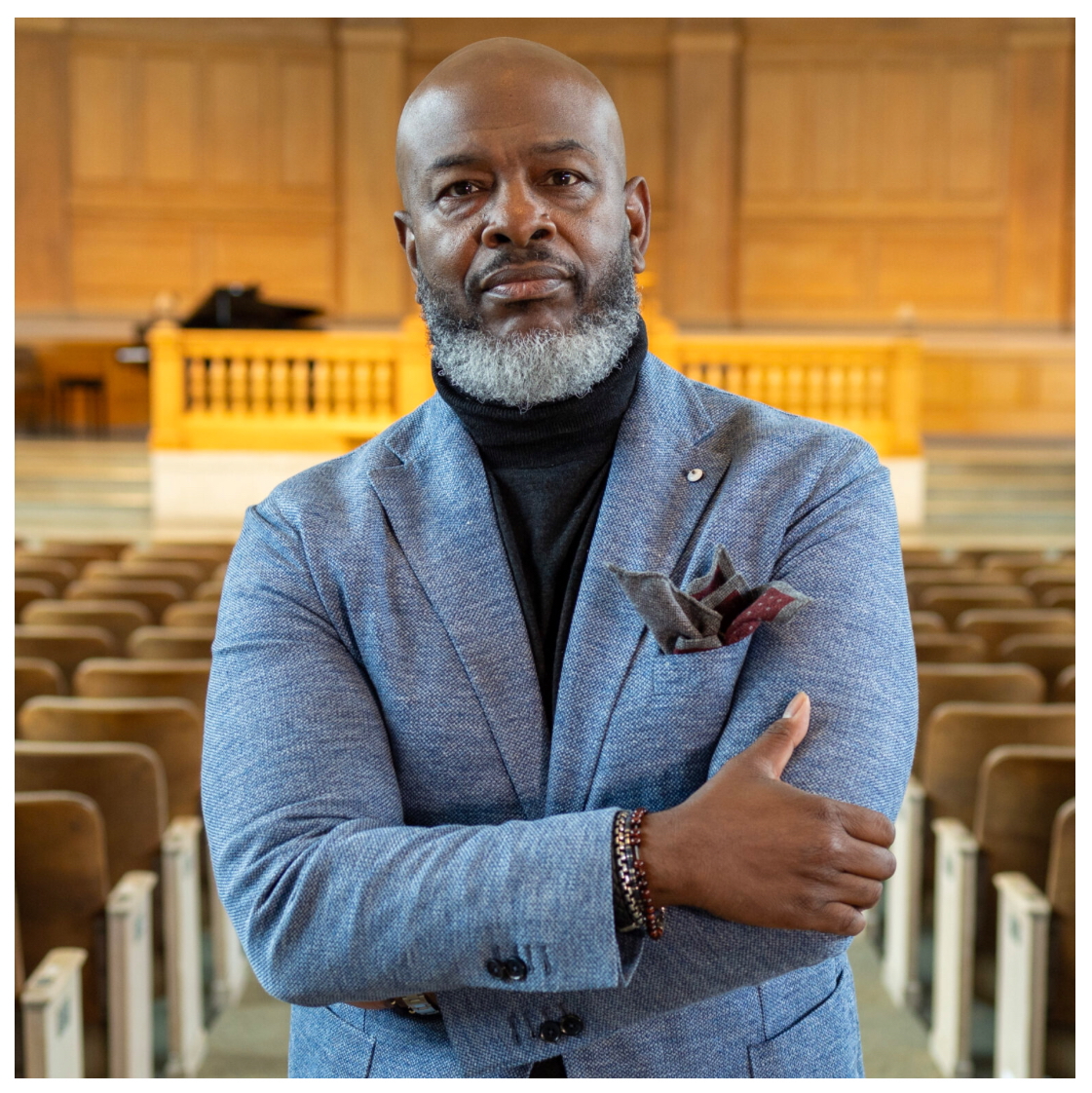

Each Sunday, “there was somebody’s house where we would go to eat,” says Hicks, a visiting scholar in Candler School of Theology’s Sankofa Scholar Program.

“Well before she would get to church on Sunday mornings, one of the church mothers already prepping and cooking. By 3 p.m. — and this is after three services — she was serving food. And we would go!”

This kind of storytelling forms the backbone of “Culinary Culture in Black Religious Experiences,” a course Hicks developed at Wake Forest University School of Divinity where he is associate professor of religion and culture.

He recently taught the course at Emory as an intensive, week-long January term, or J-term, class. Housed in the Black Church Studies program at Candler School of Theology, the class was cross listed in history and sociology.

"Religion is about meaning making,” says Derek Hicks, a Candler School of Theology visiting scholar. “It’s also a way of expressing oneself. I started realizing food is doing the same thing.”

“These are celebrated and emerging Black scholars who complement the robust faculty we have,” says Nichole Phillips, associate professor in the practice of religion and society and director of Black Church Studies at Candler. “Dr. Hicks really is at the forefront when it comes to the intersection of African American religious experience and food, so we were thrilled to bring him to campus.”

Evidently, Emory students were hungry for what he was serving up. The class’s 27 seats filled quickly.

“Well, we call it ‘soul food’ for a reason,” Phillips says. “Food, in many respects, is comparable to spirituality in that it satiates the soul, the spirit and the body, in many different ways. And I think the students want a piece of that!” she adds, laughing.

Past Sankofa Scholars include Katie Cannon, a Black Christian social ethicist and liberation theology expert who helped establish womanism, a form of activism rooted in Black women’s religious and lived experiences; Stacey Floyd Thomas, a Christian ethicist who earned her master’s degree in theological studies from Candler; and Obery Hendricks, a New Testament scholar and public theologian.

In the following Q&A, Hicks discusses the intersection of Black American culinary practices and religious life, positing that you can’t have one without the other. He also touches on questions of authenticity and place-based traditions spanning generations.

What are some examples of how food accompanies Black American religious practices?

There’s nothing like the experience of a Black funeral as it relates to this. Once, I took a friend who had not attended a Black church to a funeral in a faith tradition that was Baptist merged with Pentecostal.

And as we’re leaving to go to the cemetery, we are handed containers of food. It’s a piece of chicken, some potato salad, maybe a slice of bread and green beans. So, we take those with us to the gravesite, where we eat them.

The body is committed. Then I say, “Well, now we have the repast,” which is a meal.

And my friend was like, “Wait, we just had a meal.”

But that container of food was just to hold us over. “Repast” is full plates and a full celebration to commit our souls to the communal experience of the homegoing.

And we do that around food. Examples abound. I recall Friday-night fish fries that would start off as spiritual experiences with the sharing of Bible passages that gave way, later in the evening, to dancing to [the music of] B.B. King and Bobby Blue Bland.

That also becomes a part of the spiritual experience of binding the community.

What parallels do you see between the ways people think about Black culinary traditions and religion?

Students enjoy a light moment in “Culinary Culture in Black Religious Experiences,” the J-term class taught by Hicks.

Photo by Kay Hinton

The way I talk about religion, asking, “What is authentic?” is the same way Black folk talk about food. We have conversations about authenticity in what we call, dare I say, “soul food.” What is authentic about one’s sweet potato pie or one’s gumbo? Or, like my aunt, who used to bust through the door on Thanksgiving, yelling out that nobody had better make any red velvet cake, because hers was the authentic red velvet cake.

There’s meaning associated with how she prepares it and with the ingredients. And those were data checkpoints to see if authenticity was actually there.

Another example is gumbo and debates about the best hot sauce. You know, one or two hot sauces are going into my gumbo, and that’s Louisiana Hot Sauce or Crystal. That’s it. There is no debate. But in this region of North Carolina where I currently live, it’s all about Texas Pete. All of these particulars play a role in this one dish that is, in itself, beautiful, complex and soul-feeding.

So, I start seeing that, wow, culinary culture as a cultural production is giving some of the same vibes that I’m getting from religion as a cultural production in African American life. And if I overlay those things, what would I get? That’s what brought me here.

What roles have religious activity and cooking played in helping people recreate community in new places?

You think of the Great Migration, [the 20th-century diaspora of Black people from the American South to northern and western cities]. In 1947, my grandmother migrates to Los Angeles. But all that she knew was Colfax, Louisiana. And so, on her front porch in California, she builds community amongst other migrating Southern Black folks.

By the time I'm born, I'm around folks who had migrated from all these places in Louisiana and Mississippi. So, what they talked about, how they worshiped, how they cooked, the type of fish they would have at fish fries — with all of this, they were establishing a “South” in the city.

For example, at my grandparents’ church, they would not seat a senior pastor unless they had plucked him from the South.

They were making decisions that allowed them to see their humanity as full and ever present in this new land of Los Angeles.

What do you enjoy about teaching this class, especially here at Emory?

When I first taught this course, there was less scholarship out there [on this topic]. And now, not only can I assign new scholarship, plus my own work, I can also show several films. I can expose them to farmers and folks who are in the community doing this work.

Each student creates an autobiography of their food and faith journey. They choose just one element of their experience where they can recall the culinary and the spiritual converging in that moment — because the power of story is important, and necessary, to tell this history.

And I’m excited that there are so many students who are interested in this class! I’m pleased that I get to do this with a group of people coming from different vantage points, whose site of investigation is, for all intents and purposes, Atlanta, Georgia.