As October shadows lengthen and Halloween approaches, Emory University’s Ideas Festival offered a fittingly eerie experiment: a live dissection of the horror genre. Psychologist Kenneth Carter and cultural scholar Clint Fluker explored what seeking out scary movies and books reveals about our minds and our culture in a session aptly titled “The Science of Horror.”

Carter studies sensation-seeking behavior — why some people chase risk while others avoid it.

“I’m a chill seeker, not a thrill seeker,” he said, joking that he can’t even make it through two minutes of the body horror movie “Saw.”

His research as Charles Howard Candler Professor of Psychology at Emory shows that people who enjoy horror films tend to have lower stress responses and higher dopamine levels in intense situations. “Some people watch ‘Saw’ and feel fine,” he said. “I can’t do it.”

But Carter emphasized that fear isn’t only about adrenaline.

“People often assume horror is about seeking fear,” he said. “For many viewers, it’s about seeking release.” Just as someone might watch a sad movie “because they need a good cry,” he explained, others turn to horror “because they need a good scare.”

Experiencing fear in a controlled setting can help people manage anxiety in the real world — an emotional reset that allows tension to break safely.

Meanwhile Fluker, senior director of culture, community and partner Engagement for Emory Libraries and the Michael C. Carlos Museum, approaches horror as both a cultural mirror and a historical document. His own fascination with the genre began at Morehouse College, where he watched “King Kong” (1933) in a film class.

“I was struck by the very clear and obvious racial overtones,” he recalled. That moment, he said, sparked his long-term study of how monsters reflect social fears.

“Horror’s goal,” Fluker said, “is to exploit your personal and social anxieties and blow them up.”

Early monster movies, he noted, often defined “difference” itself as frightening — the creature as a stand-in for the outsider. For example, the zombies depicted in the 1930s, which drew from distorted voodoo myths and fears of the “exotic,” were instruments of control; by 1968, “Night of the Living Dead” had inverted that idea, casting a Black protagonist at a time of racial unrest and making the undead a mirror for white middle-class panic and social decay, he said.

“The monster might win,” Fluker added, “but the real story is about what we’re afraid of.”

Carter brought a scientific lens to that same phenomenon. He explained that fear triggers the body’s stress systems — heart rate, adrenaline and cortisol — but in a theater or at home, viewers know they’re safe. That knowledge lets them toggle between fear and relief, a process that can leave them feeling calmer afterward.

“It’s a way to experience fear without real-world consequences,” Carter said.

A scholar of Afrofuturism and speculative art, Fluker framed horror as both historical and futuristic — a genre where old mythologies, present fears and sci-fi innovations can converge. He connected it to contemporary anxieties around technology and artificial intelligence, noting that “our monsters have evolved with us.”

Today the bogeyman often wears a different mask. Creatures that once embodied racial or colonial fears now might take the form of a sentient machine or a pandemic virus.

Fluker pointed to the recent TV show “Alien: Earth,” where the jump scares still come from monstrous xenomorphs but the deeper dread pools around AI, cyborgs and human minds uploaded into synthetic bodies. The real anxiety in this case, he suggested, is whether our own tools will replace us.

“[These horrors] tell us what we’re worried about,” Fluker said. “And if we pay attention, they might also show us how to overcome them.”

Carter sees a similar dynamic at play in why horror audiences keep coming back. For many, the genre serves as a kind of emotional conditioning.

“What horror lets you do is practice being afraid in a place where you know you’re safe,” he said. “It’s almost like a kind of rehearsal — you feel the same physiological response, but you also get to calm yourself down.” That balance between anticipation and control — the roller coaster that always ends safely — may be what makes horror so enduring, he said.

For Fluker, the endurance of horror is also about community. Watching a film together allows people to externalize fear, laugh afterward and talk about it — a ritual as old as ghost stories around a campfire. Horror, he said, gives people a way to face what frightens them collectively.

While these two scholars approached the topic from different directions — science and culture — they arrived at a shared conclusion: horror movies and books are a safe space for confronting the unsafe. It’s both psychological and social, deeply personal yet widely shared. The monsters change but the impulse stays the same.

Fluker described that impulse as an act of choice. “You get to decide whether to stay and face the monster,” he said.

That control, paradoxically, is what makes fear pleasurable. In a world filled with uncontrollable threats, horror offers a moment of agency — to open the door, to look anyway, to survive and even laugh afterward.

The psychology of thrills and chills

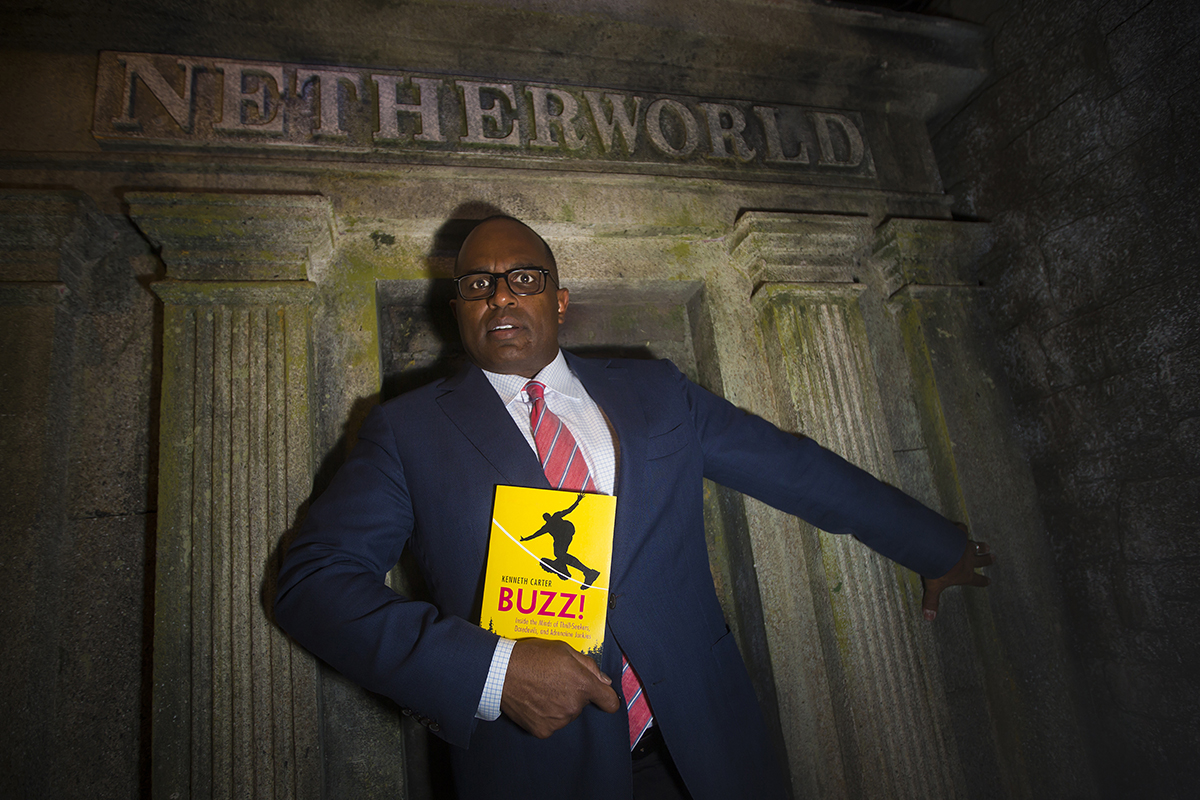

Psychologist Kenneth Carter is not a fan of Halloween haunted houses. But he has conducted research — and written a book — about people who thrive on activities like entering dark passageways, sensing that something unknown and terrifying awaits around the next corner.