You could say it started with the llamas.

In 2017, the Michael C. Carlos Museum hosted an event with activities for families related to an exhibit about indigenous American textiles.

“An Emory undergraduate student was walking by, and stopped,” says Katie Ericson-Baskin, the museum’s director of education.

The student looked at the live llamas, Peruvian food trucks and feather fan craft, and asked, “I know this is for kids, but can I participate, too?”

Of course, said museum staff.

The student petted the animals, worked on the craft project alongside seven- and eight-year-olds and left refreshed.

“And we thought: ‘Okay. We have to have opportunities like this for our university students,” says Ericson-Baskin. “You know, so they’re not feeling like they have to crash the families’ day.”

Now the Carlos hosts drop-in art workshops for students the last Friday of every month.

The museum’s commitment to nurturing the connection between well-being and the arts keeps growing.

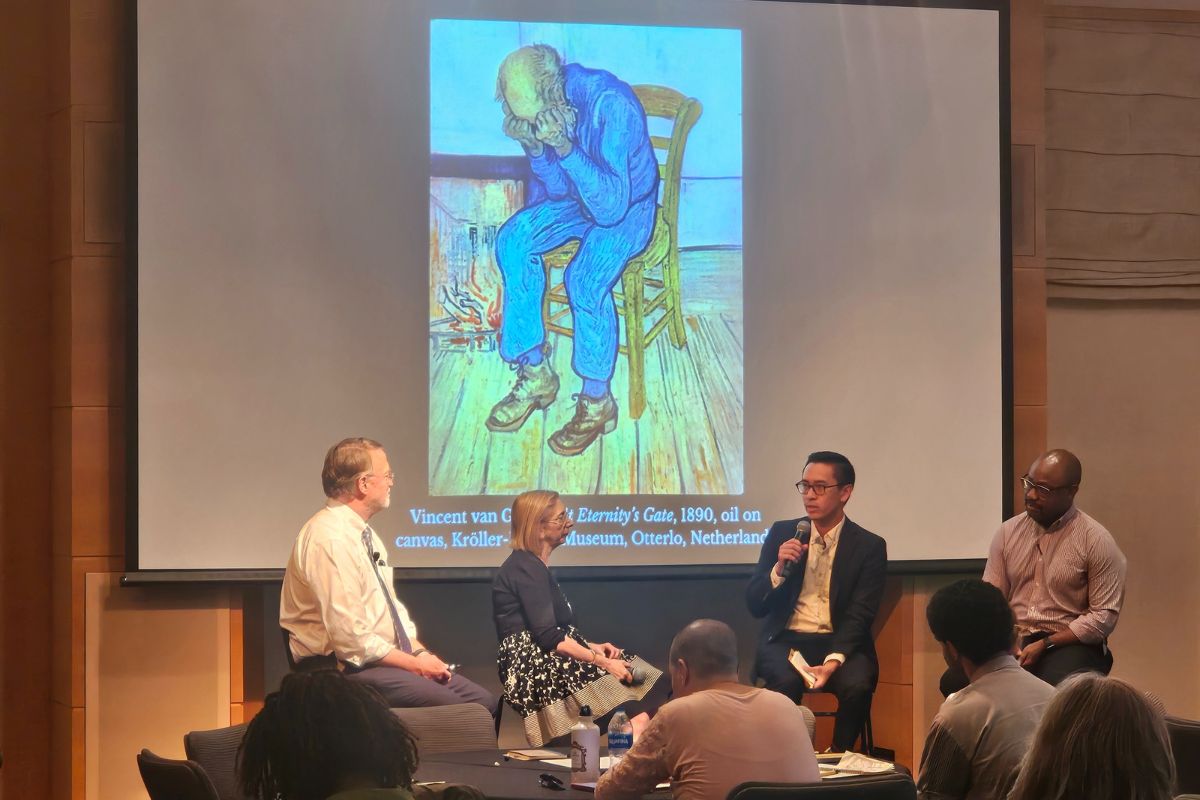

In April, the Carlos Museum hosted its first Arts and Wellbeing Summit, an event devoted this year to exploring how art can help process grief.

Visitors enjoyed music from Atlanta Symphony Orchestra musicians in the museum’s galleries.

“This summit is important to us,” says Henry Kim, associate vice provost and director of the Carlos, “because it reinforces our interest in understanding the science behind the role the arts have in people’s well-being. By bringing this community together, we hope not only to raise attention to this important work, but to inspire future research work.”

Health care practitioners, researchers, artists and advocates convened during the summit for panel discussions. Participating organizations included Emory School of Medicine, The Carter Center, the Atlanta Trauma Alliance and the Grief House — a nonprofit offering bereavement support.

The summit also featured hands-on workshops for visitors, including drawing, textile jewelry-making, dance, sculpting in cardboard and letter writing, along with free performances by musicians from Atlanta Symphony Orchestra.

The summit was co-sponsored by the Carlos Museum and Performance Hypothesis, a firm dedicated to improving health through creative programming, with support from Barbara and Larry Schulz.

Artistic prescriptions for health

The scientific research linking the creation and enjoyment of art with well-being goes back decades, says Bill Eley, executive associate dean for medical education and student affairs at Emory School of Medicine.

“There’s a huge amount of data about neuroplasticity and how what practices we choose to engage in affect the way our brain is wired,” says Eley. “Things like gratitude and positivity can literally rewire our brains and give us a better life. And art? Well, art is beauty. Whether it’s a play, a movie, a painting or the written word, it moves us.”

The health care world has taken note of this connection. Ericson-Baskin explains that the Carlos works with doctors who write evidence-based “arts prescriptions,” such as visits to the museum for people struggling with depression and anxiety.

“There’s this great movement happening,” she says. “And we’re really wanting, not just to join in that momentum, but to be a leader in some of these conversations, especially as an institution that really cares about its role in the wider community.”

The museum’s work in recent years underscores that leadership.

Last October, the museum hosted a day of Healing Arts Atlanta, a five-day symposium convening organizations from across the city dedicated to the intersection among the arts, health equity and wellness.

In 2023 and 2024, the Carlos partnered with the addiction-support nonprofit R2ise 2 Recovery to host the “Comfort of Recovery” quilt, handcrafted by people helped by the organization. The Carlos shepherded the display of the quilt throughout the university and hospital campus.

Then there are the museum’s hands-on partnerships. The Carlos works with the Emory Healthcare Veterans Program to host art-making workshops for veterans experiencing PTSD.

The museum also partners with Emory School of Medicine to bring medical students to the museum to visit galleries, reflect and take part in drawing workshops.

Last year, the Carlos offered another drawing workshop geared for Emory physicians and medical residents.

“And, you know,” says Ericson-Baskin, laughing, “many of the doctors would draw something and say, ‘This is comically bad,’ but they had fun doing it, right? They arrived, rushing in and tired, but left, happy and joking. We’re creating these opportunities for connection and camaraderie.”

Making meaning of loss

The topic of the inaugural summit came about organically.

“We were initially thinking about [former] U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy’s comments about loneliness being a huge issue for our time,” says Ericson-Baskin.

But when the Carlos staff considered what might trigger that loneliness, they found themselves discussing the COVID-19 pandemic and difficult events taking place around the world today. The throughline, they realized, was grief.

Nadine Kaslow, professor and vice chair of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the School of Medicine, agrees.

During the pandemic, she hosted grief support groups for staff at hospitals across the city. But she notes that while the anniversary of the Sept. 11 attacks is acknowledged by a moment of silence and there are national memorials to recognize the impact of major wars on people, “for COVID, we never were able to engage in collective grieving and healing.”

For this reason, in March, Kaslow helped organize “Five-Year COVID Commemoration: A Time to Remember, Reflect and Connect,” at Grady Memorial Hospital for Emory and Morehouse Schools of Medicine. The Emory-Grady Choir sang.

“A lot of people were crying,” she says.

She believes that engagement in the arts — such as that choral performance — can play an instrumental role in both the mourning and healing processes.

For one, it can allow people to express difficult emotions. Kaslow, who’s performed ballet since age three, has danced at several friends’ funerals. “And that was a way to honor them where I didn’t need words,” she says.

Kaslow also notes that grieving is a process of making sense of one’s loss, and art can help with that, too. “Creative work and engaging in the arts can truly help people find that sense of understanding and ultimately, meaning, which I think is incredibly valuable.”

Making art can also serve as a welcome distraction.

“When I’m dancing or teaching dance,” says Kaslow, “I’m not thinking about stresses or challenges.”

Finally, she says, art helps people to regain a sense of connection with those they’ve lost. “Maybe you draw a picture that reminds you of them,” she says, “or you do some musical production, and the process also potentially redefines your relationship with that person.”

Eley, whose work as an oncologist brings him face-to-face with profound human struggles, says that he has found some of his most moving moments of solace in great art.

“I was at the Prado Museum,” he says, “and there was a painting of Mary looking up at her son dying on the cross. Her expression of grief was so real. The artist had just captured it. We can all see ourselves in the feelings and the suffering of others.”

A community rich in sciences and the arts

Often, the campus serves as that place of distraction and respite for Emory Healthcare workers and medical students, says Eley.

“If you go to the Quad some days, you’ll see nurses from Emory Hospital walking around, just being in nature, or visiting the Carlos to soak in some art,” he says. “It is a great gift for a medical school to be on this university campus.”

As a place of medical, scientific and humanistic inquiry, Emory is the ideal place to host this summit and other events like it, he says.

Ericson-Baskin agrees. “People across the schools are excited to collaborate,” she says. “And we live in such a rich community in Atlanta with so many people who are working on tying the arts in with health.”

Of course, no one needs to wait for a summit to focus on the healing powers of art. That’s something we can do every day, says Eley.

“And if we do this right,” he adds, “we notice beauty. We notice it in a flower, a song, a poem. We try to get people to seek joy, right? And joy is often represented by these human activities of dance and song and art and theater. And I think it’s all connected.”

Photos by Cameron Baskin, except where noted.