During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Michael Carr had time to reflect on the medical landscape of rural Georgia and began thinking about a problem: Rural communities all over the country, including Georgia, had been losing hospitals for many years due to financial strain.

Prof. Michael Carr

“As soon as you take a rural hospital out of a local community, patients suddenly have to drive two or three counties over to get to the most appropriate facility,” says Carr, associate professor of emergency medicine in Emory School of Medicine. “Imagine during a 911 call, a paramedic or EMT identifies that patient has a critical condition, and then they may drive, sometimes an hour or two, just to get to the closest hospital. For stroke, this can be a matter for life and death.”

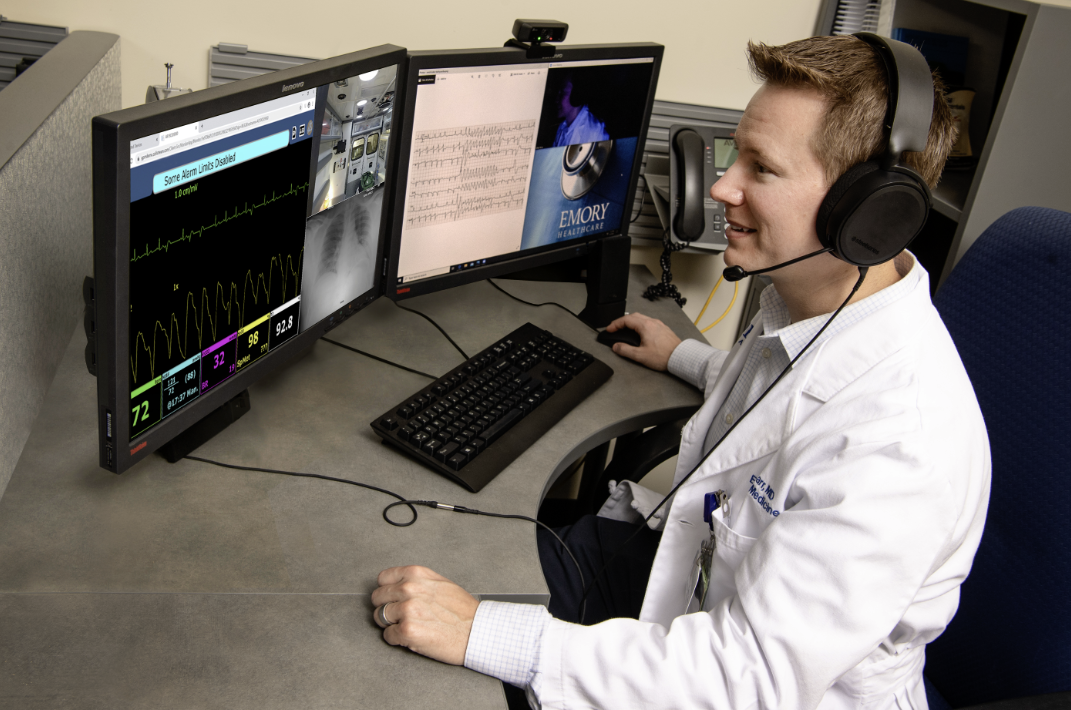

Carr knew clinics had already begun to increase their use of telemedicine as the pandemic accelerated, making it more acceptable for specialists like nephrologists or neurologists to see patients virtually. Carr used a grant from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to create Prehospital and Ambulatory Virtual Emergency Services (PAVES), providing the most advanced telemedicine diagnostic technology to EMT crews.

“The technology is really advanced. For example, the pan-tilt-zoom camera lets us focus in with very high resolution and see the skin, eyes, and pupils,” Carr says. “When paramedics are doing a neuro exam, they can shine the light in the pupils of the patient’s eyes, and we can see them constrict and dilate. All of this can be done in the ambulance.”

However, there were some technological challenges to overcome as well. It took ingenuity, as well as trial and error, to find or create diagnostic technology that could function reliably in a moving ambulance through good weather and bad, on smooth highways and bumpy roads. Carr had to work with technology vendors to find tablets durable enough to survive a drop test of 50 feet so they wouldn’t break if EMS crews accidentally dropped them. Carr’s team also worked with their cellular vendors to find internet connectivity compatible with all cell providers in the state in order to provide connectivity even when the ambulance passed through areas with spotty coverage.

Carr says the original grant showed a system like PAVES can work, but it needs to be expanded beyond the 17 counties of the pilot program. “I have a lot of conversations with legislators about how to fund programs like this,” he says, “To persuade them that the system is especially important in rural areas.”

“Rural residents tend to be older, sicker and poorer,” he says. “The more medical problems you have, the more likely to have critical time-sensitive conditions like heart attacks or strokes. Add in the geographical separation, and that patient is now farther away from a medical facility, primary care, and emergency services. It’s textbook lack of access. That was the opportunity we saw with this grant.”

Because of hospital closures, Carr says 25% of Georgia’s population now lives in so-called healthcare deserts. He believes the digital transformation of emergency medicine can’t fix the whole problem but represents a step in the right direction. “That’s where we are right now,” he says. “This is a call to action.”