The Woodruff Health Sciences Center (WHSC) operates two separate programs that provide free health care and assessments to Georgia migrant farm workers, one out of the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing (SON) and one out of the School of Medicine (SOM), with collaborations across all three WHSC schools and the health care system. Both programs provide free health care to farmworkers and their families in South Georgia.

Farmworkers typically toil from sunup to sundown, six days a week, in blistering heat and pesticide-laden fields picking and packing vegetables, blueberries, pecans, and cotton. Most of these workers have little, if any, access to health care, due to lack of transportation, a language barrier, frequent moves, and inability to take any time off work without risking loss of income.

Emory faculty began working in these areas in 1996. Emory physician assistant (PA) faculty created the Emory Farmworker Project (EFP, previously named the South Georgia Farmworker Health Project) that year, travelling to South Georgia to provide care to farmworkers and learn about rural medicine and the impact of social determinants of health on the health of these communities.

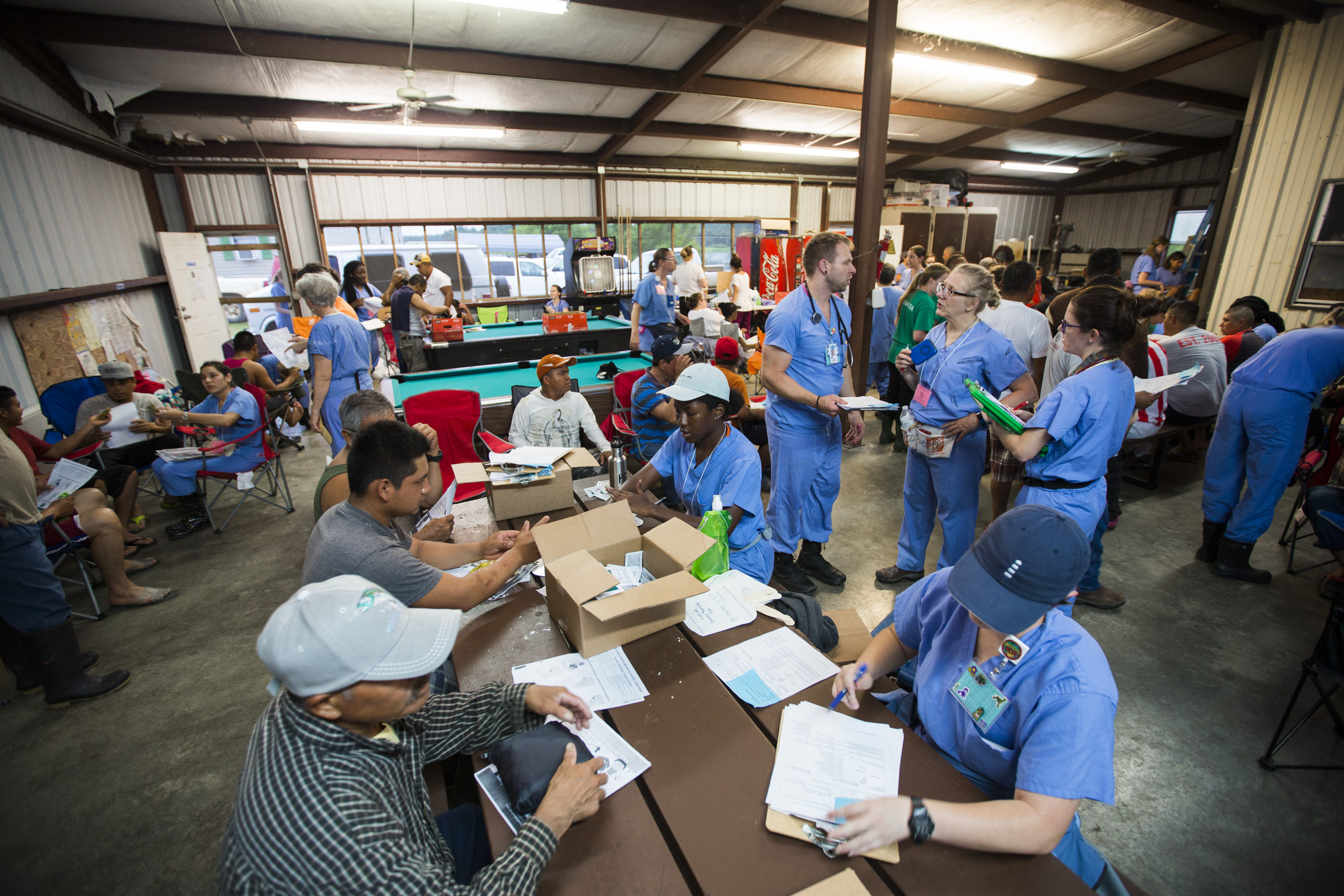

This program began with eight PA students, three PA faculty, and one physician. Today, the EFP is Emory’s largest interprofessional effort involving some 250 students, clinicians, interpreters, and logistics volunteers who come together each summer and fall. The EFP is the hallmark initiative of the PA program and has received local, regional, and national recognition for its innovative, culturally appropriate delivery of care, addressing the health care needs of an often-overlooked population—migrant farmworkers.

Each June, the early-morning and long-evening clinics provide free care for 1,800 or more farmworkers and their family members over 12 days in the fields where they pick crops and in the housing units where the picking teams live. The EFP sees an additional 300 workers during an October weekend clinic.

The interprofessional educational component of the program has grown rapidly over the last five years under the leadership of Jodie Guest, professor in the Rollins School of Public Health (RSPH) and SOM and director of the EFP. “Our mission is two-fold: to provide excellent care without barriers to those who pick our fresh fruits and vegetables and to provide a transformative, team-based educational experience for our students,” says Guest.

The program now includes students from the SOM (PA, MD, MD/PhD and DPT students), RSPH, and the SON. Additionally, faculty and interpreters come from all three WHSC schools and Emory Healthcare. The EFP also partners with the PA Program at Mercer University, family therapy students from Valdosta State University, and medical students and faculty from the University of Georgia, Morehouse University and PCOM. Spanish and Creole interpreters from Atlanta, South Georgia, and Florida volunteer as well.

The EFP brings a basic dispensary of medications, and is able to provide EKGs, ultrasounds, and basic labs in the pop-up clinics. “We see many cases of diabetes though we cannot always confirm if these are new cases are not,“ says Guest. “Because there is minimal to no continuity of care, we are working on novel methods to provide health documentation to the workers as they typically move every six weeks to follow the crops. We are also working on methods to increase health literacy with medications as language is a barrier.”

Over the years, the team has led research finding that 67 percent of the workers are food insecure and has advocated for better policies to ensure access to food and refrigeration. The team has also developed culturally sensitive HIV prevention and eight other educational components that are translated into Spanish and Haitian Creole and available on the patient’s phones. The EFP is currently working with Dell and Verizon to establish access to specialists through telehealth while in fields with limited cell service. This work could also help transform the way they communicate with access to interpreters who are not local.

“The EFP is a time of deep learning for our students,” says Guest. “They see health care issues that are compounded because barriers to care have prevented earlier detection, treatment, or care. They see the real impact of lack of access to care, healthy food, and clean living environments. They grow as providers as they learn to work as a team to provide the best care they can in such austere conditions.”

The SON’s farmworker program had its roots at the Georgia State University School of Nursing, which founded the Farmworker Family Health Program in 1993. The idea was to create an interprofessional, in-country, cultural immersion service-learning experience for various students in health care fields to provide health care services to the farmworkers in Colquitt County and adjacent counties. A win-win situation, where underserved farmworkers gained much-needed access to care while students gained invaluable clinical experience outside of a typical clinical rotation setting. The program moved to the Emory SON in 2001, where it continues to thrive today.

For two weeks every summer, SON faculty, undergraduate and graduate students join dental hygiene, physical therapy, psychology, and pharmacy students from six Georgia universities to deliver health care and health education to farm workers and their children on farms surrounding Moultrie in the heart of Colquitt County. They also will visit farms in three neighboring counties. The trip is timed to coincide with the two-week migrant summer school hosted by the county.

During the day, the program’s team works at the school, providing the complete health assessments. “We service about 400 children during those two weeks,” says Erin Ferranti, an SON cardiometabolic nurse researcher and director of the program. “We do dental, vision, hearing screenings, review their immunizations—basically everything that needs to be done to fill out the forms necessary for the children to attend Georgia public schools.”

Around 6 p.m., the team moves to one of the county’s farms to set up a pop-up clinic outside the barracks where the workers reside. The busses carrying workers from the field generally arrive around 7 p.m., and for the next six hours, team workers provide basic health screenings and general health education. “It’s an intense two weeks,” says Ferranti. “We are in the field until about 1 a.m. every day, and we see about 1,000 farm workers during our time there.”

A fixture at each night camp is the Ellenton Health Clinic mobile unit, where Emory nurse practitioner (NP) faculty and students conduct more thorough physical exams and UGA pharmacy students give out antibiotics (prescribed by NP faculty) for workers who need them. Those with chronic or serious conditions are referred to the actual clinic for follow-up. For some of the workers, the program marks the first time they’ve received basic health and dental care.

“When we pack up and go home, the Ellenton Farmworker Health Clinic outreach workers are the ones who make sure patients have transportation, to the emergency room and back to the farm and for follow-up visits,” Ferranti says. “Ellenton is the heart and soul of that community. We are there to enhance that and provide support during our two weeks there, and we are so proud to be able to serve such an underserved—and deserving—population.”