For Patrick Wurster, MD, the call to global medicine has always been strong. But it wasn’t until he participated in an exchange program in Eldoret, Kenya, that his commitment to international health care truly found its purpose.

“I’ve always had an interest in international work but as a fourth-year medical student I got to do a two-month exchange program in Eldoret, Kenya through AMPATH. It really solidified my intent to work in a similar partnership where the learning is bidirectional, and the initiatives are really led by the local community with support from partners abroad. I want to learn from similar models in ophthalmology so that I can help do some real sustained good in ophthalmology.”

Global ophthalmology is more than just providing eye care; it’s about breaking down the barriers that prevent people from receiving the care they desperately need. Dr. Wurster was drawn to this field because it allows him to give people back their ability to function, and in a way that can echo through entire communities.

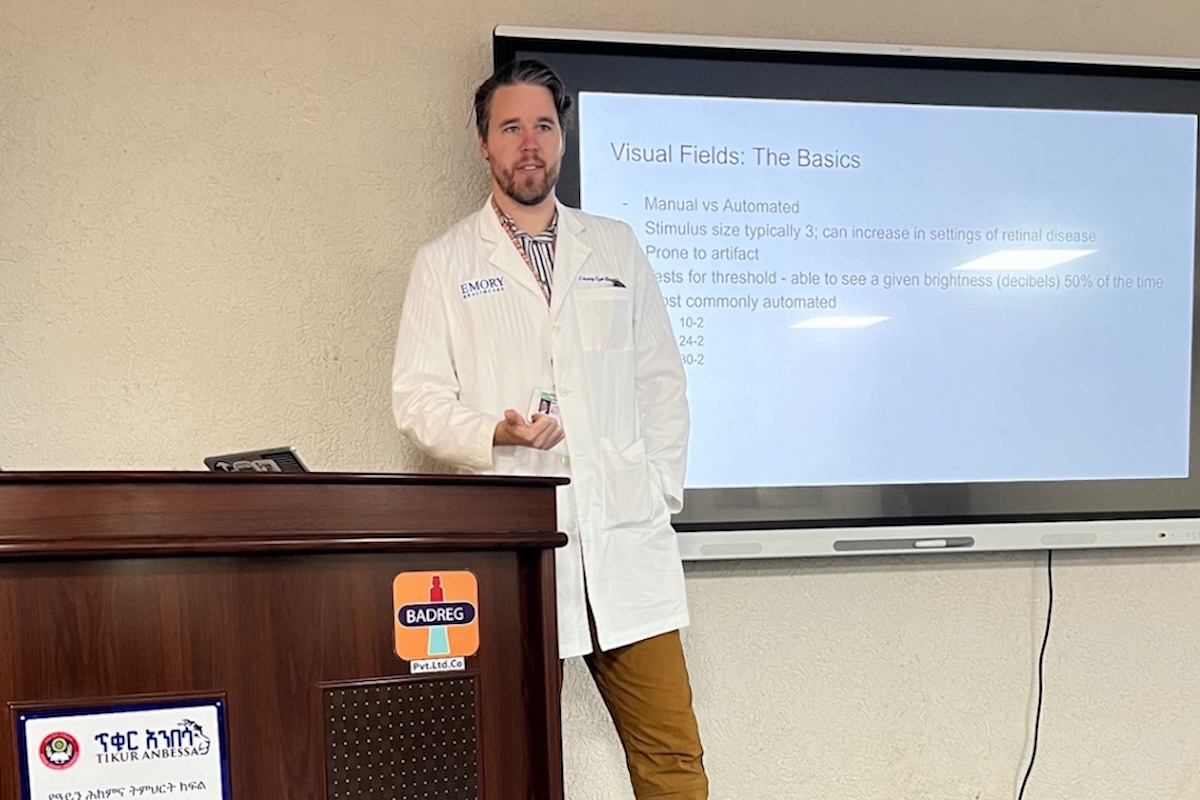

Currently, Patrick is working in Ethiopia, where he partners with the ophthalmology residency program at Menelik II Hospital in Addis Ababa, which has clinics for comprehensive ophthalmology, oculoplastics, retina, glaucoma, pediatrics and anterior segment. The hospital, a government-run facility, is tasked with providing care to some of the country’s most underserved populations. Dr. Wurster’s role is focused on educating residents, but the challenges he encounters there extend far beyond the classroom. His visits are limited to one month at a time, but this short stay is enough to witness the depth of the hospital’s commitment to its mission, even in the face of significant obstacles.

The attending physicians at Menelik II are paid as assistant professors, not surgeons, which means they spend most of their time in private clinics to support themselves financially. Teaching residents happens when they can squeeze it in—often between seeing patients or dealing with their own challenges. Dr. Wurster quickly realized that this struggle to balance patient care and education is a reality for many doctors in resource-poor settings.

His time in Ethiopia has opened his eyes to the multitude of barriers hindering access to care. From the difficulty in retaining skilled physicians to the heartbreaking reality that even basic healthcare is often out of reach for those who need it most, in areas where healthcare is scarce.

“I have learned a lot about the myriad of systemic problems that limit access to care – from difficulty educating and retaining new physicians to barriers experienced by patients attempting to access the care that currently exists. I also learned the critical importance of having antibiotics on-hand for personal use.”

One of the most glaring disparities Dr. Wurster has encountered is the lack of a national insurance system to help patients afford care. In the U.S., an OCT scan—a standard diagnostic tool—is covered by insurance, can be done in minutes, and helps guide treatment decisions. In Ethiopia, however, patients must travel to a private clinic, pay $40 out of pocket for the scan, then return to the hospital with a printout—equivalent to almost an entire month’s wages for many (a median income of $52 monthly). These obstacles add an additional layer of hardship for those already financially struggling.

The differences in medical training are equally striking. In Ethiopia, residency programs feature annual OSCEs and case-based testing. In contrast, U.S. programs rely mainly on the OKAP exam. The experience of being part of the Ethiopian residency program made Dr. Wurster rethink the structure of his own training, especially given the limited supervision in places like Ethiopia compared to the more hands-on approach in the U.S.

Perhaps the most poignant aspect of Patrick's work in Ethiopia is the high rate of residents who plan to leave the country as soon as they complete their training. Nearly every resident Dr. Wurster spoke with expressed a desire to seek better pay and political stability abroad. “The government is trying to increase the number of ophthalmologists, but when they all leave as soon as they’re trained, it becomes a lost investment,” Dr. Wurster noted. The exodus of skilled doctors leaves the country in a difficult position, forcing the cycle of brain drain to continue.

Amid these challenges, one of the most fulfilling aspects of Patrick’s work abroad has been his realization of how deeply he loves teaching. “I learned I love teaching much more than I realized. I would love to continue to work with people in this program longitudinally going forward in some capacity, although the physical distance and associated time change may make this challenging. Additionally, the paucity of available testing was a great reminder of the importance of a good exam.”

Dr. Wurster’s journey in global ophthalmology has opened his eyes to both the profound challenges and the immense opportunities for change. Through his work, he is not only learning from his international colleagues, but he’s helping to lay the groundwork for a future where ophthalmic care is accessible to those who need it most. His hope is that his efforts, along with those of others in the field, will help make a lasting difference for underserved communities around the world.

Photos courtesy of Dr. Patrick Wurster.