Modeling epidemics is messy business. Transmission is random, even in the same disease. Behavioral dynamics, individual traits and randomness of transmission create layers of challenges.

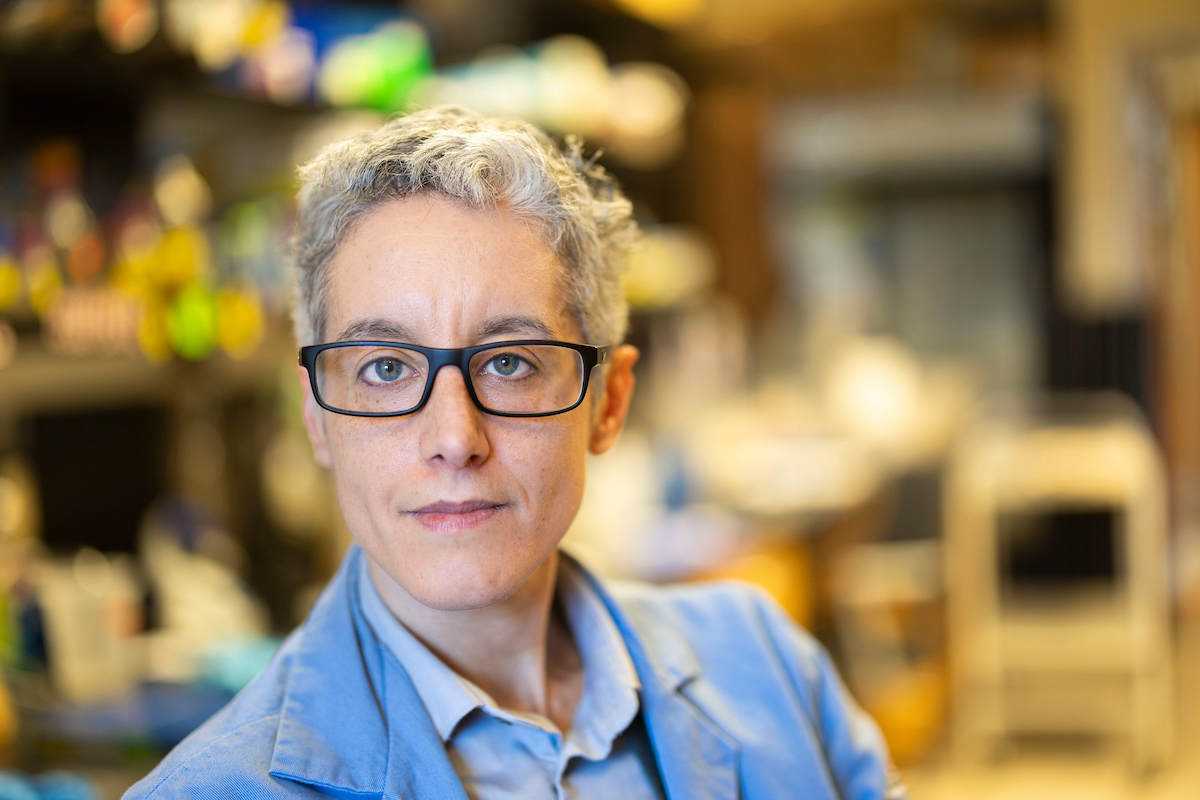

Enter the tiny roundworm C. elegans, the first multicellular organism to have its genome sequenced. Emory biologist Nic Vega has developed a novel system to study variables in outbreaks by creating a wide variety of controlled epidemics in the simple host.

The W.M. Keck Foundation has awarded Vega $1.2 million to study the ecology and evolution of transmitted diseases in this fast-paced experimental system. That data has the potential to build better models that predict transmission patterns and test interventions that may curb disease spread.

The project will run for three years and strengthen collaboration with Emory College’s physics department, where Vega is affiliated faculty, and the groundbreaking initiatives in the college’s Theory and Modeling of Living Systems (TMLS).

“Historically it has been challenging to model certain aspects of transmission, in part because variation is hard to measure accurately,” Vega says. “With worms, we can repeat an experiment over and over and see a broader range of outcomes of any given scenario.”

The project gets at a central statistical problem: Describing variation in living systems. Biological systems and real-world data about these systems are irregular in ways that can be hard to describe mathematically.

For the spread of disease, variation comes from sources such as variability in susceptibility due to genetics and life history — say one person’s immune system compared to another’s — and randomness in how an individual is exposed to the disease.

Vega’s project aims to control some of that noise, and generate better predictive models, by manipulating features such as the genetic variability of the worms and by accurately accounting for different types of transmission.

“This experimental system will let us generate very powerful data, and I am excited to see where those data will take us,” Vega says. “The hope is that this project moves us forward in understanding some of the basic rules for epidemics.”

The Keck Award will provide funding for the labor-intensive work, both in the lab and when collaborating on statistical models. Vega also plans to use the award to hire two postdoctoral scientists, a post-baccalaureate technician and two part-time undergraduate researchers.

“This is biotechnology work, because Nic is going to be able to make new genetic combinations of C. elegans in just weeks and assess an extremely large set,” says Steven L’Hernault, professor and chair of the Department of Biology.

“The prospect of understanding what aspect of the genotype may give you accelerated immunity or may give you elevated risk for any given pathogen is incredible,” L’Hernault adds.

The research is a new direction for Vega, who first began working with the worms to study the assembly of intestinal microbiomes.

That laid the groundwork for a project with Emory’s university-wide Molecules and Pathogens to Population and Pandemics (Emory MP3) Initiative, to develop a transmission model for bacterial pathogens.

Along the way, Vega and other scientists realized that some common mathematical problems with existing epidemic models were turning up when they tried to describe transmission in worms — even in experiments where most of the complications associated with human epidemic data could be avoided — and that fixing these problems required data that did not exist.

The features of the C. elegans that made them a common lab organism — genetic tractability, susceptibility to several bacterial, fungal and viral pathogens — made them an ideal focus for Vega’s new research.

The project also plays to Emory’s interdisciplinary efforts such as TMLS and strengths in both computational biology and population biology, says Anita Corbett, senior associate dean for research in Emory College and the Samuel C. Dobbs Professor of Biology.

“These are fundamental scientific questions being addressed, with real-life implications,” Corbett says. “This work highlights the collaboration at Emory that has the potential to set the stage for mathematical models that could help handle a future pandemic.”

About the W. M. Keck Foundation

The W. M. Keck Foundation was established in 1954 in Los Angeles by William Myron Keck, founder of The Superior Oil Company. One of the nation’s largest philanthropic organizations, the W. M. Keck Foundation supports outstanding science, engineering and medical research. The Foundation also supports undergraduate education and maintains a program within Southern California to support arts and culture, education, health and community service projects.