The day after our country held a contentious presidential election, a public forum of distinguished speakers discussed the nation’s sharp divide and how to heal it.

“After the Vote: Understanding and Repairing a Divided Nation” was hosted by Candler School of Theology’s James T. and Berta R. Laney Program in Moral Leadership and The Candler Foundry.

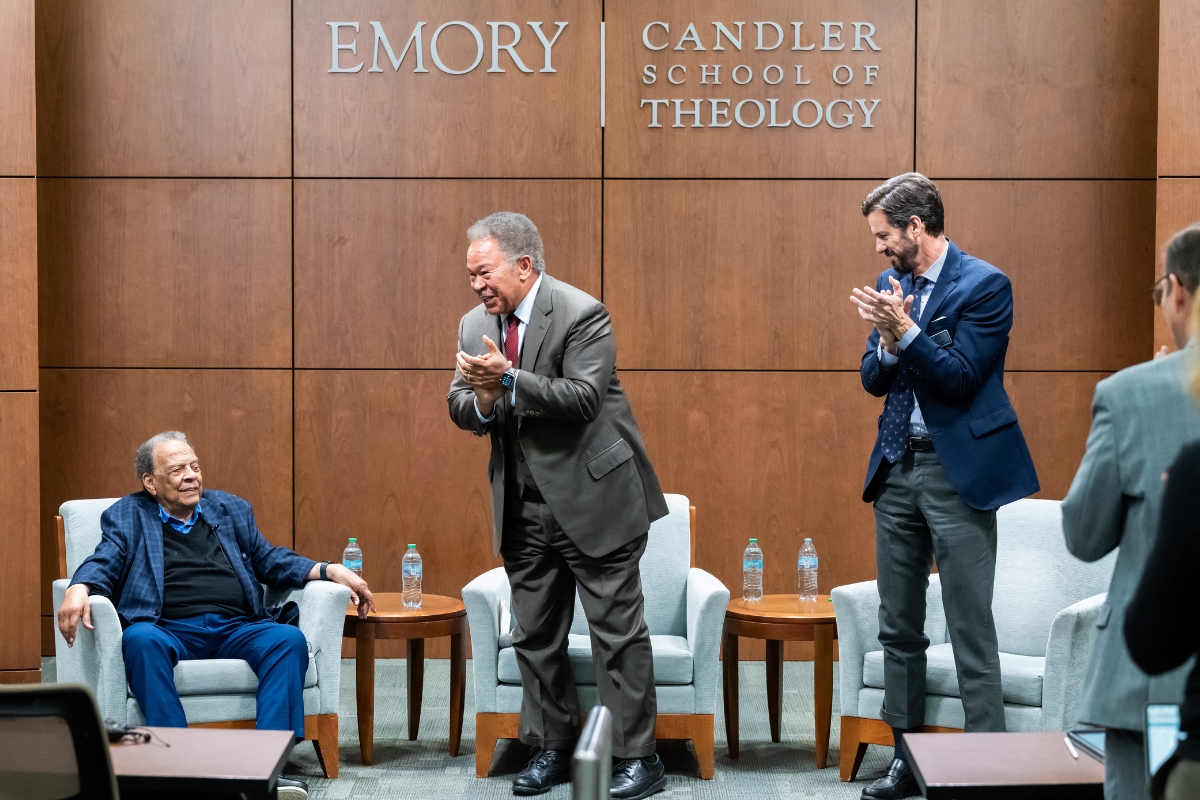

The panel featured Andrew Young, civil rights leader, former Congress member, mayor of Atlanta and ambassador to the United Nations; Joseph Crespino, Jimmy Carter Professor of History; and Andra Gillespie, associate professor of political science and director of Emory’s James Weldon Johnson Institute for the Study of Race and Difference. Robert M. Franklin Jr., Candler’s James T. and Berta R. Laney Professor in Moral Leadership, moderated the event.

A nation divided

The divisiveness that defines today’s political sphere arose little by little, according to the panelists.

Gillespie noted that until 1987, the Federal Communications Commission required television broadcasters to present controversial issues in a way that reflected differing viewpoints. The repeal of this requirement, she said, led to the rise of both partisan media and, eventually, disinformation on social media, where many people get their news today.

Until recently, Gillespie said, even partisan coalitions consisted of people with overlapping interests across the political spectrum. But today, she said, instead of lawmakers forging alliances across the aisle, “we have people on the extremes who don’t want compromise.”

Similarly, Crespino noted, “We're much more likely today to live in neighborhoods where we just have no interaction with people who see the world differently than we do or see politics differently than we do. And that accelerated so much in the era of social media.”

In sharp contrast, 92-year-old Young pointed out that, as a child in New Orleans, he grew up amid many nationalities and prejudices. Joking about how this upbringing trained him for his later career as a U.N. ambassador, he quipped, “I mean, I knew about the United Nations before Ralph Bunche did!” (Bunche, a U.N. mediator, famously won the Nobel Peace Prize for diplomacy in 1950.)

Community despite difference

Young went on to tell how he went out of his way “to speak with all the racist congressmen” during his time serving in the U.S. House of Representatives. He also attended prayer breakfasts that mostly included lawmakers from the opposite side of the political spectrum, and described how he led the group in prayer for the family of Vice President Spiro Agnew during a time of crisis, prompting surprise from some members. This outreach to unlikely allies paved the way for later political progress.

“There’s something in the American ethos that responds to the strength of moral force,” Crespino said earlier in the event, quoting Martin Luther King, Jr. to praise Young’s work. “That’s hard to believe today. But you and Dr. King never lost your faith in the power of moral force. To me, that is a memory of hope that I will hold onto.”

Crespino’s words prompted a standing ovation for Young.

Panelists also pointed out that the necessary work of knitting our fragmented society back together doesn’t mean we must all be activists all the time. People also need to give themselves credit for rearing children, caring for aging parents and taking care of themselves.

“Freedom is constant struggle, but you can’t be in every fight,” Young said.

But all of the panelists agreed that even small actions are crucial and that everyone can make a difference.

This semester, Crespino is teaching a course on political polarization in the 2024 election cycle, including students with a variety of political opinions. “We've had some difficult conversations and one of the things that we’ve talked about … is we need to learn how to disagree with people in civil ways.”

And that needs to occur beyond classrooms, too. “I think the way we’re going to have to move forward is creating community despite difference and being intentional about it,” Gillespie said.

The panelists offered a number of ways to do this. It could mean acknowledging when our political heroes get things wrong or when someone from a different political party has a good idea. It may be as simple as introducing ourselves to a classmate sitting next to us or inviting a colleague sitting alone to lunch. Or becoming friendly with neighbors who think differently than you do and carving out spaces for genuine community that don’t have anything to do with politics.

Young, who began his career as a minister and still preaches, told the audience’s faith leaders and seminary students that their job is to “build a family on campus” — and then to “expand that family to include everyone you know.”