A sculpture of cupped hands raising a tree skyward greets those who enter Science Gallery Atlanta’s newly opened exhibition, “Resilient Earth.” Setting the tone for the exhibition’s theme, the work is made entirely of reclaimed materials by artist William Massey. Just around the corner, thousands of plastic water bottles collected from throughout metro Atlanta form winding, multicolored walls.

Running through April 30, 2025, “Resilient Earth” marks Science Gallery Atlanta’s first show in its new location at Northlake Mall. Through its fusion of art and science, the exhibition invites viewers to consider imaginative approaches to sustainability in ways big and small.

“We’ve come up with an exhibition that starts where people are and asks them to reflect on their lives and how they might live more sustainably,” says Alexis R. Faust, executive director of Science Gallery Atlanta, an arm of Emory’s Office of the Senior Vice President for Research.

“Resilient Earth” consists of 13 installations — including seven led by members of the Emory community — developed in partnership with various artists; Accenture, an international IT and consulting company; and Shibui Design, an Atlanta firm specialized in creating immersive environments.

The plastic bottle installation, titled “ECOLECTIVOS: A World Wrapped in Plastic,” was led Lisa Thompson, professor in the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, and Eri Saikawa, Emory professor of environmental sciences. Its design also features bottles stacked into the shape of a fireplace. A video details how Emory researchers are working with communities in rural Guatemala to find alternatives to burning plastic waste for basic household needs, such as heating and cooking.

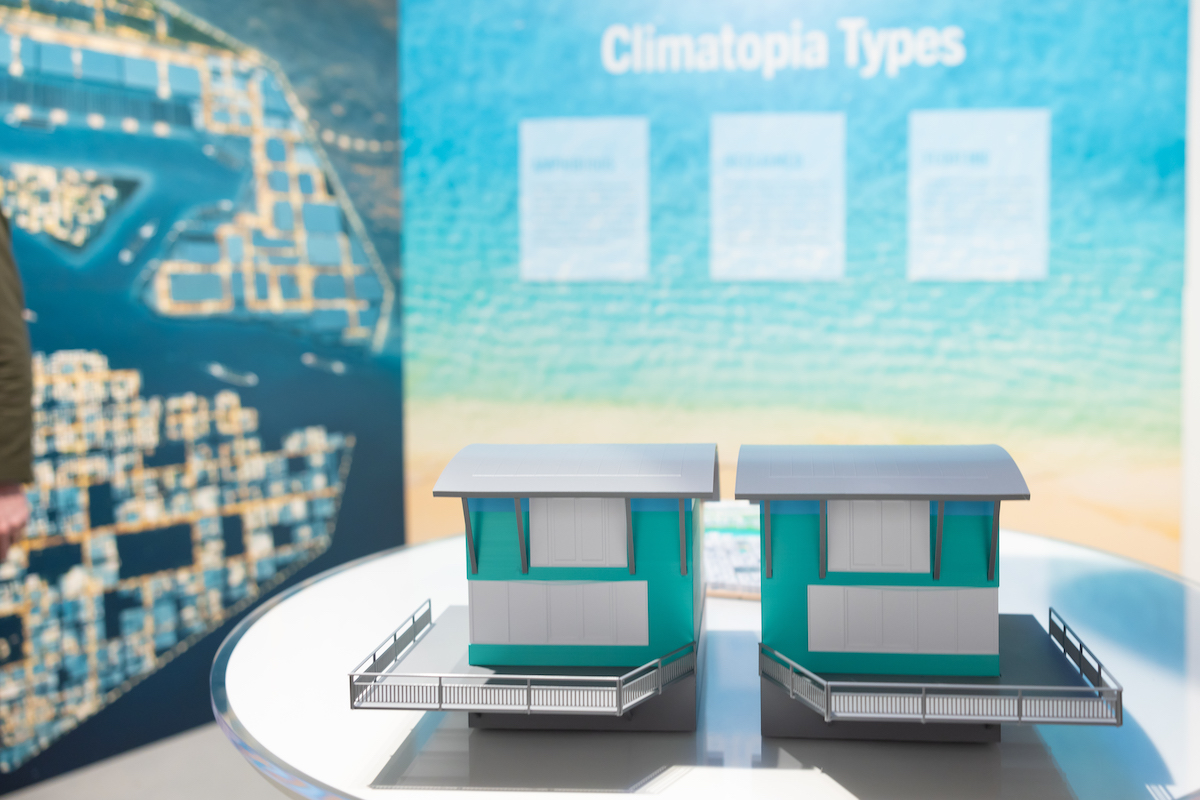

Jola Ajibade, Emory associate professor of environmental sciences, focuses her research on examining the resilience of coastal communities to climate change. She served as the lead on an installation titled “Floating Climatopias: Futuristic Designs for Flood-Resilient Settlements.” Its centerpiece is an example diorama of a settlement, accompanied by descriptions of other real-life floating climatopias developed in response to rising sea levels.

Science, art and self-reflection

A key goal of “Resilient Earth” is to inspire serious self-reflection by visitors on issues of sustainability, Faust says.

“One of the biggest challenges about discussing climate change today is how polarized and political it is,” Faust says. “We are asking people to reflect on what’s important to them. At the end, we ask them to make a pledge: Are they willing to do something differently or better in the future?”

Essential to this vision are the gallery’s 22 student mediators. They guide visitors through the exhibition by both answering and posing questions.

“They’re not there to tell you what the exhibit is or what to think,” Faust says, “but to have conversations, spark inquiry and be a point of reference.”

Mediator Isabella Perago — an Emory senior studying neuroscience and behavioral biology and integrated visual arts — is fascinated by the relationship between art and science. She enjoys helping viewers contemplate the exhibition in relation to their own experiences.

“I’m excited to facilitate conversations that help further people’s understanding of the importance of what each of these [installations] has to say,” Perago says. “They’re all distinct, but there’s a really cohesive element.”

Faust explains that when scientists and artists collaborate, a kind of “creative collision” can take place, allowing a visitor to engage — and in many cases directly interact — with complex ideas and processes dealing with, here, sustainability. She adds that the collaboration can transform a scientific report into an emotional experience.

“It’s a moving exhibition, as you’ll see when you walk through it,” Perago says.

Many of the installations have a quiet and meditative tone that encourages self-reflection.

“Having them at that [figurative] decibel level is important, because it’s the opposite of what many conversations [about sustainability] end up being — which is highly charged and emotional,” Faust says. “So, this takes it down a notch. Let’s have a human conversation, person to person, and just keep it calm and reflective.”

An installation called “Sacred Breaths” is inspired by forest-bathing — an ancient practice of immersing oneself in the sensory elements of nature — and projects by Saikawa’s lab to measure air quality around metro Atlanta. Saikawa, who was also a lead in the “ECOLECTIVOS” installation, collaborated with California artist Bea Lamar to create a greenhouse full of plants native to Georgia. Visitors can step inside the greenhouse, where its lights change color in response to air quality.

Open minds

The last installation before exiting “Resilient Earth” is “Thermal Reverberations,” a collaboration between Amanda Jacob, an Emory associate scientist in the biology department, and artist Craig Coleman.

Like the earth itself, the human mind changes based on the activity around it, Jacob notes. “Thermal Reverberations” illustrates this through a table layered with thermal paint that responds to the heat of human touch and models of brains that change color the closer one gets to them — again in response to body heat.

Jacob sees the installation as a hopeful illustration of adaptation.

“Our exhibit is about our ability to change, particularly how our brains change,” she says. “That can be changing your minds or your views, but it’s also suggesting ways we biologically are able to change throughout our lives. In our case, you can literally touch the exhibit and see a demonstration of what we want to suggest.”

The exhibition, Faust says, aims to channel the same sort of optimism inherent to Jacob’s installation — to strike positive notes with those who contributed to its creation, the students serving as mediators and the community members who visit it.

These goals closely align with Science Gallery’s overall mission, Faust adds.

“We really would like to have people think about us as a community learning center, as a place where you can go that’s safe and comfortable to have conversations that are maybe a little bit scary. You can come here to learn.”