The Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library welcomed Joan Browning and Charles Person, two participants in the 1961 Freedom Rides during the civil rights movement, to Emory this summer.

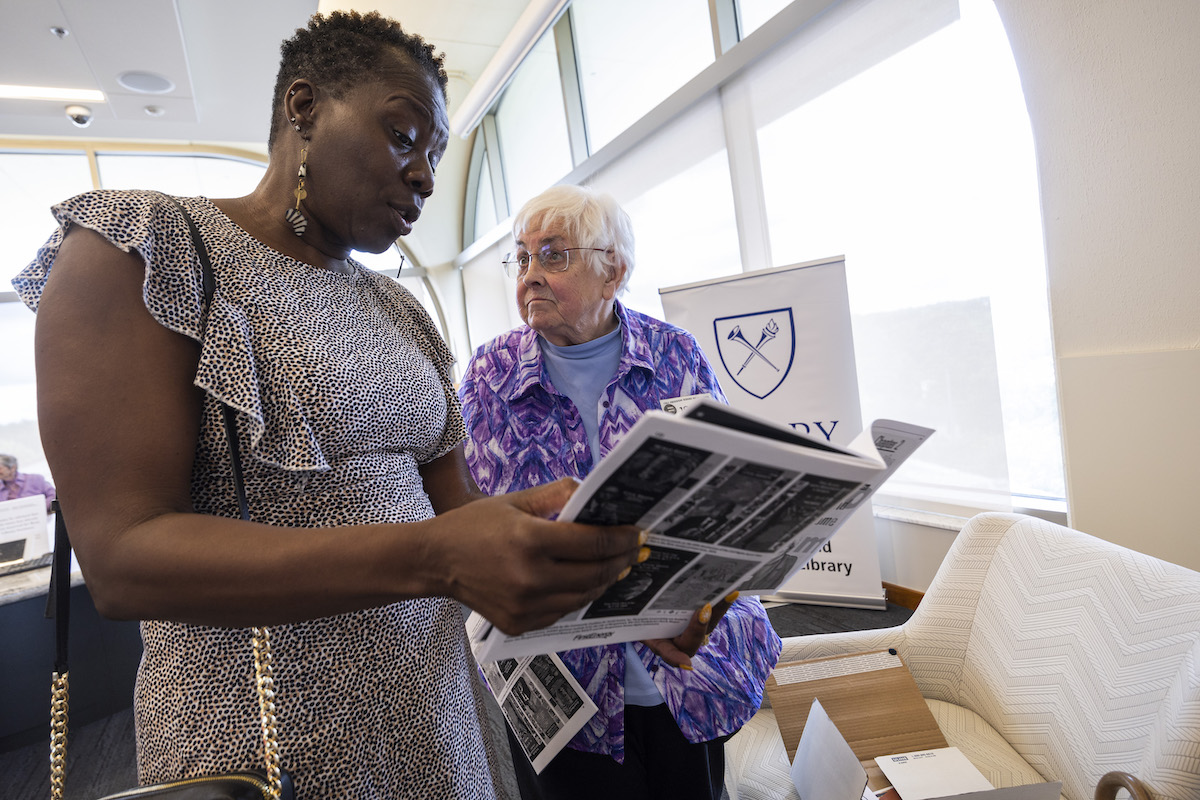

Various members of the Emory community joined them on the top floor of the Robert W. Woodruff Library on Friday, July 26, to browse through historic documents and items from Rose Library’s African American History and Culture Collection, along with documents from Browning’s personal papers, already in the Rose’s collection.

While the group perused the items, Person announced that he would be placing his personal archive with Emory.

“The Rose Library is delighted to have the papers of Freedom Riders and civil rights activists because these documents show how it was everyday people — many of them teenagers and young adults — who led the civil rights movement and changed the world,” says Carrie Hintz, interim co-director of the Rose Library. “It is powerful for our students and researchers to hold in their hands the evidence of how other young people who were living in a difficult and complex time fought against the oppressive systems of their moment to shape a new future.”

Person, born and raised in Atlanta, was the youngest participant in the very first Freedom Ride of 1961 from Washington, D.C., to Birmingham, Alabama. He was only 18 years old. In addition to joining the Freedom Rides, Person also participated in sit-ins during his time as a student at Morehouse College in Atlanta.

Browning, who also hails from Georgia, became involved in the Freedom Rider movement while attending what is now known as Georgia College & State University. As a white woman, she was dismissed from the school in 1961 for attending a Black church during her involvement in the civil rights movement. Nearly the same age as Person, Browning joined the Albany Freedom Ride and was jailed.

“Many people ask if participants in the Albany movement followed Martin Luther King Jr. to jail. Well, we were arrested on Sunday, and he didn’t go to jail in Albany until Friday,” said Browning with a smile. “With all the influence of youth, we say, ‘He followed us to jail!’”

Though they never were on the same Freedom Rides, Person and Browning met after the civil rights movement at reunions held over the years for Freedom Riders. To date, there are estimated to be fewer than 50 riders remaining across the country, down from 436 who initially participated.

“We were bonded to each other, and we remain that way to now,” said Browning. “This is my family, the people that I was with at the time, and we were committed to a joint project.”

You’ve got to do something in life. You might as well do something meaningful.

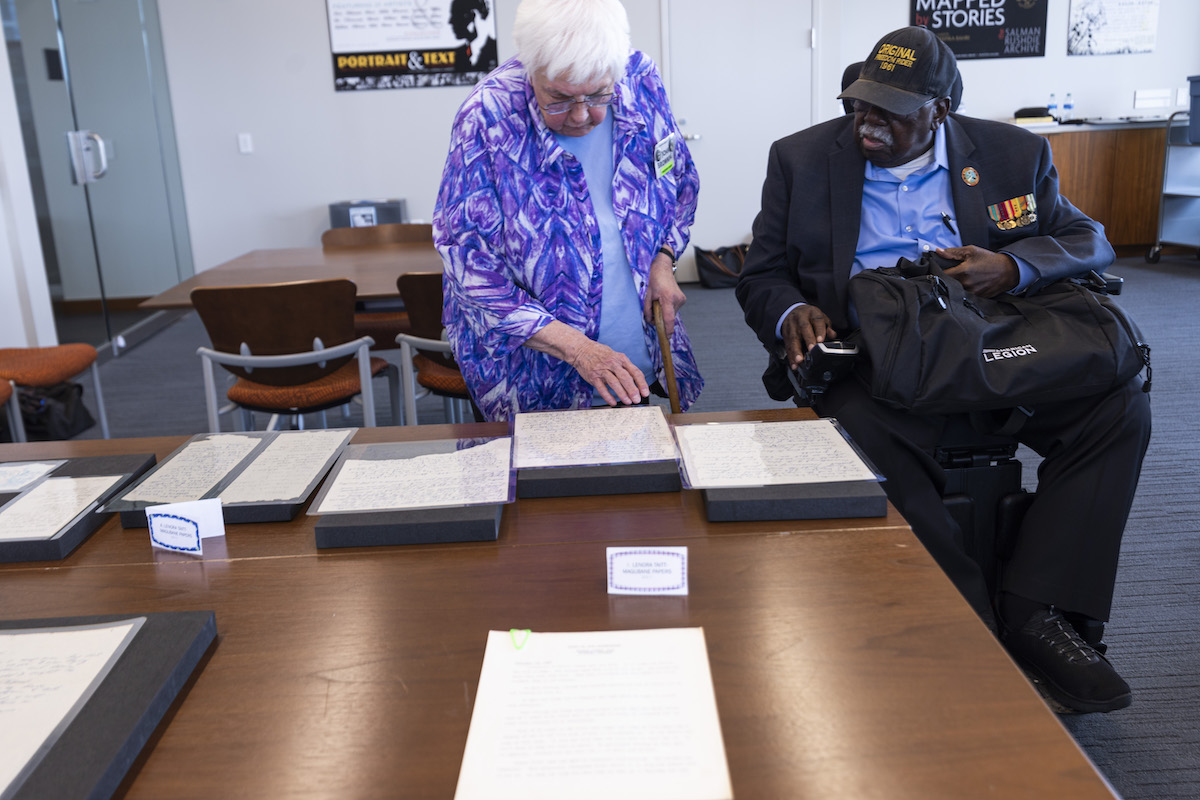

Before sitting down for a conversation, Browning and Person browsed a room full of documents and artifacts from several collections, telling stories about their role in and memories of the civil rights movement.

Included in the display were notes written on toilet paper exchanged in the Albany jail among Browning and activists A. Lenora Taitt-Magubane and James Forman.

Members of the library staff read from a toilet paper letter written by Browning in the collection: “Spirits over here are fine … We have found a name for our present residence. Over my door is, ‘Welcome to the Crossbars Hotel.’ Keep the chins up — we are still winning. Love to all, Joan.”

Another scrap of toilet paper boasted Martin Luther King Jr.’s personal phone number. Browning noted how King was incredibly accessible to everyone in the movement.

Person didn’t have paper while in jail, so he and other Freedom Riders would sing while detained instead of writing. In fact, Person was placed in solitary confinement for 10 days for singing too loudly.

“We sang freedom songs anyway because it exuberates you,” said Person. “The songs not only encouraged us, but it was also a way of relaying messages. We changed or modified the verses to let other people in jail know what was going on, how many people were there, if any members of the clergy were going to visit, things like that.”

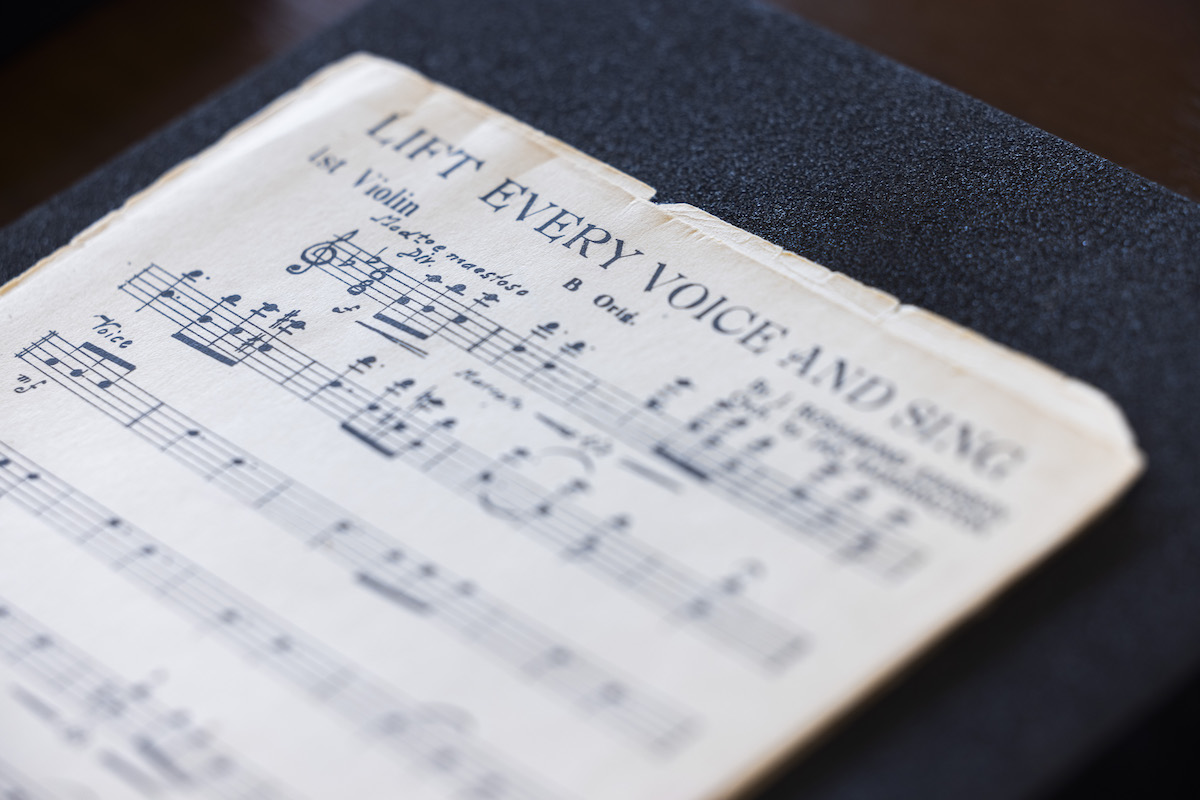

One notable object stood out among the paper items. The staff pulled the typewriter on which “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” known as the “Black National Anthem,” was composed by NAACP leader James Weldon Johnson. “Lift Every Voice and Sing” was one of the protest songs that Freedom Riders sang in jail.

After viewing the archive items, the group moved to the Woodruff Seminar Room to continue the conversation. There, Browning and Person emphasized their joy in sharing their experience with members of the younger generation.

“I emphasize how young we were during the movement. Young people can really make a difference and make the world a little better,” said Browning. “You’ve got to do something in life. You might as well do something meaningful.”

Person also gave his perspective on the importance of young people being bold enough to act on the ideas they are passionate about.

“They have the ability to change the world. They have many great ideas, but they have doubts about how far they can go. I like to give them the courage,” said Person. “When I first met Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis and a lot of other members you all know, they weren’t famous. They were doing things that would eventually make them famous.”

To view the African American History and Culture collection and the many others held by the Rose Library, visit the website for detailed instructions on scheduling a visit.