Far beyond their church-based roots, the music of historical spirituals, gospel songs and other hymns reverberates throughout popular culture.

Think of movies such as “Titanic” (“Nearer My God to Thee”), “O Brother, Where Art Thou?” (“Down to the River to Pray,” “In the Highways”), “Sister Act” (a rousing version of “Salve Regina”) and many other films whose soundtracks linger long after the credits roll. And even well-known hymns such as “Amazing Grace” and “O Come All Ye Faithful” have been reimagined countless times, with multiple shifts in styles in the decades since they were written.

For years, the Sounding Spirit Collaborative, an initiative managed through the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship (ECDS), has digitized 1,300 sacred songbooks published between 1850 and 1925. Now the project has received a $349,929 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), the Collaborative’s fourth NEH grant, to create the Sounding Spirit Hymnody Index.

This massive undertaking will document the 300,000 settings of hymn tunes and texts in these books and make this information discoverable for both researchers and the public — particularly church music practitioners looking for new choral songs and arrangements.

Sounding Spirit is a collaborative composed of ECDS, the University of North Carolina Press and seven partner archives, including Emory’s Pitts Theology Library and Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library as well as others across the country. It promotes publishing, research and teaching with the sacred songbooks that were popular across the southern United States during this active period of American history.

Jesse P. Karlsberg, project director and editor-in-chief, also serves as a senior digital scholarship strategist at ECDS and an associated faculty member in the Department of Music at Emory University.

The new searchable index will make research easier, he says, by documenting the hundreds of thousands of hymns in the songbooks that the partner institutions have contributed and logging all of the titles and their variations, along with authors, publications and dates, locations, religious denominations and other details.

“These grants have allowed us to piece together a big part of religious and music history in America,” Karlsberg says. “By indexing the materials from our partner institutions and allowing researchers to cross-reference their contents, we can learn so much about how hymn tunes and texts moved around the country, crossed into other denominations, and were even adapted into popular music like gospel, blues and other genres.”

The Sounding Spirit project team also includes four Emory graduate students and three graduate students at other partner institutions; a part-time Emory project manager; a staff member at the Pitts Theology Library; and other ECDS staff.

“The Sounding Spirit project uses digital technologies to connect communities of historians, scholars, musicians, students and other users to historical sacred music across decades,” says Valeda F. Dent, vice provost of libraries and museum. “We are delighted that the NEH continues to support this important project and grateful that we have a top-notch team of experts and scholars who continue to shepherd this effort.”

The project’s first grant, received in 2018, funded initial work on the project’s forthcoming series of print and digital scholarly editions of select sacred songbooks. It then received two additional grants in 2019 and 2021 to support the creation of Sounding Spirit’s Digital Library, which involved digitizing the 1,300 songbooks and recording metadata including book titles, dates, creators and areas of origins or use.

This upcoming phase will delve into the digitized songbooks, most of which contain hundreds of discrete hymn texts and tunes. By recording these texts and the tunes’ melodies, and by documenting their authors and composers, the project will enable researchers to make connections necessary for their work and teaching.

Meanwhile, the team continues to work on building the Sounding Spirit Digital Library.

“We’re thrilled with the work of the Sounding Spirit Collaborative initiative,” says Allen Tullos, co-director of ECDS. “With Jesse’s leadership and the resounding support of the NEH, this extraordinary project continues to make musicological history through its application of digital methods to a rich and diverse archive of American musical composition and performance.”

For research, teaching, choral singing and public enjoyment

Most similar research focuses on hymns from earlier periods. Sounding Spirit, however, covers 1850 to 1925, a time frame that has largely been left out of prior hymnody indexing projects. By recording the hymns, gospel songs and spirituals sung by Black, Indigenous, and urban and rural white congregations across the U.S. South and its diasporas, the project reveals how sacred music from this era crossed racial lines, religious denominations and musical genres.

Karlsberg said this period is fascinating not only because is it somewhat neglected by researchers in favor of earlier eras, but because it was a time of great social change. The Civil War, the Great Migration and rural-to-urban migration, and the rise of Black Christian denominations and Pentecostalism all contributed to the geographical spread of tunes that were once limited to smaller and specific areas of the country.

Set to begin this fall, the indexing project will be beneficial to more than just researchers and instructors who hope to find, compare and use hymn tunes and texts.

The completed index will also make the collections more accessible to the public, who will be able to search for different settings of hymn texts or varied arrangements of beloved hymn tunes — sometimes even the original versions.

Among those who will find these tunes and texts valuable to their modern practices, Karlsberg says, are congregations, choral ensembles that perform spirituals and other sacred music; those who participate in gospel conventions and fan networks; and shape-note singers, whose community singing style draws on 19th-century American traditions.

Used by researchers — and choral singers

Ian Quinn is a music professor and the chair of the music department at Yale University as well as the co-editor of the forthcoming “Oxford Handbook of Music and Corpus Studies.” He intends to use the upcoming Sounding Spirit Hymnody Index in his teaching and research to perform a quantitative analysis, exploring how the vernacular music styles in the index cross racial and cultural lines.

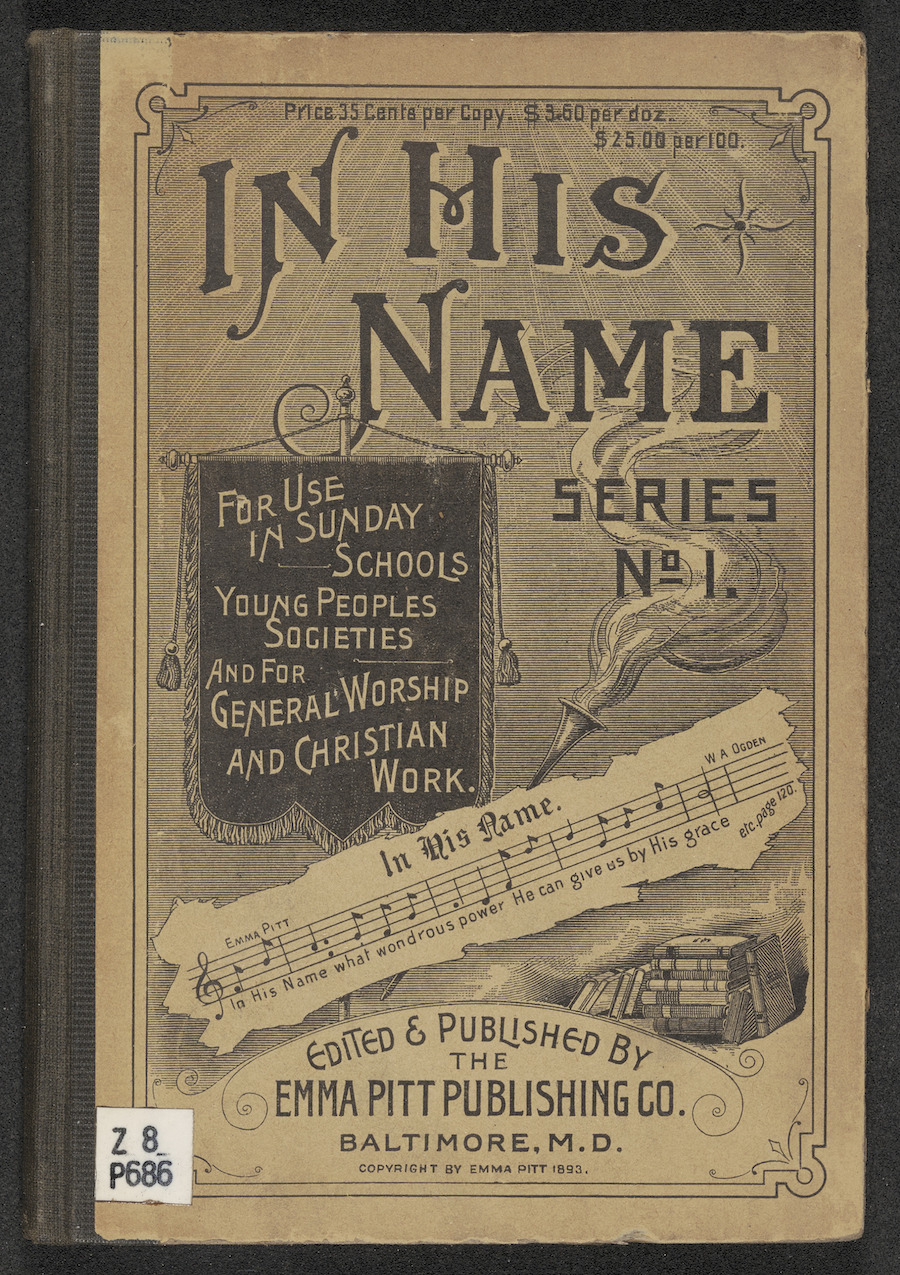

“In His Name,” edited by Emma Pitt (1893), published by the Emma Pitt Publishing Co. of Baltimore, Maryland. Sounding Spirit documents the active role members of marginalized populations played in southern sacred music publishing, including through the inclusion of songbooks with women authors and editors such as this book, one of eight in the digital library edited by Baltimore composer and songbook editor Emma Pitt.

“Sounding Spirit’s greatest promise is to make available the printed cultural archive of this exchange that is otherwise documented only by verbal witness accounts whose language is inadequate to the task,” Quinn adds. “This dataset will allow me to use mathematical modeling to observe the traces of the cultural forces that guide the transmission of musical ideas through this network, and to tell the story of individual tunes within this rich intercultural context.”

Derrick Fox is a professor of choral music and the associate dean of graduate studies, research, and creative endeavors at Michigan State University’s College of Music. He plans to use the Sounding Spirit Hymnody Index to aid in his research and teaching, which focuses on choral arranging and conducting and shape-note singing in African American communities in the South. He has also composed choral arrangements of Southern shape-note tunes and hymns and taught them to various age groups to spark interest in the music of marginalized populations.

“I am always delighted by the shock that comes forward when graduate students become aware of the existence of shape-note singing practices within Black American communities in the U.S.,” Fox says.

“Sounding Spirit is a valuable resource for expanding my students' awareness and knowledge of the diversity of practices within marginalized communes in the U.S. I can share with them the music-making practices in Black and Indigenous communities that further challenge the traditional boxes that have been drawn for them to categorize choral singing and culture.”

Value for graduate students

ECDS has long excelled at providing professional experience for graduate students across Emory. The Sounding Spirit project has several graduate assistants working on various aspects — assessing the condition of songbooks, researching and recording information about the books, cleaning and processing this data, and developing teaching materials. Now, graduate students will help build the Hymnody Index to guide myriad paths of ideas and connections.

Em Nordling, a PhD candidate in Emory’s Department of English working on Sounding Spirit at ECDS, says making the vast collection of materials discoverable and accessible to researchers and the public allows graduate students to make a significant contribution.

“We’re digitizing items that have been, for many decades, inaccessible to both the communities that produced them and the researchers working to highlight their histories and contributions,” Nordling says.

“Now, indexing the hymns, we’re broadening opportunities even further for users to make connections between specific contributors and publics, and cultural and geographical movements.”

As a research data associate, Nordling works with the team to produce clean, usable data for researchers across disciplines.

“I have found a lot of value in working on this project as a grad student. For one thing, humanities research can sometimes be very individual and isolating, so it has been amazing to work with a team of other passionate people,” they say. “It has also helped me to make connections within the world of digital humanities, shaping the kinds of questions I ask in the digital portion of my dissertation as well as the path I’m planning for my post-PhD career.”

A long-running project with big goals

For those who will use the Sounding Spirit Hymnody Index for research and teaching, this new initiative of the Collaborative will become a major resource, documenting tens of thousands of songs and their variations and journeys across cultures and denominations over the decades.

This latest grant brings the total funding Sounding Spirit has received from the NEH to more than $1 million. This level of support “is amazing for a humanities project,” says Karlsberg. “This is an outstanding level of success that we've had.

“By the end of this grant, it'll have been nine years since Sounding Spirit began. These hymn tunes and texts were so important to how people navigated life in the period I study, and they continue to be meaningful to people today,” Karlsberg says. “I'm really excited about the work we are poised to do to share this material with researchers and the public.”

To learn more about the project, visit the Sounding Spirit website.