In May, four scholars of writer Flannery O’Connor gathered on Level 3 of the Robert W. Woodruff Library to walk through the exhibit “At the Crossroads with Benny Andrews, Flannery O’Connor and Alice Walker.” Two of those experts happened to be Hollywood royalty.

Director and actor Ethan Hawke and his daughter, actress Maya Hawke, recently released the film “Wildcat,” which Ethan directed and co-wrote and in which Maya stars as O’Connor. Ethan has been nominated for four Academy Awards, twice as a writer and twice as Best Supporting Actor. Maya made her acting debut in the BBC miniseries adaptation of “Little Women” and currently stars in Netflix’s “Stranger Things.”

They were there to rub elbows with, and learn from, royalty of Emory’s own — “Crossroads” co-curators Gabrielle Dudley, Rosemary Magee and Amy Alznauer.

Coming to the ‘Crossroads’

The exhibit chronicles the overlap that these three Georgia artists — Andrews, O’Connor and Walker — experienced geographically, chronologically and creatively. The Emory Libraries is, in fact, the physical crossroads to explore the lives and careers of the artists beyond the exhibition: the papers of Benny Andrews, Flannery O’Connor and Alice Walker all reside in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library.

The Hawkes proved attentive listeners, keyed to all that Magee and Alznauer, co-curators for the O’Connor section of “Crossroads,” imparted. Under glass, and commanding admiration from the Hawkes, was the large-format book Benny Andrews illustrated of O’Connor’s “Everything That Rises Must Converge” — a story central to the exhibition and the film.

Magee, an expert on Southern women writers, is editor of the book “Conversations with Flannery O’Connor” and director emerita of the Rose Library. Alznauer is the author of “The Strange Birds of Flannery O’Connor: A Life,” which was named a New York Times Best Children’s Book of 2020 and a 2022 Book All Young Georgians Should Read.

Just prior to their arrival at the exhibit, Ethan had been city-hopping to promote the film, while Maya worked on set in Georgia filming “Stranger Things.” The pair were welcomed by Dudley (who is serving as co-interim director of the Rose Library), Magee, Alznauer and a small group of library staff.

Ethan confessed that he had just awakened from 12 hours of sleep following what he termed “one of the busiest weeks of my life,” which involved dodging tornadoes in Tulsa, Oklahoma; Q&As on both coasts; an interview on “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert”; and time with his children in New York.

The Hawkes spent the better part of an hour asking questions and absorbing, with obvious delight, the exhibit’s rare archival photos, journals, letters, original manuscripts and artwork, as well as personal artifacts. They then participated in a Creativity Conversation, led by Magee and Alznauer, that followed a showing of the film at the Tara Theater that afternoon.

The roads leading to O’Connor

As the Creativity Conversation got underway, Ethan noted to the standing-room-only crowd, “Maya and I have talked about this movie, and about O’Connor, a lot. It is a real honor to be with two people who know more about this subject than we do. I find it both exciting and nerve-wracking.” To laughter, he then added, “Am I being set up?”

The Hawke family’s admiration of O’Connor runs deep, beginning with Ethan’s mother, who moved her son to Atlanta in 1980 and “fell in love with Flannery O’Connor while we were living here. I thought O’Connor was the foremost author in America because that was what my mother thought. She used O’Connor, in part, to conjure the inner feminist in me,” he recalled.

Maya became riveted by O’Connor in high school, eventually convincing her father to pursue a film about the Southern Gothic author whom writer Richard Gilman, a friend of O’Connor, pronounced “tough-minded, laconic, with a marvelous wit and an absolute absence of self-pity.”

Asked by Alznauer what had drawn her to O’Connor’s story, Maya commented, “O’Connor lived through her art. You can travel so far and see such incredible things by viewing the world through your imagination. As a young person, I was always writing stories, poems and making paintings. Art connects you to something greater than yourself even when your freedom is stunted — in Flannery’s case, by lupus.”

The first emergence of the artist

Alznauer and Magee noted that age 15 had been formative for the three “Crossroads” artists. In the case of O’Connor, 1941 was consequential for Pearl Harbor being bombed and, more personally, for its being the year that O’Connor’s father lost his own fight against lupus. Magee noted that in order to cope, to carve out her identity, O’Connor at that time, as she phrased it, “was focused on bringing literature into being.”

Maya indicated that she was indeed 15 when she first encountered O’Connor’s work and, in that same year, won her first role in a school play. Ethan cheerfully accepted late-bloomer status, having produced his first published work, “The Hottest State: A Novel,” in 1996 when he was 25.

“That was extremely scary for me. I couldn’t imagine living beyond it, living through the criticism,” he said. It might surprise readers more familiar with Ethan’s Hollywood oeuvre that he has published four other works — three novels and a history — in the succeeding years, the most recent being the semiautobiographical “A Bright Ray of Darkness: A Novel” in 2021.

Imagination = reality

“Wildcat” is titled after an early short story by O’Connor that was included in her 1947 master’s thesis — pursued in creative writing at what is now the University of Iowa — “The Geranium: A Collection of Short Stories,” which was not published until after her death.

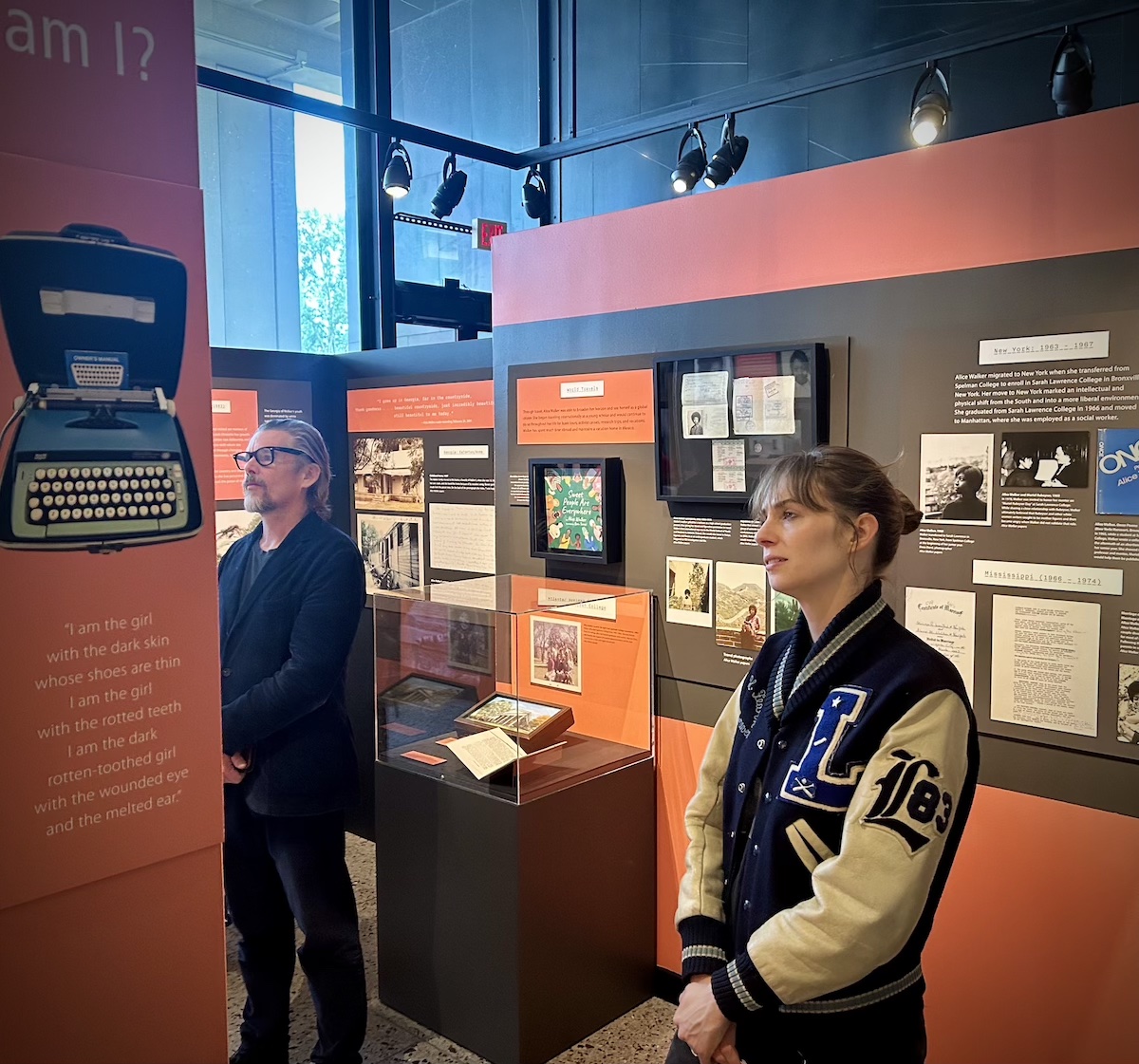

Ethan and Maya Hawke appeared as just another set of grateful visitors to the Emory Libraries’ “Crossroads” exhibit, which they toured prior to screening their film “Wildcat” at the Tara Theater. Here, they are taking in the Alice Walker section of the exhibit.

As Maya reflected, “Flannery didn’t lead a cinematic existence — have a grand love affair or climb a mountain. Figuring how to insert plot in a life that didn’t have any was a difficulty until my dad had the idea to tell her story through her own investigation of her inner life. He wanted to weave in the fiction of her life with its reality. Her writing was as real as life got to her.”

The structure of the film alternates between scenes from O’Connor’s life and dramatizations of several of her most well-known stories, with the principal actors having roles in both worlds. As Maya noted, “Familiar characters start to pop up in the stories, even if they have different names. The most common characters were those who resembled Flannery and her mother, Regina.”

“Imagination equals reality is the equation the film is based on,” Ethan said. “The way we shot the real world and that of her imagination was similar, with slight variations. I wanted this film to feel like a fever dream.”

O’Connor had a famous take on these two realms of existence, saying: “I am always irritated by people who imply that writing fiction is an escape from reality. It is a plunge into reality, and it is very shocking to the system.”

A signal moment in the film comes when O’Connor’s mother visits her in the bedroom where she would type out her fiction in front of a window overlooking their farm. When her mother comments that she is lucky to have such a nice view, O’Connor revolts the moment she is alone again. She painstakingly, especially given the extent of her physical deficits by then, stacks all the heavy furniture in front of her desk so that she now will write before a wall, her back to the window.

“Her faith is made manifest in the way that she turned her life into little parables. Twenty-four years old, diagnosed with lupus, stuck in Milledgeville. How do you get not only to acceptance but to ‘I don’t even have to look out the window’? That struck me,” Ethan said.

The question of race

O’Connor’s racism is something that both the film and the “Crossroads” exhibit confront.

Alznauer noted that some of O’Connor’s early stories, “White Girl” and “Frizzly Chicken,” explored how children learn to be racist. She continued, “I hear her talked about as a product of her time, but I think that both gives her too much credit and too little credit. She was incredibly self-aware of her own deficits.”

Ethan acknowledged coming to see her racism more gradually as he absorbed her fiction, but stressed, “That is not a reason to stop talking about her.”

He then turned the conversation back to “Crossroads,” saying, “That is why your exhibit is so moving, to see O’Connor’s picture up alongside Alice Walker’s. It is astonishing that Alice Walker, who has taught us so much about racism, lived down the road from Flannery O’Connor and they never met. But that’s our country. For my part, I thought it was important to hold Flannery accountable yet forgive and love her.”

“Everything That Rises Must Converge,” the collection of stories O’Connor penned during the final decade of her life, was set amid the high-water mark of the civil rights movement and reflects, according to Magee, “O’Connor coming to terms with her own life, her own prejudices and her own death.”

Maya rejected the idea that making a movie about O’Connor is inherently a celebration of all she represented. Instead, she sees “Wildcat” as an exploration that “has enabled me to have more conversations about race, with people of all skin colors, than I ever have had in my life. I have learned things and found common ground."

The composers assuredly ‘scored’

A potentially overlooked gem of the film is the unconventional music.

Alznauer asked about it, saying: “One of the most seductive and haunting aspects of this film is this strange music that allows us to go from fiction to reality and confers a spiritual, ethereal quality.”

Ethan entrusted that aspect of the film to his co-writer Shelby Gaines and Gaines’ brother, Latham. Ironically, O’Connor had no use for music, despite its use in the Catholic faith with which she identified so strongly.

Counting on the music to link the scenes of reality and imagination, Ethan had the audience laughing when he revealed that “I wanted the music to approximate prayer, so I presented the composers with this challenge: What does the Holy Spirit sound like?”

Noted for creating “sound sculpture from found materials,” the Gainses had first worked with Ethan on a revival of the Sam Shepard play “A Lie of the Mind.” For “Wildcat,” the brothers built their own instruments, using farm utensils in some cases.

“What might sound like a blues guitar is the radiator of a ’52 Ford played with a violin bow,” Ethan contended. “In some sense, what you hear is not music; it is the sounds of her inner life.”

The last word goes to?

O’Connor had a special love for birds, having achieved some measure of fame by, at the age of five, having Pathé News come film a segment on the chicken she had taught to walk both forward and backward.

As she drolly noted later, “My chicken’s fame had spread through the press and by the time that she reached the attention of Pathé News, I suppose there was nowhere left for her to go — forward or backward. Shortly after that she died, as now seems fitting.”

And while O’Connor playfully suggested of the peacocks wandering her farm that, “in the end, the last word will be theirs,” it is instead her words that reverberate.

Ethan suggested that “her last six or seven stories are on another level. Each one of her characters is an aspect of the self. To steal a phrase from Walt Whitman, ‘I contain multitudes,’ which is how the peacock fan became a metaphor for me in the film.”

Maya spoke about what it was like to embody those multitudes, noting that “Flannery was the harshest critic of Flannery,” and, as a result, “Flannery’s loneliness took over my body even though I was surrounded by people I love. I was changed by pretending to be this person.”

As the Creativity Conversation concluded, the two sets of scholars thanked one another, with Magee noting, “This exchange of information is meaningful to us; we feel part of the work of art you have created.”

Note: “Wildcat” continues its run at the Tara, while the “Crossroads” exhibit is on display at the Woodruff Library through July 12. A video conversation with the curators is available online.

Photos by Andrew Carlin/Oscilloscope.