Natasha Trethewey and Fintan O’Toole somehow made it look easy — enrapturing audiences over three days as they explored the double meaning of “Writing Lives,” the theme of this year’s Ellmann Lectures in Modern Literature.

In addition to writing their own lives — Trethewey in “Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir” and O’Toole in “We Don’t Know Ourselves: A Personal History of Modern Ireland” — they also embody “the writing life,” with careers spent investigating the relationship between art and life as well as between personal and national history.

This marked the first opportunity for President Gregory L. Fenves to welcome the esteemed series to Emory.

“The Ellmann Lectures have brought leading minds in arts, literature and letters to our campus to reflect, inspire and share visionary insights. The Emory community has watched giants and geniuses take to the stage over the years,” Fenves said.

In the words of Carla Freeman, “The lectures offer an even richer experience than the best literary festival. A deep intellectual and artistic momentum builds, and our community comes together over ideas.”

As she introduced the Creativity Conversation on the third day, she noted: “The divisions on college campuses and in the world can make people retreat from public engagement. These lectures remind us of writing’s power to transport and connect us. In addition to celebrating great writers and poets, the Ellmann Lectures forge deep collaborations and genuine friendships that go far beyond these few days.”

Freeman, the Goodrich C. White Professor of Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies, directs the Fox Center for Humanistic Inquiry, the series’ new institutional home.

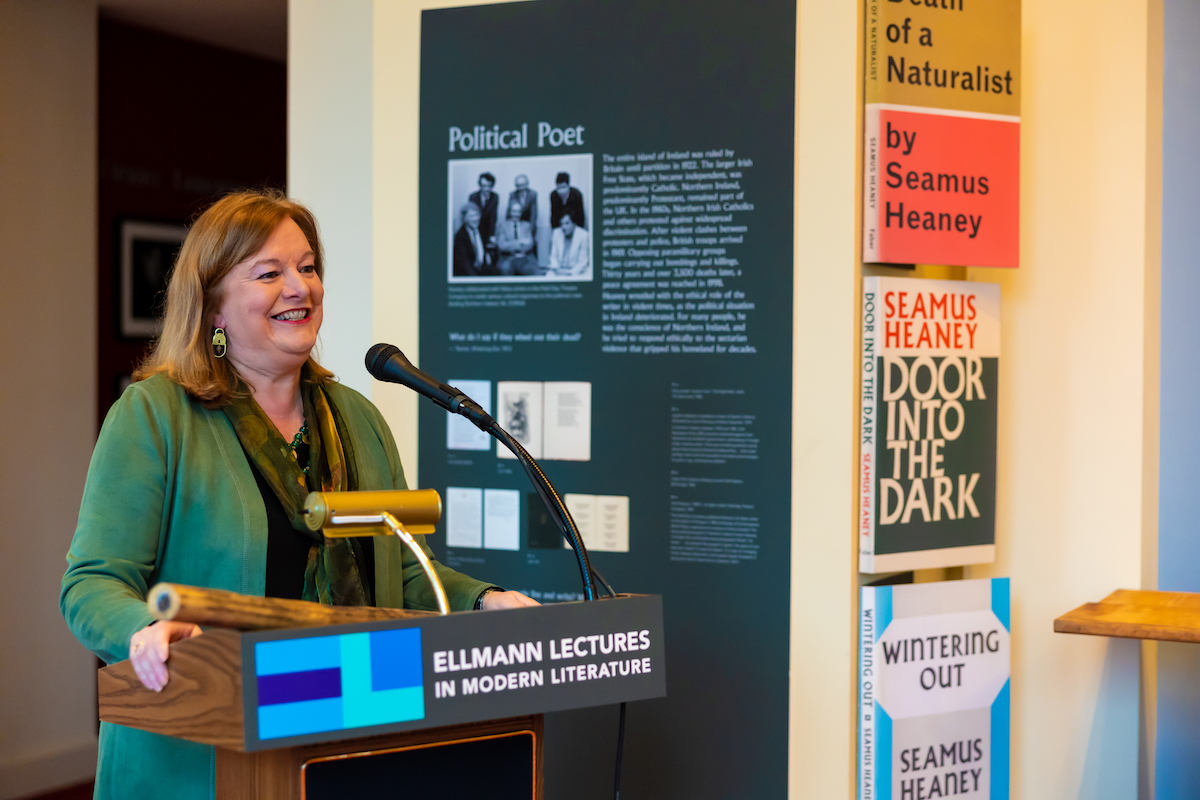

Geraldine Higgins, the series’ faculty director for this and the previous two Ellmann Lectures, got a laugh from the audience on the first afternoon by noting: “Our last Ellmann Lectures took place in 2019 B.C. — Before COVID.” In that time, she acknowledged, the university has welcomed three new classes of students as well as a number of new leaders.

“In conversations with Carla Freeman and the series founder, Professor Emeritus Ron Schuchard, about the importance of these lectures to the humanities at Emory, we knew that we wanted to do something very special for its relaunch,” said Higgins, who is also associate professor of English and directs Emory’s Irish Studies program.

“Recognizing that 2023 marked the 10th anniversary of the death of Nobel Laureate Seamus Heaney, handpicked by Richard Ellmann to be the first lecturer, we wanted to invite two extraordinary speakers with a personal connection to Heaney,” Higgins said.

And, with that, 72 hours of literary bravura followed.

Natasha Trethewey, winner of the Pulitzer Prize in Poetry and former Emory faculty member, gave the talk “The House of Being: Why I Write.”

Day 1: Natasha Trethewey

It’s a safe bet that Trethewey’s Emory homecoming was sweeter still for the affectionate introduction she received from Jericho Brown, Charles Howard Candler Professor of English and Creative Writing and director of Emory’s Creative Writing program.

Trethewey, currently serving as Board of Trustees Professor of English at Northwestern University, was Robert W. Woodruff Professor of English and Creative Writing and directed Emory’s Creative Writing program until 2015.

Trethewey and Brown occupy the rarefied category of “Pulitzer Prize Winner in Poetry” — Trethewey in 2007 for “Native Guard” and Brown in 2020 for “The Tradition” — but they are bound even more tightly as friends and former colleagues.

Pronouncing Trethewey “one of the planet’s greatest writers,” Brown asserted that she “manages the kind of subtle ferocity that works to remedy the disease of historical amnesia,” allowing “her characters and her own history to be as complex as history really is.”

As she began “The House of Being: Why I Write,” which will be released as a book on April 9, Trethewey acknowledged that her lecture “might easily be understood as a riff on Heaney’s ‘The Place of Writing’ [the title of the first Ellmann Lecture]. It is about my relationship to place, my native geography and its history.”

Formative influences

Raised in her grandmother’s shotgun house in Gulfport, Mississippi, at the crossroads of Jefferson Street, honoring the nation’s third president, and Highway 49, a potent symbol for blues musicians, Trethewey reflected on how “the folkways and idioms of the African American vernacular tradition met the received knowledge of Enlightenment thinking and colonial culture, the language of Jefferson.”

Her own birth, on the 100th anniversary of Confederate Memorial Day in 1966, marked a violent crossroads in Mississippi, “a critical moment in which the laws were changing yet the iconic symbol of white supremacy and Black oppression, the Confederate flag, would still be enlisted to send an emphatic message: ‘Know your place,’” said Trethewey.

Her parents’ interracial marriage was illegal in the place of her birth and 20 other states, “rendering me illegitimate in the eyes of the law. Mississippi inflicted my first wound,” Trethewey asserted.

She recalled long walks with her father where he would recite poetry and stories, most of them illustrating some form of the hero’s journey. Her mother imparted a much different lesson, having grown up during Jim Crow segregation. As resistance, Trethewey’s mother would sing “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” each time they passed the Confederate flag.

“My mother was showing me how to signify, how to use received forms to challenge the dominant cultural narrative of our native geography and to transcend it by imagining a reality in which justice was possible,” Trethewey said.

A curious child who was attuned to language early, Trethewey made ample use of the library in her grandmother’s house — a collection that contained the 20 volumes of the World Book Encyclopedia. “Bought the year I was born, the set was meant to be commemorative, marking the beginning of my journey toward knowledge,” Trethewey said.

At the age of nine, Trethewey was determined to read as many encyclopedia entries as possible, believing she could thereby become “worldly.” Encountering the entry “The Races of Man” shook her, with its hierarchical list beginning with the white race at the top while Black people were at the bottom.

“Before that, I had believed in the sanctity of books. What the World Book taught me was only one of many lessons that set me on a path to becoming a writer,” she noted. Trethewey increasingly relied on writing to create order and to preserve her own agency.

After her mother was murdered by her second husband, Trethewey recalled: “It would be several years before the absolute need to articulate the depths of that trauma and the way it connected in my psyche to the legacy of white supremacy … would lead me back to poetry. … In the act of writing, I found that she could be resurrected for a moment.”

Fintan O’Toole is a columnist for the Irish Times and at work on a biography of Seamus Heaney. His talk was on “Crediting Marvels: Experience, Imagination and the Biographer’s Dilemma.”

Day 2: Fintan O’Toole

Before O’Toole took the stage, Geraldine Higgins described him as “the most incisive, witty and insightful observer of Ireland for the past 35 years.”

A longtime columnist with the Irish Times and advising editor of the New York Review of Books, O’Toole is working on the official biography of Seamus Heaney. O’Toole’s memoir, “We Don’t Know Ourselves: A Personal History of Ireland Since 1958,” was named 2021 Book of the Year by the Irish Book Awards and one of the 10 best books of 2022 by the New York Times.

In introducing O’Toole, Caoimhe Ní Chonchúir, consul general of Ireland in Atlanta, observed that “in Ireland, O’Toole is that rarest of beasts, a public intellectual, known by his first name, as in ‘Did you read Fintan today?’ or ‘What is Fintan on about now?’

“Through his column in the Irish Times, Fintan has shaped our national conversation for decades, holding successive governments to account with rigorous impartiality. He has helped democracy to flourish by nourishing citizens’ faith that their voice and their vote counts. That is consequential work,” Ní Chonchúir added.

Honoring the mystery

In “Crediting Marvels: Experience, Imagination and the Biographer’s Dilemma,” O’Toole explored the myriad paths to best summoning the life of Seamus Heaney. Choosing the right one is, he noted, “the biographer’s dilemma.”

He opened with Hamlet’s remonstrance to Guildenstern: “You would play upon me; you would seem to know my stops; you would pluck out the heart of my mystery; you would sound me from my lowest note to the top of my compass.”

As O’Toole observed, “The most important thing about any artist is the alchemical acts that transmute the lead of everyday existence into the gold of pure imagery.” The innate danger, he said, “is that the biographer can become a kind of reverse alchemist, turning gold back into lead.”

Like many Irish writers, Heaney sought not just to render in art what O’Toole refers to as the “accidents” of his own experience but to comment as well on the “accidents” of a nation in turmoil. O’Toole zeroed in on 1972, the worst year of The Troubles — a period of conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted from the late 1960s through the Good Friday Agreement in 1998.

“The accidental, in Belfast in those days, was not sweet happenstance. It was the good or bad luck of being in the right or wrong place at the always wrong time — the moment when the bomb went off or the bullet ricocheted. ‘Accident,’ in that moment of real history, was not an easy idea to embrace,” said O’Toole. “Heaney was trying to find a voice that would compete with the reverberations of the bombs.”

To do so, he physically relocated himself and his family as a personal and artistic strategy. “Heaney was moving away from the immediate manifestations of The Troubles in order to sense that force more clearly,” according to O’Toole.

O’Toole has prior experience wrestling with the life of a great artist, having written a biography of playwright George Bernard Shaw titled “Judging Shaw.” He approached Faber, Heaney’s longtime publisher, and the Heaney family about undertaking the project.

Both parties welcomed him. Matthew Hollis, Faber’s poetry editor, noted: “Seamus Heaney was the head of our poetry household. … We are therefore thrilled that it should be Fintan O’Toole who has agreed to undertake a portrait of this most cherished author. Fintan himself is a writer of principle and distinction and a researcher of tireless fortitude.”

In association with his work on the biography, O’Toole spent time during his Emory visit consulting the Emory Libraries’ Seamus Heaney papers, which were acquired in 2003. “For those who appreciate art, life and their intersection, there is so much that goes on here at Emory of worldwide importance,” said O’Toole.

His goal is even larger than properly celebrating Heaney’s life and artistic legacy. At its best, said O’Toole, “biography doesn’t just tell us about extraordinary lives; it tells us about the extraordinary nature of life itself.”

Introducing the Creativity Conversation, Carla Freeman, Fox Center director, thanked the lecturers for the “prisms their lives cast upon personal and public history, erasure and memorialization, the vernacular and classical traditions.”

Day 3: Creativity Conversation

A well-loved tradition at Emory, new to this year’s Ellmann Lectures, is the Creativity Conversation.

As Freeman defined it, “A conversation is its own form of the creative process — unscripted, impromptu, potentially more emotionally charged, moving in unexpected directions and onto unanticipated terrain.”

Higgins, serving as moderator, asked Trethewey and O’Toole how they settled on the titles of their memoirs. Trethewey credited her former colleague at Emory, Lynna Williams, who passed away in 2017.

“Lynna showed me that, literally and figuratively, the title ‘Memorial Drive’ resonated. My mother was killed and died on Memorial Drive. But also, the desire to remember, to memorialize is the thing that drives me as a writer,” Trethewey noted.

O’Toole laughingly confessed that his main title is “too obscure to be understood outside Ireland.” To say “we don’t know ourselves” in Ireland is, said O’Toole, to exult in “the country’s better fortunes, its rise from earlier being perceived as impoverished and backward.”

More important was the subtitle: “A Personal History of Modern Ireland.” “That is what the writer does — show how one’s own life mirrors, is shaped by and therefore might be a route into larger histories,” he said.

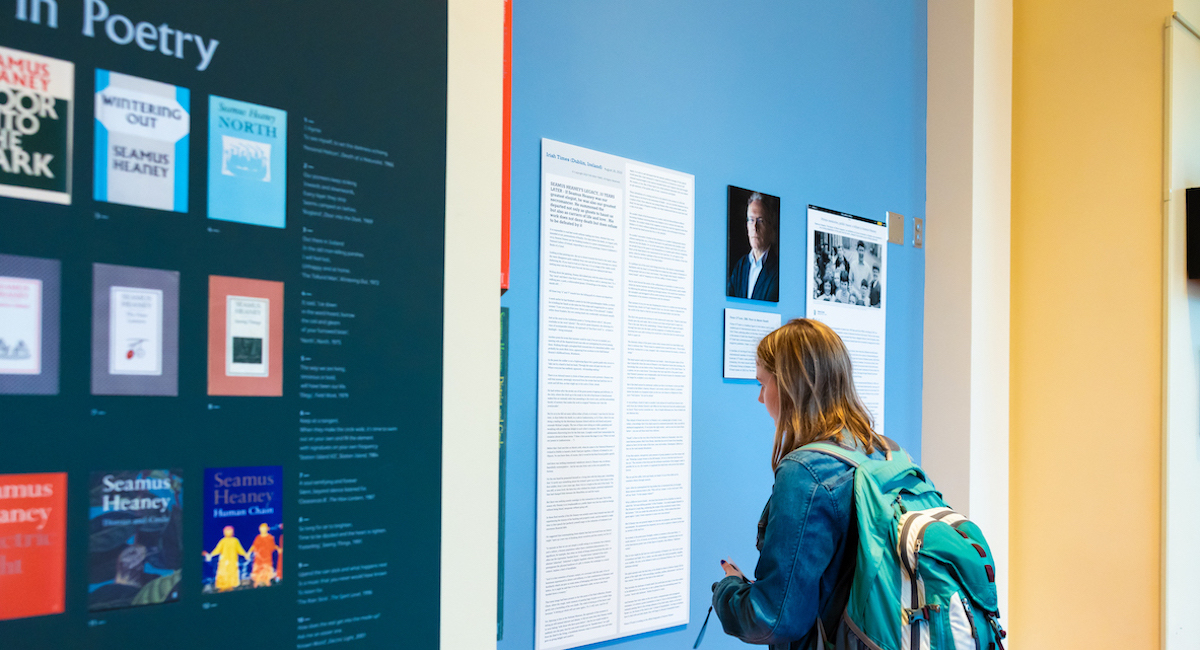

“Seamus Heaney: Listen Now Again” is the traveling version of the acclaimed National Library of Ireland exhibition.

Tackling trauma

Trauma, personal and national, dominated the afternoon’s conversation. O’Toole observed that though Heaney’s life was largely a happy one, he was aware of the stakes for language in Ireland’s ongoing conflict.

“Bad politics is the use of cliché, sloganeering and dehumanizing language that is dead but can also be murderous. Heaney asked himself what good can I do as a poet, and one answer he found was to keep language supple and open, capable of doing what politicians don’t do.

“There needed to be a language that Protestant Unionists could read one way and Catholic Nationalists could read in a slightly different way and feel that they were not being defeated. That’s poetry. In this way, language is not marginal, mere entertainment or obscure; it actually matters,” O’Toole continued.

Trethewey described arriving at her mother’s apartment after her murder and being videotaped by a news team. Watching the footage later that night, she concluded, “The person who went into that apartment is not the same one who came out.”

She pushes back against those who see her life as defined by trauma. Citing the 13th-century poet Rumi, who wrote that “the wound is the place where light enters you,” Trethewey said: “I think about my birth certificate, which says, ‘Mother: colored, Father: Canadian.’ Already that starts to say something and not say something else. For me, it has always been about controlling the narrative.”

The two writers on doubleness

Both Trethewey and O’Toole acknowledged the doubleness at the heart of memoir.

At one point in “Memorial Drive,” Trethewey switches to the second person point of view. The chapter’s first line is, “You remember even though you don’t want to.” And it culminates in a moment in which Trethewey says: “You know, you know, you know. Look at you. Even now, you think you can distance yourself from that girl you were. Write in the second person, as if you weren’t the one to whom any of this happened.”

“In writing a memoir,” O’Toole commented, “you are necessarily two people, needing to go back to the self you were,” and Trethewey added that doubleness is also a condition experienced by Black citizens, as W.E.B. Du Bois observed, as well as women — “until we can subvert the male gaze,” she said.

Each lecturer had something to say about the unreliability of memory. In “Memorial Drive,” Trethewey used court documents as well as the police report and autopsy, blending documentary evidence with her own recollection. And yet, she acknowledged, there were contradictions even in those “official” documents.

O’Toole brings what he calls a “professional skepticism” to biography. He noted, “When writers write about themselves, they are creating art out of their own myth.”

Trethewey interjected, “My father used to say, ‘Tasha remembers everything, whether it happened or not.’”

O’Toole’s ongoing project is the Heaney biography; Trethewey is working on a limited video series for “Memorial Drive” and writing about her father, Eric Trethewey, a fellow poet and teacher who passed away in 2014.

Both authors read poems to close out the Creativity Conversation, with O’Toole reciting Heaney’s “In the Attic.”

From “Monument: Poems New and Selected,” Trethewey read “Imperatives for Carrying on in the Aftermath,” which ends with these lines:

you learned from a Korean poet in Seoul:

that one does not bury the mother’s body

in the ground but in the chest, or—like you—

you carry her corpse on your back.

Through April 14: “Seamus Heaney: Listen Now Again”Curated by Geraldine Higgins, Emory University is hosting the traveling version of the acclaimed National Library of Ireland exhibition. Location: Schwartz Center for Performing Arts, Chace Gallery Hours: Monday-Friday, 9 a.m.-6 p.m. and during public events |