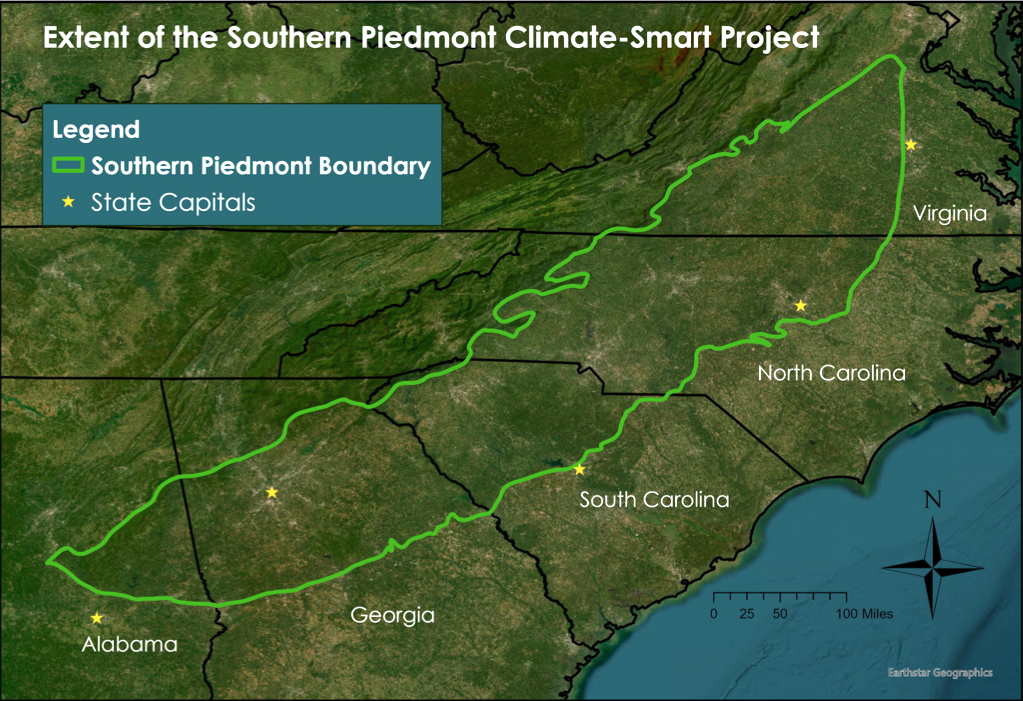

Three Emory University researchers received $5,100,000 as part of a United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) project to help measure and promote climate-smart practices that support small-scale, diversified vegetable farmers in the Southern Piedmont. A plateau below the Appalachian Mountains and above the coastal plain, the Southern Piedmont is a banana-shaped region spanning a bit of eastern Alabama, up across part of northern Georgia and into North and South Carolina and Virginia.

Emory is one of 12 organizations involved in the $25 million project, headed by the Rodale Institute and titled “Quantifying the Potential to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Increase Carbon Sequestration by Growing and Marketing Climate-Smart Commodities in the Southern Piedmont.”

The five-year project is part of the USDA’s Partnerships for Climate-Smart Commodities initiative.

“This effort will increase the competitive advantage of U.S. agriculture both domestically and internationally, build wealth that stays in rural communities and support a diverse range of producers and operation types,” USDA Secretary Tom Vilsack says of the initiative.

The Emory team encompasses three faculty from the Department of Environmental Sciences: Emily Burchfield, Eri Saikawa and Debjani Sihi.

- Burchfield combines spatial-temporal social and environmental data to understand the future of food security in the United States.

- Saikawa is an atmospheric chemist who models global soil nitrous oxide emissions and quantifies soil greenhouse gas fluxes.

- Sihi is an environmental biogeochemist who researches soil organic matter dynamics and greenhouse gas emissions from natural and managed systems.

Boosting food-system resilience

Climate-smart agriculture consists of boosting food-system resilience in the face of future climate threats while reducing greenhouse gas emissions produced by farming. The idea is to find win-win solutions that benefit farmers, consumers and long-term agricultural sustainability.

Much of the climate-smart agriculture funding to date has focused on major commodity crops in the Midwest, including corn, soy, wheat and livestock.

“Our project is unique in that it focuses on the Southern Piedmont and an often underserved piece of our food system, but one that is vital to providing us the nutrients we need — the vegetable sector,” Burchfield says. “We’re also working with the Rodale Institute to include conventional and organic producers.”

The Rodale Institute, founded in 1947 in east Pennsylvania, is a nonprofit dedicated to supporting the regenerative organic agriculture movement through research, farmer training and education.

Input from farmers ‘central’ to the project

About 100 farmers will be recruited through an enhanced incentives program to evaluate the influence of climate-smart agriculture practices on soil health. For comparative data, some of the farms will adopt the practice of using a cover crop, some will continue using conventional techniques while others will employ a no-till technique — or leave the soil undisturbed to better manage soil carbon.

“One of the coolest parts of this project is that farmers are central to the discussion,” Sihi says. “We’re holding workshops to introduce farmers to the plans and to get their input. We want to help build their buffering capacity against the effects of climate change.”

Even as some research in other parts of the country has shown climate-smart benefits of using cover crops, each region is unique in terms of the crops grown, soil types, climate and topography, Sihi explains.

The researchers will monitor and measure how cover crops and no-tillage practices in the Southern Piedmont influence factors such as greenhouse gas and air pollutant emissions, soil health, economic impacts to farmers and any potential social barriers to the use of these practices.

Measuring emissions and soil health

A major piece of Emory’s involvement is the measurement of three greenhouse gas fluxes — or the amount of gases that are both sequestered in the soil and released into the atmosphere — as well as the flux of ammonia, an air pollutant.

“It’s difficult to measure agricultural greenhouse gas fluxes,” she says, “but it’s important that we do so as part of this project. We need to provide farmers and policymakers valid data to help achieve climate-smart agriculture. If we can find ways to benefit farmers and reduce air pollutants and greenhouse gases at the same time that would be phenomenal.”

The towers will stand about three meters high and be equipped with state-of-the-art sensors to measure fluxes of carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide and ammonia.

Sihi will measure carbon content at different soil depths, along with other key physical, chemical and biological soil-health indicators. Adding organic matter to the soil, she notes, can increase the activities of microorganisms that catalyze the process of providing nutrients for growing plants.

She will also develop an algorithm integrating the greenhouse gas and soil data to examine different modeling scenarios for how each may influence the other.

Preparing for the future

Burchfield will focus on whether the cropping regimes explored by the project will remain viable under future climate conditions, including how the suitability of major vegetable crops in the region will shift over the coming decades.

“We’ll also be generating a suite of scenarios estimating the potential change in emissions we might see across the region if more farms adopted the practices we’re exploring,” she says.

The Southern Piedmont comprises nearly 3.7 million acres of agricultural land, and most of the farms in the region are small.

“Many of the folks we will be working with run small family farms and work hard to stay committed to practices that respect the environment,” Burchfield adds. “This requires a tremendous amount of work, and I’m excited that we can play a small part in supporting these innovative farmers.”

The project will also seek to expand markets for climate-smart commodities in the Southeast through partnerships with farmers markets and investigating the best strategies for educating consumers about the value-added benefits of purchasing climate-smart commodities.

Other institutions involved in project include: the Carolina Farm Stewardship Association; Clemson University; the Connect Group LLC; Georgia Organics; North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University; North Carolina State University; the Soil Health Institute; the University of Georgia; the University of Tennessee, Knoxville; the University of Wisconsin, Madison; and the Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

The work is supported by the USDA under agreement number NR233A750004G019.

Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this article are those of the researchers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the USDA. In addition, any reference to specific brands or types of products or services does not constitute or imply an endorsement by the USDA for those products or services.