It’s not often that a body of research begun in 1985 can claim to have a future as bright as its past.

And yet, that is precisely the case for “The Letters of Samuel Beckett” project, the culmination of which was celebrated in high style, with humor and gratitude abounding, in the Jones Room of the Robert W. Woodruff Library on the evening of Sept. 21. For even as attendees looked back, the future beckons as well, with the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library becoming the future home of the project’s materials.

Every type of contributor — former undergraduates and graduate students, a just-named alumni advisory group, librarians, emeritus faculty, staff at the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship (ECDS) and metro-area partners that include theaters as well as the consulates general of Ireland and France — took a well-deserved bow. And no one rushed it, for the community that has grown up around this project is like a small city, as evidenced by the nearly 400 students who have assisted on the project over its life.

Appropriately at the center of the celebration was Lois Overbeck, who — thoughtfully and tirelessly — has been developing the project ever since Samuel Beckett authorized Martha Dow Fehsenfeld as editor and Overbeck as associate editor to locate and transcribe his letters.

‘Cher ami,’ or writing for an audience of one

Kicking off the evening, Lisa Macklin, associate vice provost and university librarian, reflected on the dynamics of letter writing.

“The writer freely gives away the letter to someone else, and a conversation starts. Some might call it a lost art,” Macklin noted, but added: “I know that I have family letters I cherish because they are voices of people who are no longer here with us.”

Beckett knew exactly the path he wanted his letters project to take. He asked his editors to continue the conversation he had started with his correspondents. As Overbeck recounted, “Beckett initiated the most important element of our work, saying: ‘You will get round and see these people, won’t you?’ There was no refusing. That was not a rhetorical question, and of course we would and we did, and it made the difference.”

Fehsenfeld and Overbeck started by consulting archival collections all over the world, and they met with his correspondents in their homes.

“Sometimes,” said Overbeck, “a visit meant to be a couple of hours turned into a couple of days because there was so much to share. The questions we had prepared only scratched the surface. We listened because we didn’t know the whole story.”

The letters begin in 1929; they end in 1989, the year of his death, and “in between are some of the most important years of the 20th century,” Overbeck said. “Beckett knew so many people and was involved in so many ways.”

Ron Schuchard — Emory’s Goodrich C. White Professor of English Literature, emeritus — co-edited three volumes of letters of poet and dramatist W. B. Yeats and had key advice for Overbeck and Fehsenfeld regarding, as Overbeck phrased it, “how much or little to annotate. Ron said, ‘If you are as close as anyone has ever been or will be to what happened, put it all in.’ I’m afraid we did,” Overbeck said.

Riding the wave of digital scholarship

“The Letters of Samuel Beckett” was published in four volumes by Cambridge University Press between 2009 and 2016. Although more than 16,000 letters were consulted and transcribed in the editing process, the selected edition could include only about 2,500 of them.

Thus Overbeck began a productive partnership with ECDS staff, including Sara Palmer, digital text specialist, and Jay Varner, lead software engineer, both of whom attended the event. “They took this digital trove and made it a highly flexible tool for scholarship,” Overbeck noted in thanking them.

The result is Chercher, an interactive index whose two primary search modes are “Letter Data,” which includes those in public archives along with their physical state and location, and “Index,” the people, places and things Beckett mentions in his letters.

“With a book, you are creating something linear,” Overbeck observed. “With a dataset, you can go anywhere and everywhere and make associations. And that is where the discovery comes in.”

Overbeck mused that, “The Beckett Letters project began before most of you were born.” And to that group, she issued an invitation, saying: “If you have a life of scholarship ahead of you, there is plenty to do. Chercher can be the starting point for research in many fields.”

Part of the night’s joy was watching a video featuring alumni, some of whom have gone on to be leading scholars in Beckett studies. The constant among them was acknowledging how deep and valuable their learning was on the project.

Kevin Lucas is the Marion L. Brittain Postdoctoral Fellow at Georgia Institute of Technology, where he teaches in the writing and communication program. He is also an inaugural member of the advisory board that will maintain Chercher by accessing and integrating new materials into the metadata as well as managing project outreach.

As he commented, “So much of academic work was always very individual, building ideas on your own, but this project made me think about things in a different way, about collaboration, about what it is to contribute to a project bigger than you in which you play only a small role.”

Congratulating all who were involved in the project, Jennifer Gunter King, director of the Rose Library, welcomed the arrival of the Beckett materials, which will join the library’s more than 2,200 other collections.

“Archives don’t just happen. As you heard from Lois, they are painstakingly and lovingly understood and established across generations and across time. You have set in motion a resource that, over the next many years, will ensure that Samuel Beckett’s thoughts, relationships and ideas are better contextualized through the collection of his letters,” King said.

Saving the best for last

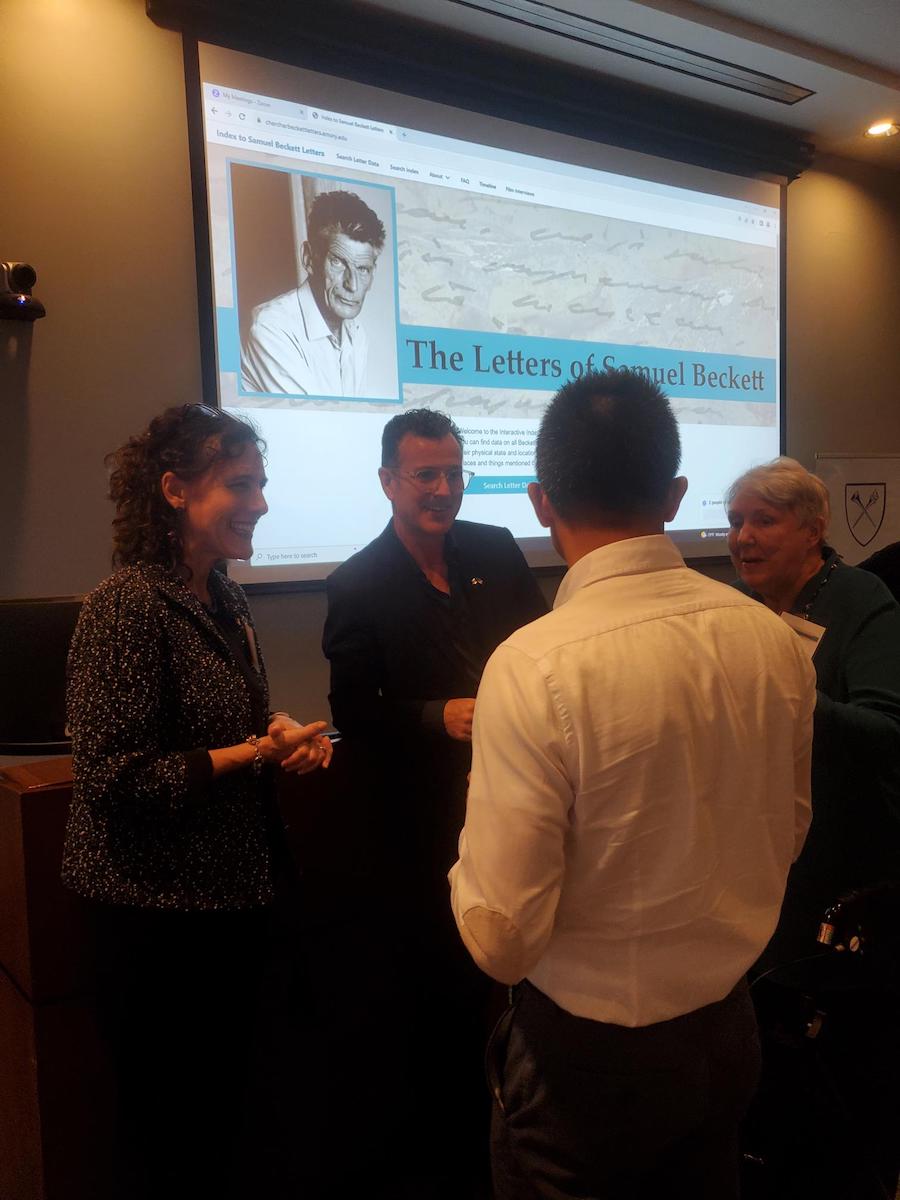

With Beckett himself looking on from the overhead screen, some of the principals from the event on the 21st gather to talk with a guest. (l to r), Jennifer Gunter King, director of the Rose Library; Robert Shaw-Smith, who read as Beckett from letters during the event; and Lois Overbeck, a member of the Emory faculty and one of the original editors named by Beckett to head his letters project.

Photo by Erin Glogowski

The audience was treated to the infamous Swedish television interview of Beckett following his receipt of the Nobel Prize in 1969. His publisher, Jérôme Lindon, sent him a telegram saying, “In spite of everything, they have given you the Nobel Prize — I advise you to go into hiding.” Having dreaded the honor, Beckett responds to his Swedish interlocutor by staring at the camera in stony silence.

But he could be charming and funny. When his favorite director, Alan Schneider, asked who Godot was, Beckett replied, “If I knew, I would have said so in the play.”

As milestones in the project were celebrated at Emory through the years, luminaries such as playwright Edward Albee and author Salman Rushdie — former university distinguished professor at Emory, whose archive is in the Rose Library — read Beckett’s letters to audiences at events. “They were so wonderful that we kept doing it,” said Overbeck.

And so too on this evening, when Brenda Bynum and Robert Shaw-Smith read from the letters. For those who couldn’t be there, a recording captures the many high points.

Here is a small sample of Beckett’s mordant wit in action. When Houghton Mifflin in Boston had Beckett’s manuscript “Murphy” under consideration, the publisher demanded extensive cuts. The road to publisher interest in his work had been rocky to that point for Beckett, who advised his literary agent, George Reavey, to respond for him.

As Shaw-Smith read in the role of Beckett, his Irish accent landing perfectly: “I am anxious for the book to be published and therefore cannot afford to reply with a blank refusal to cut anything. Will you therefore communicate my extreme aversion to removing one-third of my work proceeding from my extreme inability to understand how this can be done and leave a remainder? Be astonished, firm and, up to a point, politely flexible. All at once if you can.”