Emory theology librarian helps lead restoration of African American cemetery

By Susan M. Carini 04G Sept. 7, 2023In the four-plus years that Spencer Roberts has headed the staff responsible for digital initiatives and technologies at Emory’s Pitts Theology Library, he has explored all pathways open to an academic librarian: not only does he support library staff and Candler School of Theology faculty, he also pursues his own research agenda.

Previous digital scholarship projects have found him working with an array of partners, including the David J. Sencer CDC Museum, the Justo & Catherine González Resource Center, Brock University and Georgia State University.

His latest project has gotten him outdoors and well-acquainted with a chain saw as he helps lead efforts to restore and map a forgotten African American section of Penfield Cemetery in Greene County, as well as create an archive for Georgia’s historic rural churches.

Here is how the Penfield story began.

What’s in a name?

Documentary filmmaker Macky Alston grew up in Durham, North Carolina, wondering why so many of his Black classmates shared his last name.

Alston’s forebears were slaveholders, and the families had blended in ways that some members on both sides struggled to acknowledge, as he documented in his 1997 award-winning film “Family Name.”

Delving into his family history did not stop there.

Alston is a descendant of the Baptist pastor, planter and slaveholder Billington Sanders, who served as the first president of Mercer Institute, which was founded in 1833 and became Mercer University in 1837. Also in 1837, the town of Penfield was established to serve the needs of local plantation residents.

Alston, his siblings and cousins inherited the Sanders home. During one visit there in 2019, Alston was invited to meet with a Penfield neighbor and board member of Penfield Cemetery, John Colclough, who said: “I’ve got some stuff to share before I pass out of this life.”

Colclough, who is white, revealed the presence of an African American section of the cemetery that had been walled off, lost to time and the elements.

Alston contacted Mamie Hillman, founder and director of the Greene County African American Museum, and from there a network of universities, nonprofits and community members has mobilized to restore the cemetery, map its gravesites and slowly bring the lives of the residents buried there to light.

Hillman has found more than 30 African American cemeteries near where she grew up in Greene County. She describes the revelation of this forgotten space as “heart-rending,” noting that “the lives of those men, women and children entombed in this cemetery were part of our humanity. They lived and were loved. Sadly, they experienced a demeaning, unjust and racist treatment by their community and its people. Nature did what it does. It reclaimed the sacred space.”

A wall’s legacy of division

Once Mercer University cut a hole in the wall separating the cemetery’s white section from the African American section, the hard work of clearing the space began.

In 1948, for reasons unknown, a wall went up, placed there by the synod of Penfield Baptist Church. “Before then, the cemetery was segregated but contiguous,” Roberts says.

With the wall in place, burials in the Black section were reduced dramatically; the last dated headstone was placed in 1953. Beside a 1973 aerial shot that Roberts includes in the project blog, he notes that “the Black section of the cemetery is indistinguishable from the surrounding forests.”

Roberts first got involved with Penfield as an aspect of support that Pitts provides to Historic Rural Churches of Georgia (HRCG), founded in 2013 by Sonny Seals and George Hart, a 1964 Emory College graduate, to research, document and ultimately preserve historic rural churches across the state.

Penfield Baptist was one such church, and in March 2022 Roberts “tagged along with Seals and others to see where connections could be made. What began as a meeting of a few individuals quickly scaled upward. We discovered that a variety of groups and organizations were working on this one space for a lot of different reasons,” he says.

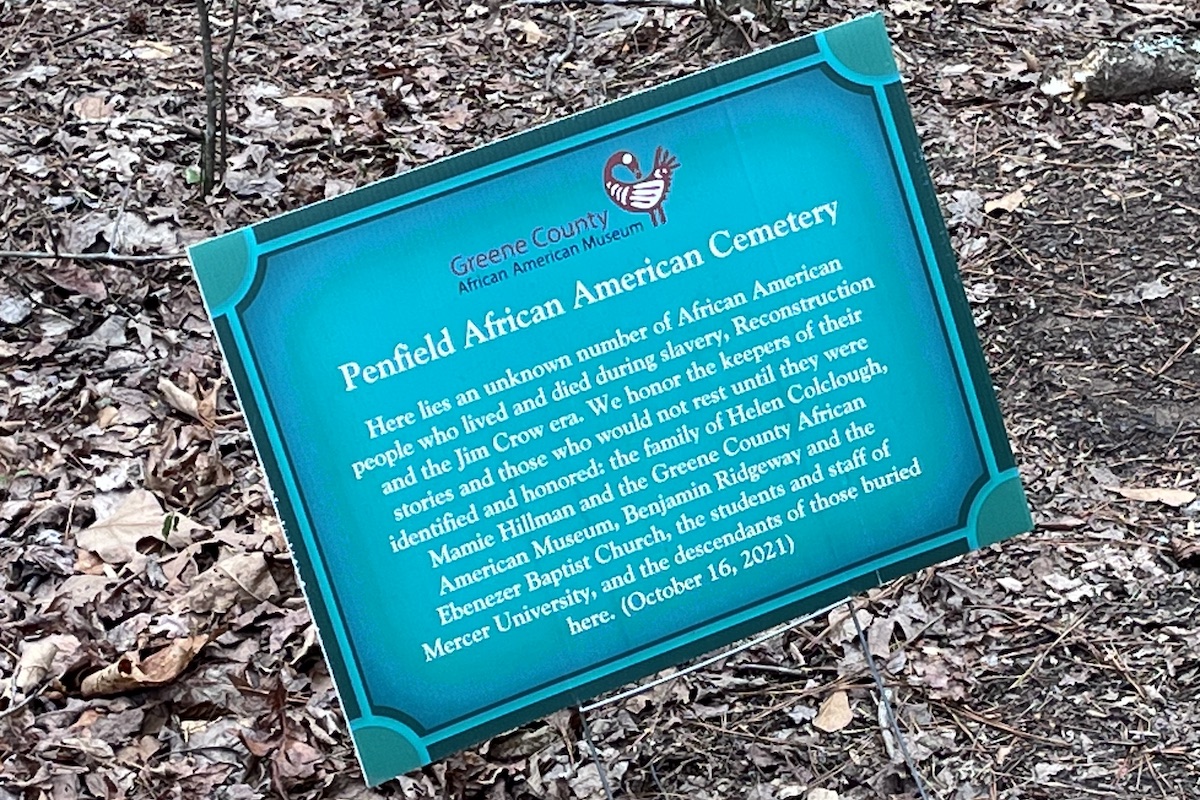

The first of many acts of acknowledgment of those buried in Penfield Cemetery’s African American section.

Its director, Douglas E. Thompson, is also a Mercer history professor. “Mercer began its part in the cemetery project when we joined the Universities Studying Slavery consortium,” Thompson says. Emory became part of the consortium in February 2021.

“Inside the wall, Mercer founders and Penfield residents have been buried. We have uncovered that the brick wall went up in 1948 and that there was a 10-year process to discourage African Americans from entering the section of the cemetery where their loved ones were laid to rest,” Thompson adds.

Mercer owns Penfield’s white cemetery; Fannie Rowe, a descendant of enslaved family members, owns the land in the African American section.

Opening the space — and minds

The first step in restoring the African American section was removing a portion of the brick wall to provide access for community members and volunteers. After Mercer approved creating a passage through the wall, the scope of documenting and restoring the cemetery became dauntingly clear.

Although Mercer's King Center provided funding to survey the cemetery, that work could not begin until someone cleared the fallen trees and limbs laying across gravesites and hiding markers.

Gamely entering territory foreign to most librarians, Roberts borrowed a chain saw.

The cleanup process is painstaking, as no chains or wheelbarrows can be used to haul out the logs once the trees have been cut. The pieces must be carried out to ensure that no further damage occurs to the graves.

Roberts created a Facebook page to coordinate the cleanup days, which have attracted a mix of community members both white and Black, descendants of enslavers and of people who were enslaved.

“When Spencer began organizing Penfield Cemetery cleanup days, Mercer provided volunteers,” says Thompson. “The extent of the cemetery and its importance in Greene County make it necessary to have a large group of cooperating partners to help do this work.”

The clearing is about two-thirds complete, but even as that work continues, Bobby Theberge has played a crucial role as both a scholar and ground-penetrating radar (GPR) expert who has worked for Bigman Geophysical for the past two years. This spring, Theberge completed his master’s in archaeology, with a focus on geophysics, at Georgia State University (GSU); the Penfield Cemetery project is the subject of his thesis.

Funding for the work Theberge is conducting for Bigman Geophysical comes from Mercer’s King Center, GSU and Pitts. The benefits of GPR are that it is a nondestructive, nonintrusive method of using radar pulses to image the subsurface. A company such as Bigman can determine the distribution of burials and boundaries so that nothing is disturbed.

Theberge describes GPR as physically hard, meticulous work carried out by pushing a lawnmower-sized instrument in straight lines very close to one another to create three-dimensional imagery.

“To begin to see burials where there is no surface remnant is very rewarding,” Theberge says. “The transformation will be years in the making, but we have made a good effort so far.”

Penfield grave sites are categorized in four ways: as bearing no marker (which probably will account for 70% of the graves), having uncut field stones, having engraved field stones (most of these burials occurred between 1910 and 1920), or having metal plaques from funeral homes.

Though no one knows for sure while the work is ongoing, Theberge estimates that as many as 1,000 African American grave sites might be in this space. In addition to establishing the distribution and tallying the number of individuals in the African American section, Theberge also can address questions such as the chronology of the sites and groupings of families.

Digitize it — and they will come

Once Theberge’s work is done, a next step may be to investigate funerary records for what they reveal about burials in the section. Having a publicly accessible digital database is key to creating greater awareness and potentially connecting descendants to their loved ones. Roberts will craft that platform, with the goal of featuring storytelling and technology at their best.

Modest about his pivotal roles, Roberts says that the Penfield project has been a “fascinating case study in how a larger network of universities, organizations and community members can unite to effect positive change.”

His colleague, Brady Alan Beard, reference and instruction librarian at Pitts, puts the case more strongly, noting: “The innovation and research eminence on display in this project is second to none, and I hope that the Emory community — and beyond — can learn about the important work that Spencer has done.”

According to Hillman, whose museum site will be a link in the digital chain Roberts creates, “The historical narratives of our communities must be acknowledged, documented, honored, celebrated and preserved. I am grateful to those who — present and future — have a clarity of heart, spirit and mind to embrace this mission.”

The landscape, physical and metaphorical, already has changed substantially.

For instance, each fall incoming Mercer students make what is called “Pilgrimage to Penfield,” which brings them to the university’s original site. Last fall, Alston’s mother spoke candidly with students about the historical record as they visited the Sanders home, and the students learned about the restoration of the African American section from Hillman.

Already, Hillman has been able to bring some descendants to their loved ones’ grave sites, including brothers James and Michael McWhorter who — visibly moved as they stood before their great-grandmother’s grave — reflected, “This person gave us life.”

Alston and co-director Selena Lewis Davidson are at work on the documentary “Acts of Reparation,” which will be out next year. “Framed by national and local events, the film will explore what we each need to do to advance the work of healing and repair,” says Alston. He and Davidson will move across the country in conversation — a journey that began, in part, in Penfield.

“The Penfield project is an excellent example of community-focused work often found at the heart of digital scholarship and libraries. The volunteers involved in the cemetery restoration have been willing to learn new skills, tackle new challenges and put in hours of exhausting effort. I am honored to collaborate with so many dedicated groups and individuals whose unique contributions have made this project a success,” Roberts says.

Unlocking church histories

Evidence of the overgrowth and neglect that came from walling off Penfield Cemetery’s African American section.

President Jimmy Carter contributed a foreword to the book published by the HRCG, “Historic Rural Churches of Georgia.” The dearth of knowledge about Georgia’s historic churches and cemeteries “touched a nerve with him,” says Seals.

Seals describes arriving at “a love of history late in life” after passing through Powelton, Georgia, and stumbling upon the gravesite of his great-grandfather in the cemetery associated with Powelton Methodist Church. He later found out from an aunt that “this is where we came from.”

The partnership between Pitts and the HRCG includes a recent Lettie Pate Evans Foundation grant of $150,000 to create a Historic Rural Church Archive. Led by Roberts, staff from Pitts will produce the digital platform that will combine collections from Pitts, the Jack Tarver Library at Mercer and the John Bulow Campbell Library at Columbia Theological Seminary.

Dedicated work by a host of volunteers, including Spencer Roberts from Pitts Theology Library, cleared the ground, enabling detection of headstones.

“There is nobody else doing exactly what we are doing. I have been so pleased with the respect we are getting. Hopefully, we will spawn similar organizations in other states,” Seals says.

“Our collaboration with the HRCG has provided opportunities to support exciting initiatives with library resources and expertise and to explore innovative solutions for engaging with rural history and communities,” notes Roberts, who adds:

“Both the Penfield project and the Historic Rural Church Archive demonstrate the vast potential found in partnerships among libraries, universities and community organizations.”

Photo credit: Spencer Roberts

Pitts Theology Library Penfield Cemetery Blog Emory joins the Universities Studying Slavery consortium March 24, 2021 Resources

Related Stories