Awash in history, with hearts still tender: A conversation with photographers Jim Alexander and Tom Dorsey

By Susan M. Carini 04G April 13, 2023Jim Alexander recalls climbing a telephone pole to photograph the funeral of Duke Ellington in May 1974, an event that attracted more than 12,000 New Yorkers and featured Ella Fitzgerald singing him home.

For more than three decades, Tom Dorsey was the trusted portraitist of Black families involved in civil rights, business and politics, including Ambassador Andrew Young, Hank Aaron and Marvin Arrington Sr.

In late March, in a program organized by Emory Libraries in partnership with the Michael C. Carlos Museum, they appeared before an audience in the Jones Room of the Woodruff Library primed to hear more about their incomparable experiences as photographers of African American life.

As Valeda F. Dent, vice provost of libraries and museum, said in her opening remarks, having joined Emory less than a year ago: “One of the reasons I was drawn here is because of programming like this, which you will not find anywhere else. We are both honored and blessed to be in the company of these gentlemen.”

The evening of conversation coincided with exhibits at Emory involving both men.

“Creative Justice: A Celebration of Emory’s Arts and Social Justice Fellows Program” honors work that Emory professors and students have done with Atlanta artists since 2020 to foster change. Alexander served as an Arts and Social Justice Fellow in 2021, and one component of the exhibit — on view through May 13, 2023, in the Woodruff Library’s Schatten Gallery, Level 3 — features his photography. Alexander also has placed a large collection of his photographs with the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library.

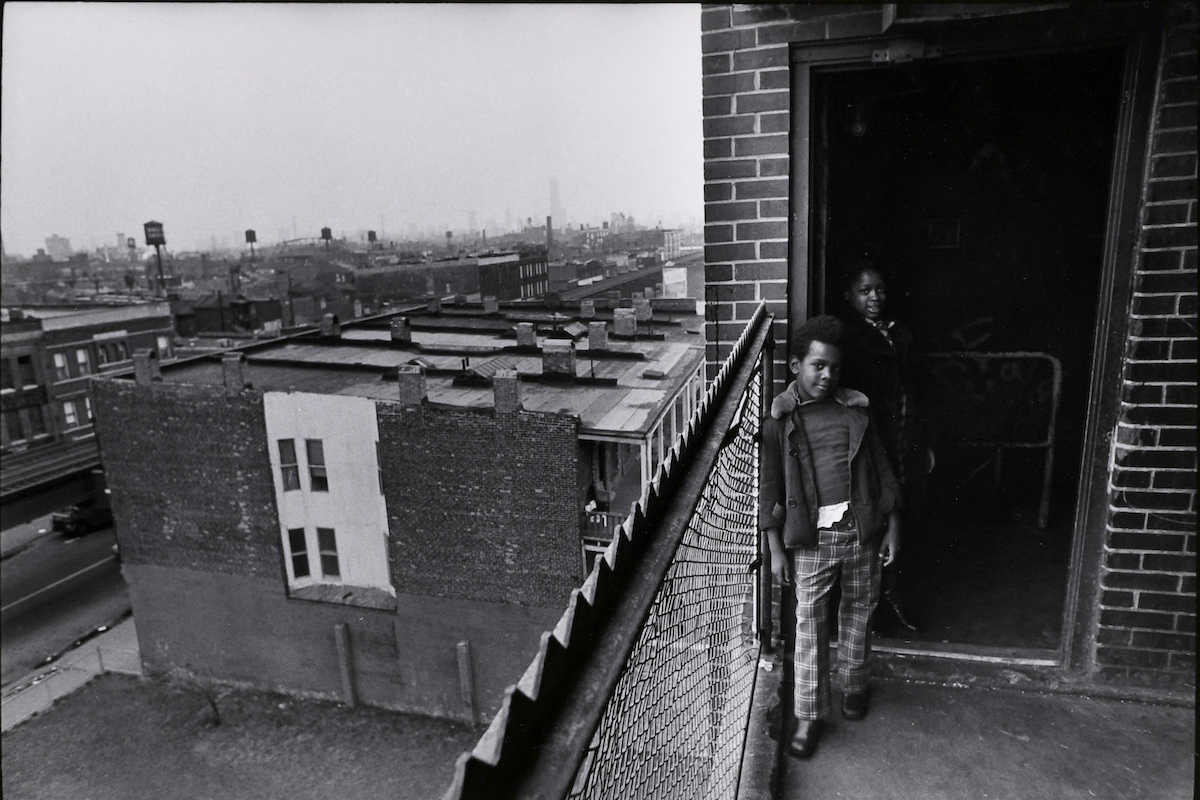

Over at the Carlos Museum is “A Very Incomplete Self-Portrait: Tom Dorsey’s Chicago Portfolio,” which will be on view through July 16, 2023, in the Works on Paper Gallery, Level 1. This portfolio of black-and-white photographs, taken while Dorsey was enrolled at the Art Institute of Chicago, reveals the barren infrastructure of an underserved community and the resilience and stark beauty that can be discovered amid bleak circumstances. In 2022, Dorsey gifted the portfolio to the museum hoping that others might find the images useful.

Carlton Mackey, co-creator/co-director of Emory’s Arts and Social Justice Fellows Program and assistant director of community dialogue and engagement at the High Museum of Art, served as the night’s moderator. He started by letting both men define the main contours of their lives and careers.

Shooting what he wanted to shoot

Jim Alexander picked up a camera — a Kodak “Brownie Hawkeye” won in a game of dice — in 1952, at the age of 17, while in the U.S. Navy. His first exhibit came in 1968 when he graduated from the New York Institute of Photography with a degree in commercial photography. While still in school, Alexander recalls being struck by the falsity of the media’s contention that Black people were “free at last.” It didn’t seem so to him.

To provide a counternarrative, Alexander had the idea of documenting Black life for 10 years. He enjoyed the good fortune of having Gordon Parks as a mentor, whose images focused so powerfully on race relations, the civil rights movement and the African American experience. “Sounds like you got a plan, but your ass is going to starve,” Parks warned him.

Alexander, however, already foresaw that the documentary work would have to be “on the side,” as he termed it, while his living came from teaching photography. That early conversation came full circle when Parks attended Alexander’s “Blues Legacy” exhibit at the first National Black Arts Festival in 1988. Impressed by Alexander’s portfolio, Parks said, “Well, Jim, you ran around and shot what you wanted to shoot.”

Being self-directed in this way has resulted in Alexander’s work being showcased in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History and the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Alexander was honored with the Ebon Dooley Lifetime Achievement Award in 2021.

Reflecting the positive potential of the human spirit

Born in Augusta, Georgia, Tom Dorsey grew up poor on the west side of Chicago. After being knocked out by a brick thrown at someone else when he was in the sixth grade, Dorsey began having memory and attention problems that persist to this day. He dropped out of high school and joined the U.S. Air Force — a move, he says, “that saved my life.”

Dorsey and his wife were involved in music publishing through ABC Records and friendly with major artists such as Curtis Mayfield. Eventually feeling that the music business posed a danger to his family’s values, Dorsey worked for the U.S. Postal Service for more than a decade.

Restless, he then turned back to the creative pursuits that had helped him survive as a bullied young man — the “oddball,” as he described himself, “with a mixed-up mind.” Dorsey earned a degree in fine art from the Art Institute of Chicago and set up an enormously successful business doing portraiture of Black families.

Regarding the philosophy he brought to that work, Dorsey notes: “There are many sides to all people. But the more positive visual self is the only one I try to see with my camera. My photographs reflect the positive potential of the human spirit I saw every time I was given the opportunity to trip the shutter.”

Teach your children well

Alexander is 88, and Dorsey is 85. They have achieved greatness in their own right and been elbow to elbow with it across decades. But for both men, the joy of the night’s conversation was to focus on the next generation.

Dorsey established the mentoring program Brother2Brother in 2006 in partnership with the Atlanta Public Schools. This year, he is mentoring nine Douglass High School Ninth Grade Academy students. Dorsey vows, “I am nothing more than an advocate for the ‘man-teens,’” as he playfully calls the mentees. He adds, “I will help these young men in this way until I am not here anymore.”

Dorsey’s hope is to use his own struggles to inspire others. “Everything that I cussed at and said ‘why me?’ was necessary to get me to this point,” he says.

Mackey responded: “In the midst of all the challenges you faced, you considered yourself worthy of the pursuit of your ideas and dreams. You are giving people permission to do that for themselves. That is a beautiful model of mentorship.”

Alexander, for his part, says: “To do mentorship right, you have to be serious about it.” He works with younger photographers. “I gather them up, and we document something that needs attention from a cultural perspective,” he says. Last year, he took eight photographers to Mississippi to chronicle the achievements of Black blues musicians.

Picking out audience members with whom they had collaborated, Dorsey and Alexander took turns shining a light on their younger collaborators.

Mackey concluded the evening by noting: “The role of the artist is to transfer the longings of people’s hearts. These magicians have given us a vision of ourselves. This has been a chance to literally sit at your feet and learn. We are so grateful.”

| The March 23 conversation was presented in partnership with the Atlanta Preservation Center’s “Phoenix Flies: A Celebration of Atlanta’s Historic Sites,” a program that publicizes Atlanta organizations involved in the preservation, recording and archiving of those efforts. The Rose Library, Pitts Theology Library, Carlos Museum and the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship are among 90 Phoenix Flies partners. |