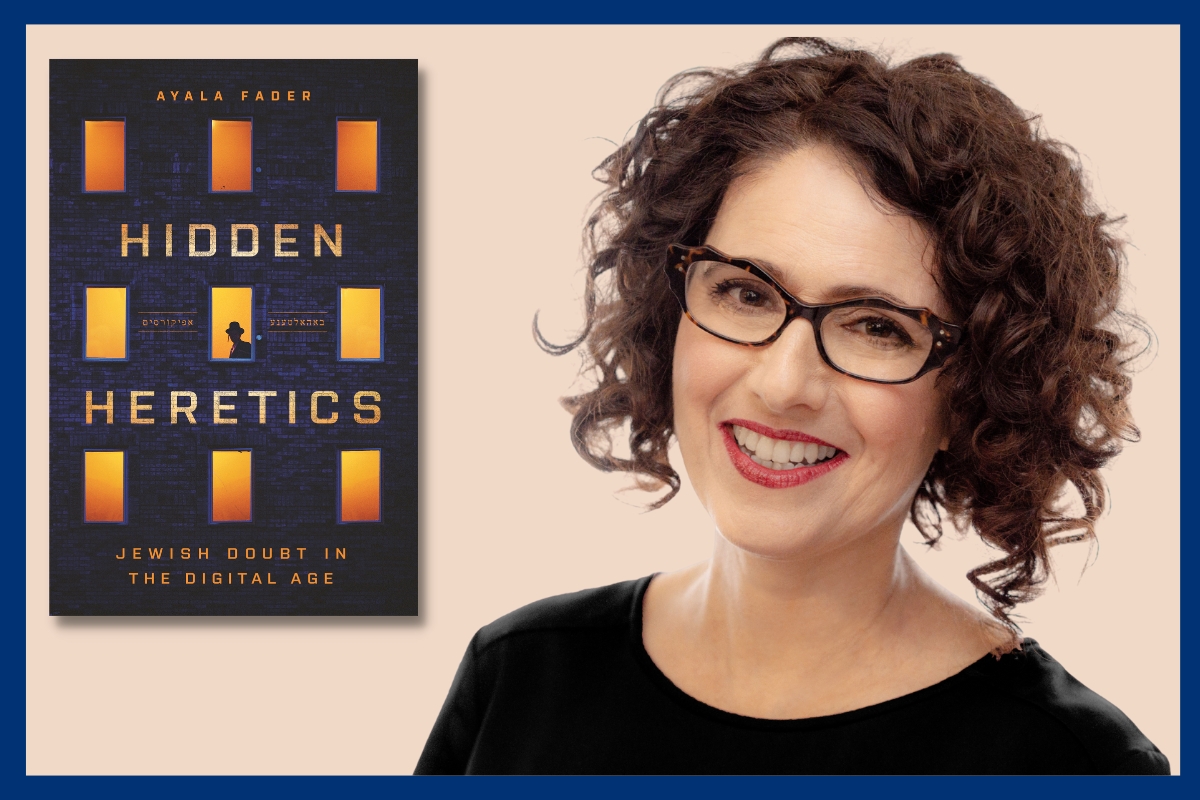

For ultra-Orthodox Jews who question their faith, often with the help of the internet, the experience can be both liberating and devastating — and the effect on their families and communities, says Fordham University professor Ayala Fader, can be “explosive and agonizing.” Fader is the speaker for this year’s Tenenbaum Family Lecture, sponsored by the Tam Institute for Jewish Studies.

In the opening pages of “Hidden Heretics: Jewish Doubt in the Digital Age,” Fader introduces readers to Yisroel, a “double lifer,” and reveals the small details of his appearance that tell the larger story of his crisis of faith.

“He still had his long side curls along with a long beard, thick glasses and a big black velvet yarmulke. However, as a small personal rebellion, he had taken off the big black velvet hat that most Hasidic men wear, and instead of the usual Hasidic men’s long black jacket, he always wore a cardigan or a parka,” she notes.

“Over the next year,” Fader writes, “Yisroel and I met periodically in a wooden booth in the back of a dark bar on Manhattan’s West Side. … He told me how he and his wife were trying to figure out how to make their life together work again. He had promised her that he would keep practicing in front of the children. He hoped it was enough.”

Fader, professor of anthropology, was brought up in New York City in a Reform synagogue where “there was an erasure, perhaps not deliberate, of the past.” She was curious about her great-grandparents, some of whom were Orthodox, and says: “My own history really shaped my attraction to and interest in the topic, which has not ceased to fascinate me.”

Her first foray into this community was “Mitzvah Girls: Bringing Up the Next Generation of Hasidic Jews in Brooklyn,” which was the 2009 winner of the National Jewish Book Award in the Women’s Studies category.

Finding counsel and community amid doubt

Fader makes a distinction between two kinds of doubt.

“The first is doubt that defines or refines faith,” she argues. In this case, the commandments and prohibitions (known as mitsves) are relied upon to keep faith strong despite understandable questions across the life cycle. Fader focuses on “life-changing doubt,” characterized as “the kind of doubt that dramatically troubled a person’s faith in the truth of all they had grown up believing, maybe even obliterating it for good.”

Double lifers not only have used the internet to find one another, an entire support system exists for them that spans the gamut from life coaches and “kallah” (bridal) teachers to professional therapists. Fader admits being initially critical of therapy. “One of the strengths of ethnography, though, is that when something important emerges, you follow the data, and so I talked with therapists,” she says.

She found that “many people, in their efforts to navigate their secrets and changing relationships to their families and Judaism, found therapy critical.” However, in the stories she shares, there is also evidence of harm — for example, when doctor-patient privilege is violated.

Despite Fader’s clear declarations up front about the boundaries of her research role, double lifers often would seek legal advice or emotional solace from her.

In her words, “People were sharing such intimate stories that I found it really challenging. In some ways, however, none of what I experienced is different from any other ethnographic relationship, which is about creating trust. Given people’s vulnerability, I had an obligation to be as transparent as I could be.”

Doubt is gendered

As a result of structural differences in marriage, men and women experience doubt differently. “Women lose a great deal of independence, being expected to stay at home and transfer their allegiances to their husbands,” Fader attests.

For men, it is the exact opposite. After leading highly structured lives in yeshiva — where a day of learning could run from 6 in the morning until 9 at night — men experience “incredible independence” once they marry.

Doubting men are often “devastated when their whole purpose and sense of the world is suddenly removed,” Fader indicates. In many cases, women felt “angry, believing they had sacrificed so much to succeed in their marriages and had been told things that weren’t true to keep them in the home.”

And the people to whom double lifers turn for advice and understanding often react to them based on their gender. For instance, Fader describes rabbis telling men, “You are just too smart or read the wrong thing.” For women, a typical response might be, “You are emotionally unhappy. If your marriage were better, you wouldn’t be experiencing this.”

Extended family and friends can be unforgiving to both men and women, but Fader emphasizes: “It is not because these are terrible people. They think they are saving the children.”

Ban the internet? Good luck

According to Fader, “Technology didn’t create or increase life-changing doubt, but it dramatically changed the way you live it. Now you can explore doubt and meet other people.” If you are brave, that is. There still is a strong determination in the community to limit access.

In 2012, the Mets’ Citi Field was filled to capacity and nearby Arthur Ashe Stadium was rented to accommodate 40,000 ultra-Orthodox Jewish men for an anti-internet rally. Ironically, there are many ultra-Orthodox IT companies, and many men use smartphones for work. As an outcome of the rally, filters blocking the internet were strongly suggested for phones, and schools do require them. Just last year, a rally for women espoused getting off Instagram, which many ultra-Orthodox women use to advertise businesses.

These events notwithstanding, there will never be a complete disavowal of the online world by ultra-Orthodox Jews.

“Rabbis realized that they couldn’t outlaw it. Too many businesses depend on it, and it is too big. Not to mention that there are many ways that internet access and social media support ultra-Orthodox Jewish life,” Fader says.

What would you do?

At the end of the book, Fader describes spending an afternoon with Yisroel’s wife, Rukhy, who asks her to consider what her life would be like if her husband suddenly became religious. Fader writes, “I was not interested in that kind of journey, and he would undoubtedly have to go it alone.” She continues: “Can love be maintained across the divide of what have become different moral world views?”

“Hidden Heretics” was a 2022 finalist for the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature in nonfiction; a 2022 finalist for the Jordan Schnitzer Book Award from the Association of Jewish Studies in social science, anthropology and folklore; and a 2020 finalist for the American Jewish Studies Celebrate 350 Award from the Jewish Book Council.

In the Tenenbaum Family Lecture, Fader has promised to “profile the human stories in a way that goes beyond their Jewishness and that, I hope, resonates with anyone who has dramatically changed who they are with regard to their family or community.”

26th Tenenbaum Family Lecture in Judaic Studies

Ayala Fader speaks on “Hidden Heretics: Jewish Doubt in the Digital Age”

Thursday, March 16, 2023

7:30 p.m.

White Hall, Room 205

The lecture is cosponsored by Candler School of Theology; Emory Center for Ethics; the departments of Anthropology, German Studies and Religion; Graduate Division of Religion; Fox Center for Humanistic Inquiry; Hightower Fund; and Office of Spiritual and Religious Life.