The two faces of Aggretsuko on the course syllabus are the first hints that the Emory College “Cute Studies” course unveiled this spring will include the light and dark sides of the adorable.

For the uninitiated, Aggretsuko is the female personification of a red panda. She smiles simply in her daywear, the blue suit for her job as an “Office Lady” in a Japanese accounting firm. The rage at her mistreatment at work and in her personal life bubbles to the surface in her nighttime iteration, when her face contorts into a snarl as she screams death metal karaoke under heavy eye makeup.

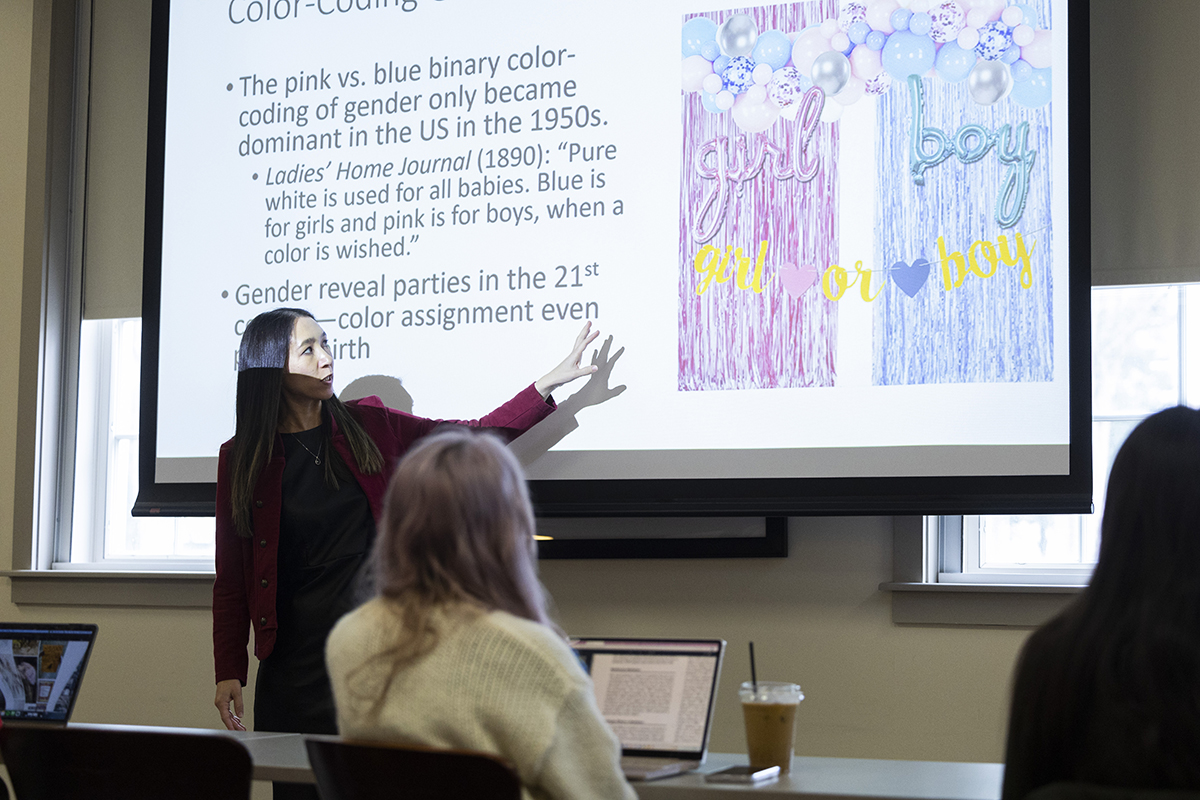

“It’s difficult to think about cuteness without thinking about gender,” says Erica Kanesaka, the assistant English professor who designed the course. “This course is an opportunity to think about that and more, about the politics of race, disability and age at play when cuteness appears in literature and popular culture alike.”

Simon Yu has been fascinated by how rigorously the culture and analysis of kawaii characters can be studied.

As half-Japanese and half-white, Kanesaka has long held mixed emotions about kawaii, especially in American culture. Originally the kawaii characters, tied to an extensive Japanese history of simplicity in art and design, emphasized both softer cultural touchstones in the wake of World War II and pushed against restrictive norms for women.

In the U.S., kawaii has taken on the hyper-feminine, sexualized stereotypes that define a large part of the American vision of Asia in general and Japan in particular. That perception has held even as kawaii diversified into digital spaces and introduced subversive characters like Aggretsuko.

“I have mainly taken STEM classes so far, so I think it’s really fascinating how rigorously this can be studied,” says Simon Yu, a junior with a double major in quantitative science and neuroscience and behavioral biology.

In contrast to some other students, Yu had limited exposure to kawaii characters before the class. He has enjoyed learning both about the culture and analysis, including the project to research and summarize one character in an authoritative “Cute Compendium” encyclopedia that future classes will use and expand.

Students also are conducting complex literary analysis, such as applying the racialization of cuteness to reveal the harm those beauty standards inflict on a young Black girl in “The Bluest Eye,” Toni Morrison’s Nobel Prize-winning classic novel.

Hazel Oh is applying the course framework to her English honors thesis, with Kanesaka as the advisor.

“Describing something as cute is not necessarily a bad thing. But I had never seen the repercussions of it being harmful,” says Alekhya Pidugu, a junior human health and economics major who makes sure to get the calendar that features tubby cat Pusheen every year.

Consideration of the power dynamics revealed some implicit biases that Pidugu, who is applying to medical school this summer, wants to address before becoming a physician.

“I don’t know that I will ever call a person cute again,” she says. “I want to treat my future patients as well as I can, so it is important that I am more cognizant that what I say can help patient health.”

Senior Hazel Oh hoped the class would help her unpack why she felt belittled when people called her cute despite being a fan of Hello Kitty — who was intentionally created without a mouth to keep her own emotions vague — since childhood.

She is now applying the course framework to her English honors thesis, with Kanesaka as the advisor. Her work scrutinizes the memoir “Crying in H Mart” alongside Pucca, a Korean superhuman girl, to articulate the power structures behind a willingness to “self-cuteify,” even while resisting the label from others.

The experience has made her more willing to speak up and interested in pursuing a PhD that allows for deeper study of Asian-American literature and cute studies.

“To be completely honest, I used to be a Hello Kitty myself, more on the quiet side and not taking a stand,” Oh says. “Ironically, I’ve spoken out in class about not speaking out. It has helped me see that cuteness is not an inherent part of me.

“I like that it is so nuanced and an emerging field, because I actually see I can contribute to the ways we study and teach and understand that nuance,” Oh adds.