It was hard work, made more challenging by pandemic restrictions. But when establishing two Georgia Historical Society (GHS) markers crystallizes in a shout-out from Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens and his promise to do more to house Atlantans, it is all worthwhile.

Christina E. Crawford, associate professor of modern and contemporary architecture in Emory College of Arts and Sciences and Masse-Martin NEH Professor of Art History, will remember Oct. 11, 2022, as the culmination of more than five years’ work with her students, university colleagues and community partners to bring overdue recognition to the first federally-funded public housing in the nation: Techwood Homes (for white families) and University Homes (for Black families) — projects that were completed in Atlanta in 1936 and 1937, respectively.

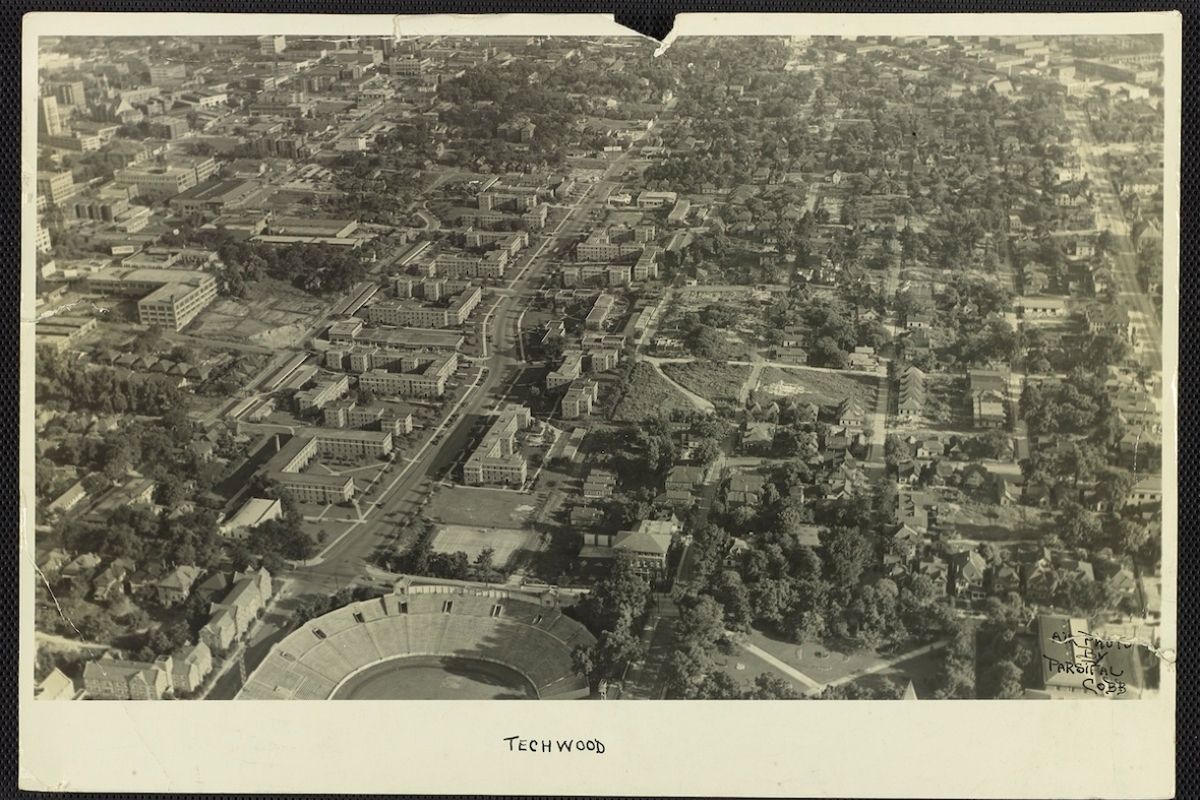

Techwood Homes and University Homes, composed of low-slung brick apartment buildings set in shared green spaces, became models for New Deal housing projects following enactment of the National Housing Acts in the 1930s. Overshadowed by later projects in New York and Chicago, Atlanta’s University Homes and Techwood Homes nonetheless set the aesthetic language and planning logic for American public housing of the mid-20th century. Generations of families lived at both sites for more than 50 years.

Oct. 11 saw two historical markers unveiled — one for each of the two sites, with Mayor Dickens joining the celebration for University Homes. As he stood in front of Roosevelt Hall, which is all that remains from University Homes, the mayor noted: “We started this. The city of Atlanta began what is known as public housing. Soon a reimagined Roosevelt Hall space will be here. Our history does not have to be our destiny; sometimes it might set a path to change our destiny for the better.” Joining him were Atlanta City Council President Doug Shipman 95C and other city leaders, officials from the Atlanta Housing Authority and GHS, and members of Emory Libraries and the Michael C. Carlos Museum.

It was a satisfying conclusion to what began as a pivot project to adjust to research limitations posed by the pandemic. Wanting to shine the spotlight on Atlanta for its part in public housing history, Crawford was one of 10 recipients of Getty/ACLS Postdoctoral Fellowships in the History of Art for 2020-21, chosen for work on the project “Atlanta Housing Interplay: Expanding the Interwar Housing Map.” She also received a research and development grant from the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in Fine Arts and ongoing support from the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship (ECDS).

Courtney Chartier, then-head of research services in the Stuart A. Rose. Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, had suggested before the pandemic that the two housing sites would be well suited to Georgia Historical Society markers. “Though I was intrigued, the process seemed a bit onerous,” says Crawford, “so I set that idea aside.” When research at the scale she hoped to undertake was short-circuited by shuttered archives and travel restrictions, Crawford began to think about the endeavor more seriously as a public history project.

The project’s origin story

Crawford wrote her dissertation on early Soviet architecture and planning, specifically worker housing, and published that research this year in the book “Spatial Revolution: Architecture and Planning in the Early Soviet Union.” When she came to Emory to give her job talk in 2016, she confesses to an awkward moment.

As Crawford presented a map she had created with important public housing projects worldwide from the 1920s and 1930s, a future Emory colleague asked, “Can you plot Atlanta on that map?” “I was totally flatfooted,” says Crawford. “I am well educated in 20th-century housing, and I just had no idea that the first two federally funded housing projects were here. And, when I came to the city, it became clear to me that Atlanta does not get the respect it is due from an architectural history standpoint.”

Resolving to correct the record, Crawford began investigating the Charles Forrest Palmer papers at the Rose Library, gifted to the university in 1969. Influential in shaping Atlanta public housing and then spring-boarding to shape housing policy nationally, Palmer garnered federal funding in 1933 for both “slum clearance” of the Techwood Flats neighborhood and to construct Techwood Homes, one of the first two projects in the U.S. built under the Public Works Administration (PWA). John Hope, president of the Atlanta University Center, simultaneously secured funding from the PWA for the development of University Homes, the other “first.”

As design for those sites began, Palmer traveled to Europe in 1934 and 1936 to investigate already completed public housing projects in Italy, Germany, Austria and even the Soviet Union. Palmer went on to become the first chair of the Atlanta Housing Authority, which he organized, and was also chosen by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to serve as defense housing coordinator for the National Defense Office for Emergency Management during World War II.

Original maps, plans, booklets, photographs and films of European housing sites: all of it was at Crawford’s fingertips through the Palmer papers. “His papers are an absolute goldmine. First of all, he kept everything,” she says. And from her earliest days immersed in the Palmer papers, Crawford had the full support of Emory Libraries to take this further, to illuminate these chapters of city history. Indeed, Rose Library curators Randy Gue, Clint Fluker and the late Pellom McDaniels III mentored graduate students through research in the papers for a “Housing Atlanta” exhibition as part of the Public Humanities Graduate Seminar, taught in 2020 and 2022 by Emory College professors Benjamin Reiss (English), Tom Rogers (history) and Karen Stolley (Hispanic studies) as part of the Mellon-funded Public Humanities Seminar.

For Jennifer Gunter King, director of the Rose Library, “Dr. Crawford and her students’ engagement with the Rose Library’s Charles Palmer Papers and archives at the Atlanta History Center and Atlanta Housing Authority are a wonderful example of how archives, when activated, are transformative resources in our communities. We look forward to welcoming more faculty and students into the Rose Library’s collections and helping them discover research projects that will be equally transformative, on a variety of scales and with a diversity of outcomes — from personal learning to changing the landscape of the city.”

Assembling the team

In 2018, Crawford taught the graduate seminar “Mastering the Archive,” focusing on New Deal Atlanta housing; from that point, she notes, “my students and I were collectively researching the topic.” The first students — Kelsey Fritz, Tosen Nwadei, Courtney Rawlings and William Ulman — wrote research papers that they presented at the 2018 Atlanta Studies Symposium. Crawford taught a second iteration of the seminar in 2022 in which each student wrote an archivally based public history text about Atlanta’s housing past. The students’ articles are available on the Atlanta Housing Interplay website, established in partnership with the ECDS.

Coming from all different disciplines, the students first learned their way around archives in hands-on sessions with Rose Library’s Gabrielle Dudley and Emory Libraries’ Erica Bruchko, and by asking key questions such as “Who makes an archive?” “What is missing from it?” Crawford then sent them out across the city to choose an archive — options included the Atlanta Housing Authority, Sweet Auburn Library and the Atlanta History Center in addition to the Rose Library — to find original materials pertaining to Atlanta’s New Deal housing that sparked their interest.

The unveiling of the Techwood Homes historical marker drew applause from Emory representatives (left: Rose Library Director Jennifer Gunter King; right: Christina Crawford) as well as local leaders, including Atlanta City Council President Doug Shipman 95C (red tie). Sarah Woods/Emory Photo Video

Grateful for what she describes as “my fired-up collaborators,” Crawford credits the high level of student interest to “being in control of their own interests and destiny, and to being grounded in this place where we live. It is rare, at least in art history, to take a class on the place where you are.”

As work progressed, Crawford revisited the notion of applying for historical markers and turned to graduate students Kelsey Fritz (history) and Brooke Luokkala (art history) for help in crafting the application materials.

What can make application for Georgia Historical Society markers “onerous,” in Crawford’s words, is the breadth of materials required when only three to four markers are approved each year based on their cost. Moreover, with more markers already installed in Atlanta than anywhere else in the state, the GHS has “valid concerns about geographical diversity,” says Crawford.

Fritz, who took the first iteration of “Mastering the Archive” in spring 2018, was an Emory doctoral history student at the time with a background in German history. Hence, she leapt at writing about Charles Palmer in an essay on the Atlanta Housing Interplay site titled “Palmer in Berlin.”

Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens (left, closest to marker) was on hand to unveil the historical marker for University Homes, pledging that he is committed to quality, affordable housing for all Atlantans. Sarah Woods/Emory Photo Video

Choosing to earn her master’s degree in history at Emory in 2019 and then enroll elsewhere to pursue a doctorate in public history — a love further cemented by her experience with Crawford’s course — Fritz answered Crawford’s call in 2020 to write the essay on Techwood Homes, which was submitted to the GHS on June 30, 2021. “With no access to archives,” says Fritz, “I drew from public sources as much as I could, including the documentation that had been assembled to place Techwood on the National Register of Historic Places.”

Luokkala is a doctoral student in art history who came to know Crawford in her seminar “Spatial Revolution” on Soviet architecture. Asked by Crawford to write the essay on University Homes, Luokkala visited the Atlanta University Center as soon as it reopened during the pandemic; she and a security guard were the only ones in the archive. Emulating what she calls “the incredible resourcefulness” of Crawford, Luokkala did what was needed to get the University Homes application approved by the GHS. “They needed a fact sheet, which kind of goes against how I think of history, but it turned out to be a good exercise; it helped me streamline for them why this was important,” adds Luokkala.

Both applications were approved on Aug. 27, 2021, with funding for the markers provided by the Rose Library. Then began a further challenge: how to do justice to the history of the two sites in 130 words each? The hope was to emphasize the positive aspects of these sites — their playgrounds, pools, libraries and social programming — while also addressing the uncomfortable history of Jim Crow segregation that the projects embodied.

That back-and-forth with the GHS fell to Crawford, with support from colleagues in Rose Library. Fritz credits her for helping GHS see that “though the two housing projects were connected, they have somewhat separate historic significance. Dr. Crawford was able to convince the Georgia Historical Society that the markers should each have unique information as well as general information about both. The Black community had its own plans for University Homes; it was not just an add-on to Techwood Homes. It was the federal government that tied them together.” Crawford and King were able to acknowledge not only the federal and local leaders who advanced these projects but also the generations of Atlantans who lived at Techwood Homes and University Homes.

Still to come

In addition to the promising turnout on the day of the dedications, local coverage has lifted up the efforts of Crawford and her students. “In the course of this project, I have learned more about Atlanta and its extremely complex institutional landscape, and my students have as well. Writing these applications and organizing these dedications has connected Emory to Atlanta in a way that is extremely productive,” says Crawford.

Though the establishment of the markers was a highwater mark, there are more deliverables on the way for this project. “I started out envisioning this as a digital humanities project. But now I am so invested in it that I will write a book,” says Crawford, who will be on leave in 2023 to do that very thing. She also will be working with the ECDS to move the material from the Atlanta Housing Interplay website to a more customized one that will provide digital mapping and better feature the students’ stories.

Crawford is grateful that the mayor is among her fired-up collaborators. At the ceremony, she returned the favor, noting: “We now have a mayor committed to providing more quality and affordable housing for Atlantans, and so I thank him for his commitment.”

But in Crawford’s view, that responsibility goes beyond his office. As she closed her remarks at the University Homes ceremony, she stressed, “It is the responsibility of all of us to keep up the fight to house all Atlantans.”