To understand the “HOOKED” exhibition at Science Gallery Atlanta is to begin at the end. A giant statue at the gallery exit is covered with shopping bags, vape pens, cell phones, liquor bottles, candy wrappers and other items visitors are invited to leave behind to represent their addictions. The piece, “We’re All Searching for Rest” by sculptor William Massey, represents the relief that many people find themselves looking for externally.

Co-curators Hannah Redler Hawes and Floyd Hall want to destigmatize addiction by showing how the desire to feel better can morph into an uncontrollable habit. The 22 pieces in “HOOKED” are on display through Sept. 4.

“This exhibition is about unpacking all that we think we know about addiction and approaching the topic from a public health perspective,” Hall says. “No one is exempt from struggling with addiction; you just may not have found the right thing yet.”

“HOOKED” is the inaugural exhibition for Science Gallery Atlanta, which opened in May at Pullman Yards. The facility is a part of Emory University’s partnership with Science Gallery International (SGI), a Dublin-based organization that aims to “bring together science, art, technology and design to deliver world-class educational and cultural experiences for young people.” SGI has locations at top universities in Dublin, London, Detroit, Melbourne, Venice, Bengaluru and Rotterdam.

SGI came to Emory through the work of Deborah Bruner, senior vice president of research, and a faculty advisory board consisting of researchers from Emory College of Arts and Sciences, Goizueta Business School, Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing and Emory School of Medicine.

The "HOOKED” exhibition started at Science Gallery London in 2018. The Atlanta version includes work from the London exhibition as well as work by local artists. To infuse the Atlanta flavor, Hall called on some of the city’s most popular public artists to create original displays, sculptures and murals that address addiction.

“I wanted to challenge these popular artists to do something outside of their comfort zone and explore a topic that may not necessarily appear in their work otherwise,” Hall says.

Exploring addiction through art

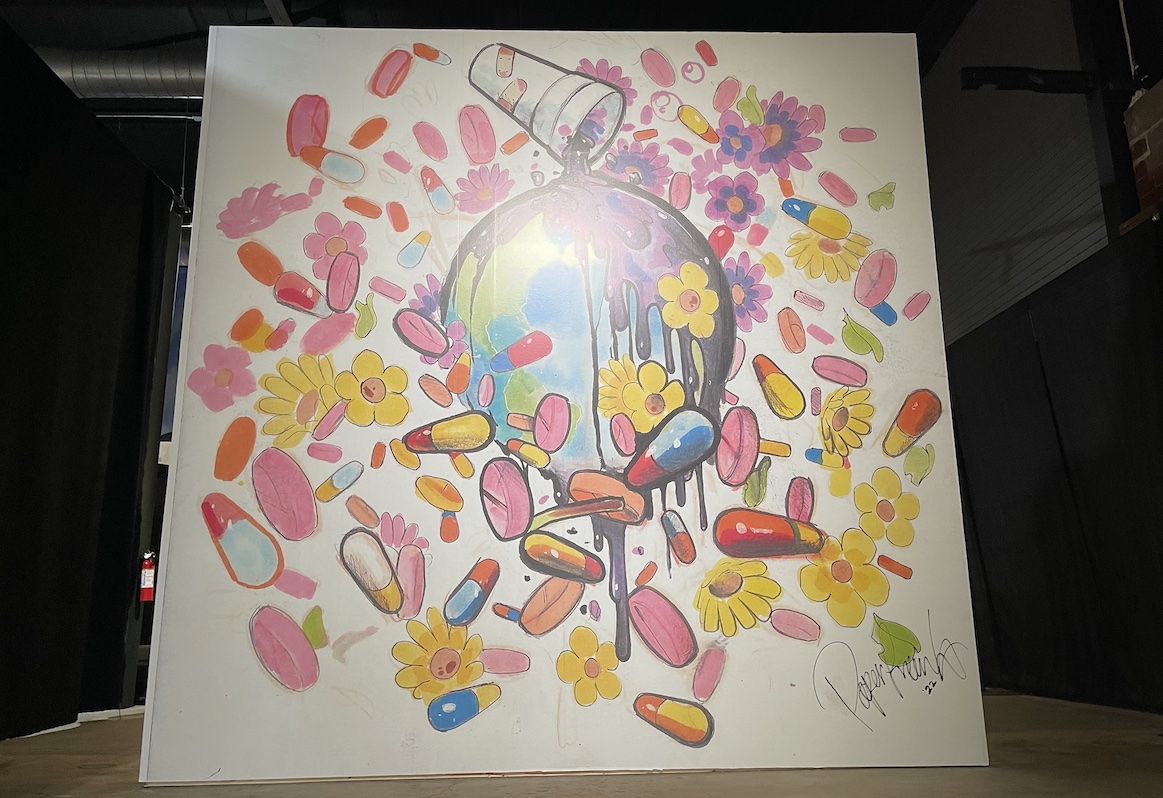

Artist Frank “Paper Frank” Dunson’s design for “Wrld on Drugs,” a 2018 mixtape by rappers Juice Wrld and Future, is at the entrance of the Atlanta exhibition. The marker illustration depicts a cup of lean (purple cough syrup and soda) pouring out onto the earth, which is covered with pills. About a year after the mixtape release, 21-year-old Juice Wrld died from an accidental overdose.

Toward the back of the gallery, Marina Skye, who creates under the name Set by Skye, built a model of the Atlanta skyline out of discarded cardboard boxes. While walking through the large-scale piece, “Trashy City,” visitors hear the beeps of delivery trucks in reverse and Ring doorbells chiming. It’s a comment on the addiction to instant gratification and the cost of that to the environment.

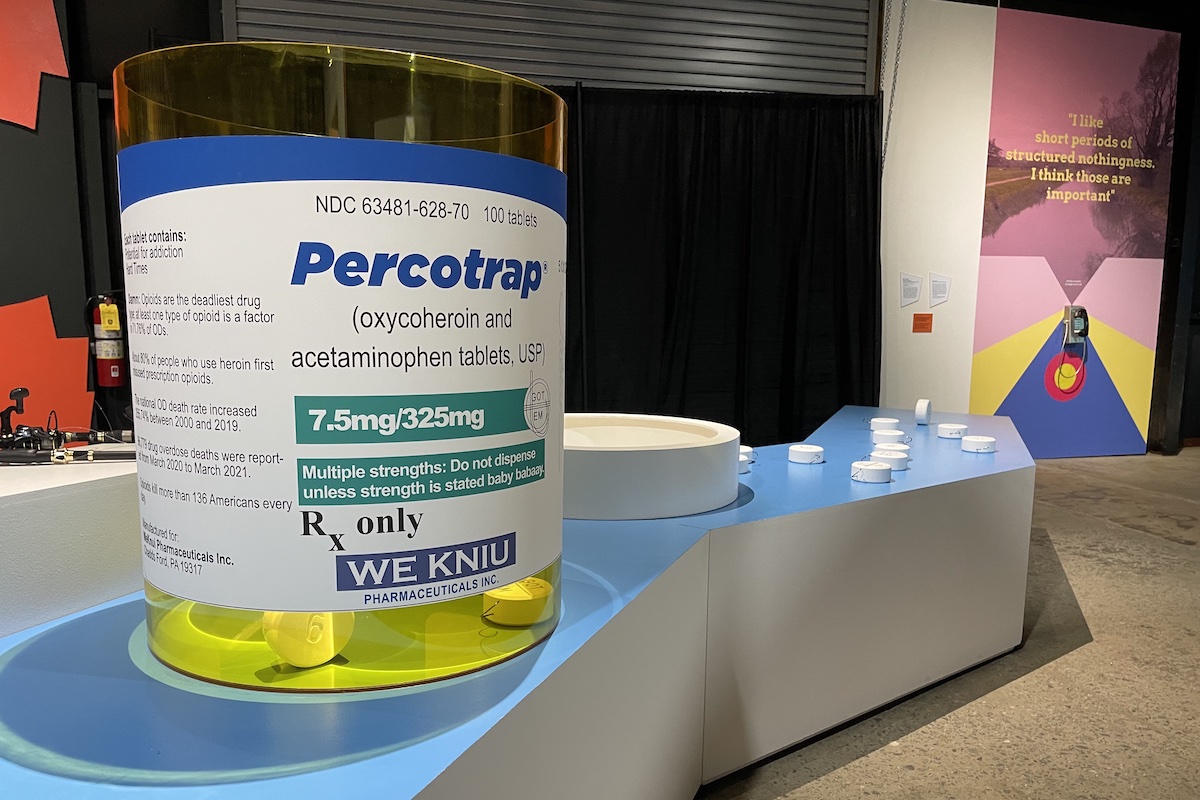

For muralist Fabian Williams, collaborating with Science Gallery Atlanta was a chance to express everything he’d been feeling while following the Purdue Pharma investigation in the headlines. He worked with Mara Schenker, an orthopedic surgeon at Grady Memorial Hospital, and the life care specialists at the Christopher Wolf Crusade to conceptualize a piece that addresses the opioid epidemic.

The result is “Watch for the Hook,” which he designed with local fabricator Antonio Darden. The piece consists of a three-foot-tall pill bottle labeled “Percotrap” with dozens of white pills spilling out onto a blue counter. There are fishhooks coming out of the pills and the words “got ‘em” are etched on one side.

”I talked to a lot of doctors, therapists and counselors to create this piece,” says Williams. “The doctors said in their procedure it’s almost mandatory that they offer a patient opioids for pain, even though we know how addictive they are. I thought doctors had autonomy to give patients options for pain management.”

Williams says he tries to balance light and dark in his work, both literally and figuratively. He’s directing his attention to creating youth-arts programs that inspire kids to imagine the type of world they want to see — one where people matter more than corporations.

“One of the hardest things I had to do as an artist is decide what we want to see,” says Williams. “We get trained to wallow in the misery mud, and we have to clean ourselves off.”

“Staying Alive in Little Five”

More than 20 years of working at a restaurant in Little Five Points inspired postdoctoral fellow Sarah Febres-Cordero to collaborate with illustrator Joseph Karg on a graphic novel about addiction.

As part of her dissertation in the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, Febres-Cordero interviewed dozens of restaurant workers in the neighborhood about their experiences either using illicit drugs or encountering people who use them. She wanted to find a way to educate service-industry workers on how to use Narcan and other first-aid tools to help someone who is experiencing an overdose.

“A lot of me becoming a nurse was wanting to contribute to the community in Little Five Points to address drug use, mental health and homelessness,” says Febres-Cordero. “Most drug users are recreational users, and most overdoses are unintentional.”

The colorful pages in the graphic novel tell the story of a server who sees a customer overdosing on heroin and uses Narcan to help the person until the ambulance comes. One chapter, “Staying Alive in Little Five,” is on display at Science Gallery Atlanta. Karg says that as an illustrator, working on this project made him reexamine his view of addiction.

“A lot of illustrators are trained to make everything look one type of beautiful,” says Karg. “It was a challenge to create something that audiences would respond to but that also reflected the types of people being depicted in a respectful way.”

He also says that working on “Staying Alive in Little Five” made him think more broadly about his interactions with students at Kennesaw State University, where he is an assistant professor of animation and illustration.

“I need to be sensitive to the fact that many college students are recreational drug users, and their family members may use drugs,” says Karg. “I now operate from a position that that may be the case, especially if they are struggling in my class. I ask myself if someone may be going through something.”

Febres-Cordero and Karg hope to be able to tell more stories and finish the novel in the future. Febres-Cordero also wants to include people who have overdosed and been rescued.

“The whole point is to educate people so that fewer people die from overdoses,” she says. “I am a harm reductionist. I am trying to keep people alive and healthy so if one day they’re ready for recovery, they’re alive.”