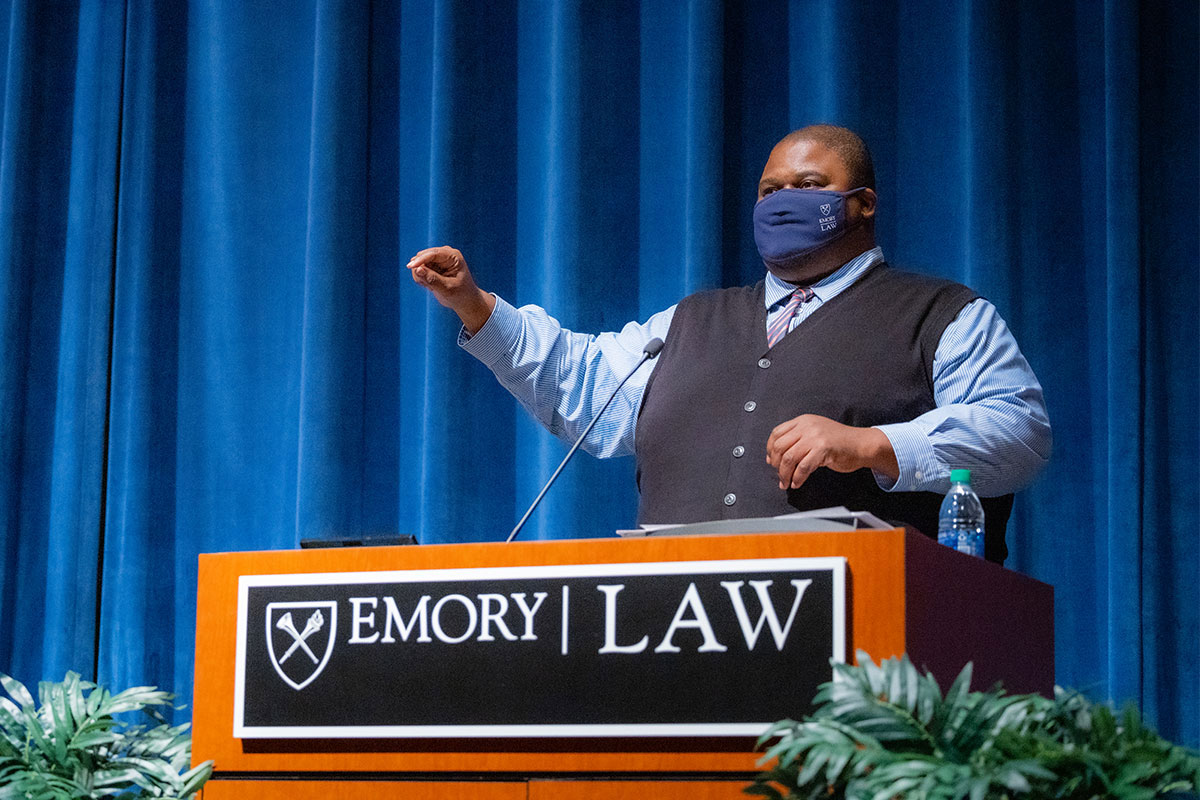

“Martin Luther King Jr. was a critical race theorist before the term existed,” Darren Hutchinson posited in his Feb. 22 lecture titled “Anti-Antiracism: Fighting Backlash, Building Justice.” Hutchinson, a professor of law and the inaugural John Lewis Chair for Civil Rights and Social Justice at Emory University School of Law, delivered a lecture where he discussed landmark civil rights cases, the importance of intersectionality and King’s role in advancing human rights.

The lecture was initially scheduled to be a part of Emory’s King Week celebration but was postponed due to COVID-19. The evening began with a welcome by Emory Law Dean Mary Anne Bobinski and remarks by Emory University President Gregory L. Fenves and Provost Ravi V. Bellamkonda.

"In ways large and small, grappling with racism remains at the center of our national conversation," Fenves said, noting that he "cannot imagine a more important time to be having this conversation or a more distinguished and insightful scholar to lead it."

"Universities were meant for moments like this — to stand in the midst of unfolding history and support the exploration of vital new ideas and challenging paths of inquiry, so that our society can move forward, shaping that history for the benefit of all whom we serve," he continued.

Bellamkonda followed, noting that creating a welcoming and inclusive environment for all students to learn is a top priority. He also encouraged students to find their place in working toward that goal.

“The fight for freedom is a longstanding fight and may be longer still,” Bellamkonda said. “It is the work of generations. It also says that imagination is required. We have imagination in abundance here at Emory. Bring it to the fight against racism.”

Following the killings of Ahmaud Arbery, Rayshard Brooks, George Floyd and Breonna Taylor in 2020, there has been increased demand for more education about the nation’s history with race and ethnicity. Some educators suggested one way to incorporate such teaching is by looking at critical race theory (CRT), which has evoked strong reactions from those who do not wish to see curriculum changes.

Hutchinson started the lecture by defining critical race theory. CRT is a framework that was introduced by legal scholars in the 1980s to examine how people experience the legal system differently based on race. Studying critical race theory includes looking at laws designed to oppress specific groups, such as the Chinese Exclusion Act or court cases such as Plessy v. Ferguson, which reinforced the idea of separate but equal. CRT also looks at how people are penalized differently in the criminal justice system. It is not taught in K-12 classrooms and is rarely taught at the undergraduate level.

After defining CRT, Hutchinson spoke about its foundation: intersectionality. Intersectionality is a term coined by legal scholar Kimberle Crenshaw to provide an analytical framework for understanding how aspects of a person's social and political identities combine to create different modes of discrimination and privilege. This was the crux of his argument about King as a critical race theorist.

Hutchinson quoted King’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail, where he wrote, ‘“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

“King discussed poverty, antisemitism and the plight of the Latinx community — he embraced intersectionality,” Hutchinson said.

Hutchinson also pointed out in his lecture that “as with any movement, there is always a countermovement.” He used Brown v. Board of Education as an example. There was massive resistance to school integration, and some would argue that schools have resegregated. However, with aggressive judicial enforcement, there was a period of progress.

“When the legislation passed, less than 3% of Blacks attended schools with whites in the South, despite the fact that Brown v. Board had been decided 10 years earlier,” Hutchinson said. “In the decade following the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Southern schools became the most integrated in the U.S.”

In addition, Hutchinson provided contemporary examples of movements and counter movements, citing recent anti-protest laws following the 2020 Black Lives Matter demonstrations, new voter ID laws and banning books such as Michelle Alexander’s “The New Jim Crow” from prisons.

Hutchinson is an expert on the 15th Amendment, LGBTQ+ rights and voting rights. In addition to teaching, he leads the Emory University School of Law Center for Civil Rights and Social Justice. The center is made possible by a multimillion-dollar grant by the Southern Company Foundation — the largest single gift to the law school in its history.

Earlier this year, Hutchinson outlined two central goals of the center, which he reiterated at the lecture: placing students in pro bono law and other community groups so they can gain practical experience in civil rights law and partnering with social justice organizations in order to impact policy.

The first goal involves convening policymakers, students, activists, attorneys and academics, while the latter involves exposing students to scholarship on inequality-related issues and equipping faculty to integrate what they learn through the center’s programs into the classroom experience. The center will have a multidisciplinary focus, reflecting the intersectionality Hutchinson spoke of in his lecture.

“You have to be committed and defiant, and you also have to accept that things aren’t going to change in the way you want them to,” Hutchinson concluded. “This is a moment of inspiration despite past failures. There is a tide that has turned.”