A new Emory College of Arts and Sciences effort capitalizes on the diversity of perspectives and knowledge from different fields to help undergraduates develop innovative ideas to tackle a variety of real-world problems.

The Institute for Liberal Arts (ILA) created the Learning through Inclusive Collaboration (LINC) Initiative with additional funding from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. It showcases Emory’s deep commitment to interdisciplinary learning by pairing faculty in different departments who work together to create links between their independent courses.

The goal underscores Emory’s emphasis on liberal arts excellence. Instead of simply disseminating knowledge in a world awash in information, the LINC courses help students spot connections in information and guide how to weigh them.

The program started with four courses this semester, or two LINCs, with six courses (three LINCs) on the spring calendar. Paired classes include differential mathematics with dance, neuroscience and human health, and atmospheric chemistry with German studies.

“We see interdisciplinary study as the core of everything we want to accomplish in undergraduate education,” says Robyn Fivush, Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor of Psychology and director of the ILA. “It provides a much more complete, and sometimes a more complicated, understanding of the world and what we need to do to find solutions to the world’s problems.”

Building inclusivity through interdisciplinary thought

The ILA developed LINC last year with David Lynn, Asa Griggs Candler professor of chemistry and biology, who was drawn to the ILA’s rich history of encouraging intellectual pursuits that cross traditional academic departments.

Lynn had already seen such efforts succeed firsthand. Nearly two decades ago, he used funding as an inaugural Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) professor to create first-year seminars where top Emory graduate students introduced broad scientific concepts by sharing overlap with religion, biology, history, physics, women’s studies and business.

“With the way the social justice and environmental justice movements have evolved, this notion of taking a broader perspective of our world has become even more important,” says Lynn, who used money from an HHMI grant to create the LINC framework.

The issues of PTSD and trauma, for instance, are the focus of both HLTH 385 and PSY 385 this fall. Senior lecturer Chris Eagle’s human health course covers cultural and clinical ideas about trauma from World War I to now, using fiction, poetry, testimonials, theoretical essays and clinical case studies to explore different facets of the traumatic experience.

Senior lecturer Andrew Kazama’s psychology seminar, meanwhile, covers various neurobiological aspects of post-traumatic stress disorder, using peer-reviewed articles drawn from a wide variety of biomedical fields such as genetics, hormones, brain structures and current treatment approaches.

Broadening perspectives

Students focus on their own coursework but meet to discuss shared readings three times this semester. The first joint session followed their reading of a 1917 paper by medical psychologist Charles S. Myers, arguing that “shell shock” in World War I soldiers was the result of physical damage to delicate brain tissue.

Both classes met for a 15-minute overview from Eagle on the history of battle trauma before discussing the evolution of how to consider and treat psychological trauma from physical injuries.

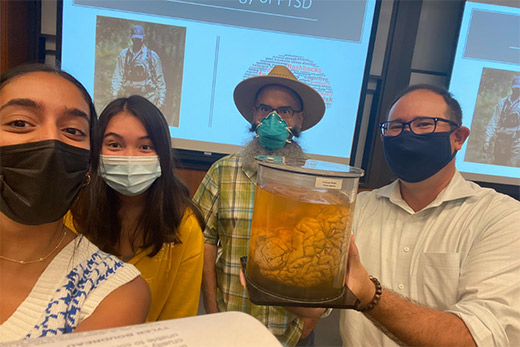

The classes had a similar discussion about the human impact of traumatic injuries following a shared reading of an Iraq War veteran’s suicide letter. In that discussion, Kazama spoke briefly on the possible neurological explanations for what the letter describes, using a brain specimen to illustrate his points.

In their first classes following joint sessions, both professors noted a shift in student interest. Eagle says his students wanted to talk more about the role neural pathways play in how people respond to specific traumas, whereas Kazama’s students expressed curiosity about the meaning of trauma.

“The main takeaway from these LINC sessions has been that what is happening in our brains affects how we experience trauma as much as our cultural ideas of what trauma is,” Eagle says.

As a neuroscience and behavioral biology major, sophomore Kayla Huynh saw Kazama’s course as helpful to both complete her major and for her goal of attending medical school.

The first joint session, though, made Huynh consider the cultural reasons why her parents, childhood Vietnamese refugees after the war, did not consider their experience traumatic.

She is now interested in learning more about the historical and cultural definitions of trauma and is looking for undergraduate research opportunities in childhood trauma, in particular.

“Studying this way has opened up a lot in me,” Huynh says. “It’s something Emory does extraordinarily well, finding these connections between disciplines so we can learn to appreciate different perspectives. It’s so valuable to see what you can learn when people can pull in information from their own backgrounds and respective majors.”

Creating more LINCs

Fivush, along with Lynn and ILA senior lecturer Kim Loudermilk, plan to apply for more HHMI funding to expand the program.

The trio and a LINC committee made up of faculty from across Emory College also plan to continue with additional paired courses next year. The ILA plans workshops for faculty to consider creative ways to bridge their work with other departments.

Kazama, who sits on the LINC committee, says the critical work is helping professors and students alike to think about a topic that will resonate differently in other fields.

“The way I explain it to my class is we are learning to distinguish between revealed truths and observable truths,” he says. “Science is observable truths, while revealed truths come from religion, philosophy and the humanities.

“Neither is more true than the other, because both are incomplete truths of our universe,” Kazama adds. “I can talk all day about how everything you do is the result of your neurons firing or not firing, but that is not the entire truth. You need both.”