Early career scientists at Emory and Georgia Tech had a stressful year, even after pandemic-related restrictions on laboratory research eased. Over the last several months, graduate students and postdocs have been participating in a virtual pilot program aimed at mental health and wellness concerns.

Sponsored by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the program was called “Becoming a Resilient Scientist.” Lasting from January to May, the program consisted of six webinars, each followed by a small group discussion. Topics were tailored for scientists and included emotional intelligence, cognitive distortions and imposter fears, developing assertiveness and resilience when getting feedback or criticism, and developing better relationship with mentors.

At Emory, the program had twice as many applicants as available spots for the small group discussion (40 versus 20), so organizers had to hold a lottery to select who could participate.

Now Laney Graduate School and the School of Medicine’s Office of Postdoctoral Education have confirmed that they will hold the program again in the fall, this time face-to-face.

“This kind of programming is something we should be doing regularly,” says Rob Pearson, assistant dean for professional development and career planning at Laney Graduate School. “These skills are important under any circumstance.”

Students and postdocs reported that they gained insights and tools from the webinars, but the small groups discussions really held them together.

“This program came at the ideal time for me,” says Lauren Liebman, a third year graduate student in the Biomedical Engineering program at Georgia Tech and Emory. “The discussion groups were a great way to connect with people having similar experiences and similar challenges.”

Liebman’s research had been in its most uncertain state in the last year, and she’s had to reorient topics and proposals. When Emory and Georgia Tech shut down non-COVID-related research last summer, she had to spend about 3 months away from the lab. Together with advisor Brandon Dixon at Georgia Tech, she is now planning a project on lymphedema, the damage to lymph nodes that is a common complication of cancer treatment.

Going through the Resilient Scientist program encouraged Liebman to begin wellness coaching at Emory and to start therapy off-campus, she says. It also encouraged her to discuss the topic with her classmates and co-workers.

“We’ve had more communication about wellness and mental health in the last few months than in the previous few years,” Liebman says.

Self-imposed and external pressure

Early-career scientists spend long hours working in the lab, squeezing in the writing of grant applications and research papers. Nationwide, they face a culture in biomedical research that imposes both external and self-imposed pressure. Research has found the incidence of depression and anxiety in graduate students are more than six times the rate observed in the general population.

An effort to mitigate these pressures, the Resilient Scientist program was designed by Sharon Milgram, director of NIH’s Office of Intramural Training and Education and an alumna of Laney Graduate School. The National Institutes of Health had an enthusiastic response to the program; some 50 universities across the country, including Georgia Tech and Vanderbilt, took part as well.

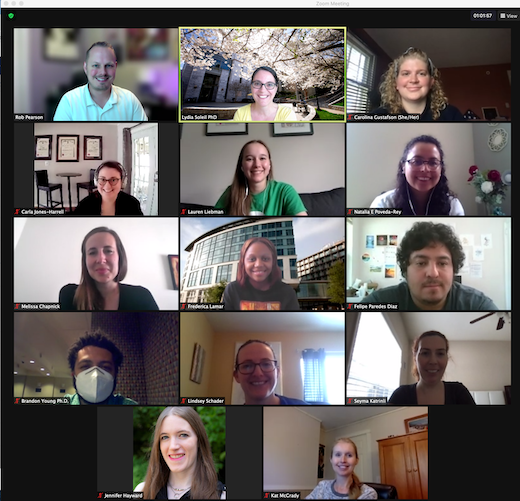

At Emory, the small group included postdocs from the Departments of Chemistry and Biology and the School of Medicine, along with students from Laney Graduate School. The discussions were facilitated by Pearson and Lydia Soleil, director of career development in Emory’s Office of Postdoctoral Education.

“Our job was not to say too much,” Soleil says. “It was to create a space for camaraderie, where students and postdocs could learn from each other.”

Soleil and Pearson went through 14 hours training specifically for the discussion facilitators, taught by therapists contracted to NIH. A therapist mentor also attended each group discussion and gave feedback to Soleil and Pearson immediately after each meeting.

“I was impressed about how all of the participants supported one another,” Pearson says. “I would frequently hear, ‘What you said resonated with me.’”

Program participants say that they gained insights and tools from the webinars and discussions that they have used to both be more productive and balance their lives.

“The big reason why I wanted to take this course was to figure out better tools for myself, to stay motivated and on track,” says Brandon Young, a FIRST (Fellowships in Research and Science Teaching) postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Biochemistry.

Young started at Emory in Bo Liang’s laboratory in September, after earning his doctorate at Medical University of South Carolina, so his work was never interrupted by pandemic restrictions.

Young wanted to take full advantage of his time during the pandemic, and found that he was pushing himself so hard that he sometimes didn’t have time for maintenance tasks such as laundry. “It seemed like I was always working on something, yet still didn’t have time for day-to-day things,” he says.

Taking suggestions from fellow program participants, Young began journaling and found a weekly task list helpful.

“It’s not a ‘must do’ list, but more of a priority list,” he says. “It became a guideline so that I don’t get overwhelmed with how much is on my plate.”

After completing the Resilient Scientist program, Soleil and Pearson are planning a face-to-face reunion for participants this fall.

“I would love to meet everyone in person,” Liebman says.